SMASHUPTOO

You may ask yourself, “why construct a design studio around a pretty Gothic ruin on a hill above a sleepy town halfway between Venice and Vienna?”

And you may ask yourself, "How do I work this?"[1]

[1] Extract from "Once in a Lifetime" by Talking Heads, produced and cowritten by Brian Eno, released February 2, 1981, through Sire Records. David Byrne's lyrics and vocals were inspired by preachers delivering sermons.

CMT

Michelle Howard

Luciano Parodi

STUDENTS

Julian Berger—Ode to a Ruin

Paul Böhm—Head in the Clouds

Daron Chiu—Ruinen Lust

Lauren Marchand— From the Ground Up

Prima Mathawabhan – Symbiotic Garden

Alina Meyer—Coalesce

REVIEWERS AND SUPPORTERS:

Michel Hirschbichler – Architect, Guest Prof. IKA, Acad. of Fine Arts Vienna

Renate Jernej – Historian and archeologist, Verein HistArc, Carinthia

Gertrud Pollak – MA, Verein HistArc, Carinthia

Elke Krasny – Head of the Depart. of Education in the Arts, Acad. of Fine Arts Vienna

Elke Knoess-Grillitsch – Peanutz Architects, Berlin

Ryan Stec – Artist, producer and designer, Ottawa

Josef Pepper – Former Vice-Mayor, Friesach

Mag. Lic. Leszek Zagorowski, – Propst Dechant, Friesach

2020 and 2021 have been years of collisions. The ongoing global pandemic[1] forced change on any activities involving contact with other humans especially interactions and collisions with our respective communities. Amid this situation and inspired by the practices and achievements of early gothic builders we questioned what the value of these interactions and collisions in architecture might be. We baptised this yearlong research and design project, SMASHUP[2] and SMASHUPTOO respectively. SMASHUPTOO focused on the community of Friesach, a pretty medieval town halfway between Vienna and Venice, and proposed new possibilities for collisions and interactions through proposals for the maintenance, repair and regeneration of the remains of a Gothic ensemble on one of the hills which surround it.

In the Middle Ages, gothic churches were intimately connected to the place in which they dwelled. Contrary to other edifices, they were often paid for, built and maintained by the community. Indeed they were frequently big enough to house every one of the towns citizens. These dwellings in which all can shelter, thrive in tandem with their communities because they are the products of a shared ambition and civic pride. To start from scratch on virgin ground would have seemed a curious undertaking. Existing buildings provided not only valuable building materials but also knowledge of preceding ideas and building techniques, and a notion of site. Stone fountains of knowledge. The act of construction was considered part of a process of continuous maintenance and, the resulting building was considered completed, not closed, because the only constant in early Gothic constructions is that, until modern times, they have continually been expanded, refurbished and rebuilt. Only with the advent of the 18th century and more intensely with the onset of Modernism has there been any discussion about a desire to return any of these buildings to their original state. Indeed the discussions around the reconstruction of Notre Dame in Paris show just how difficult it would be to choose just one “original” state.

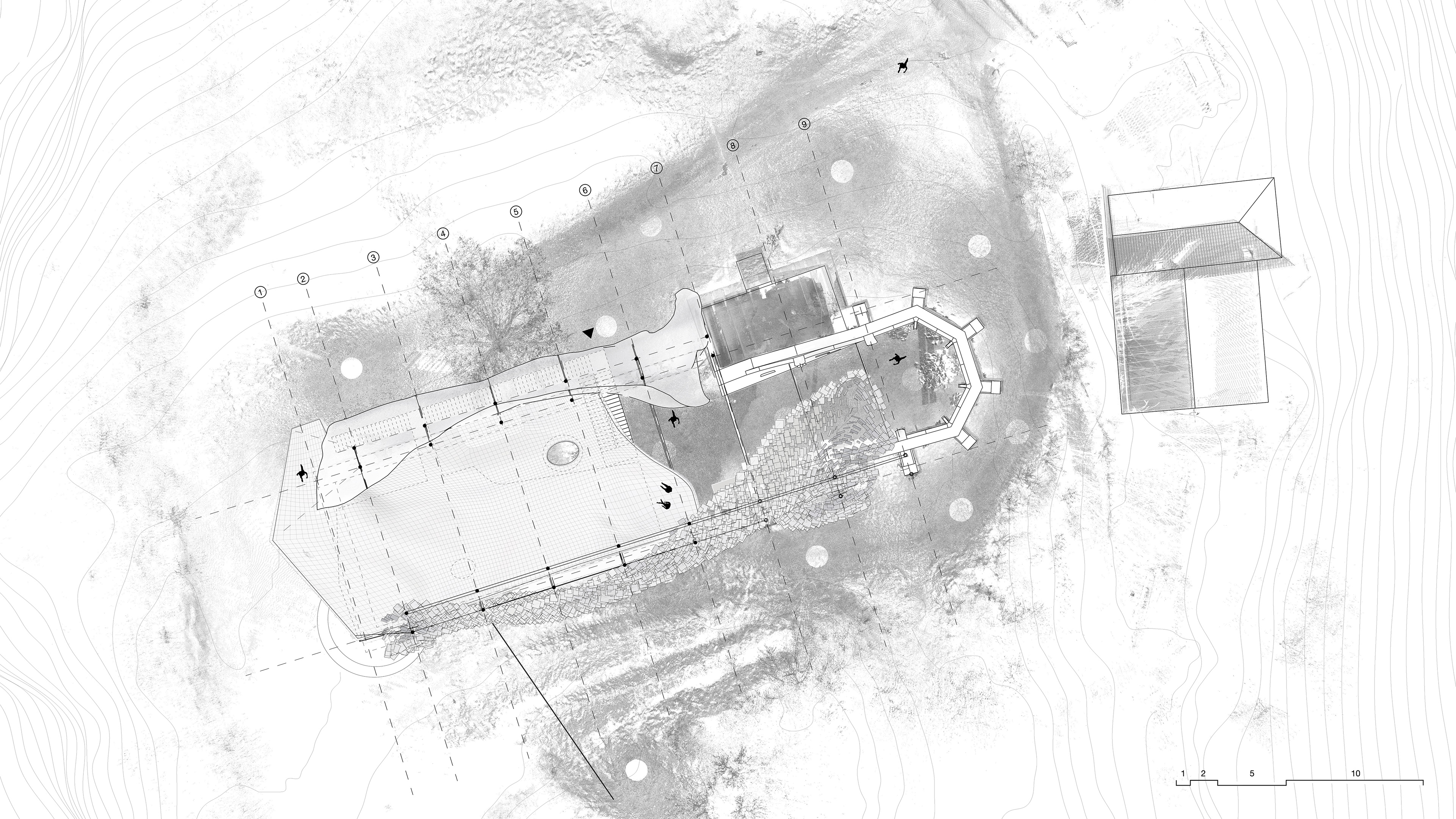

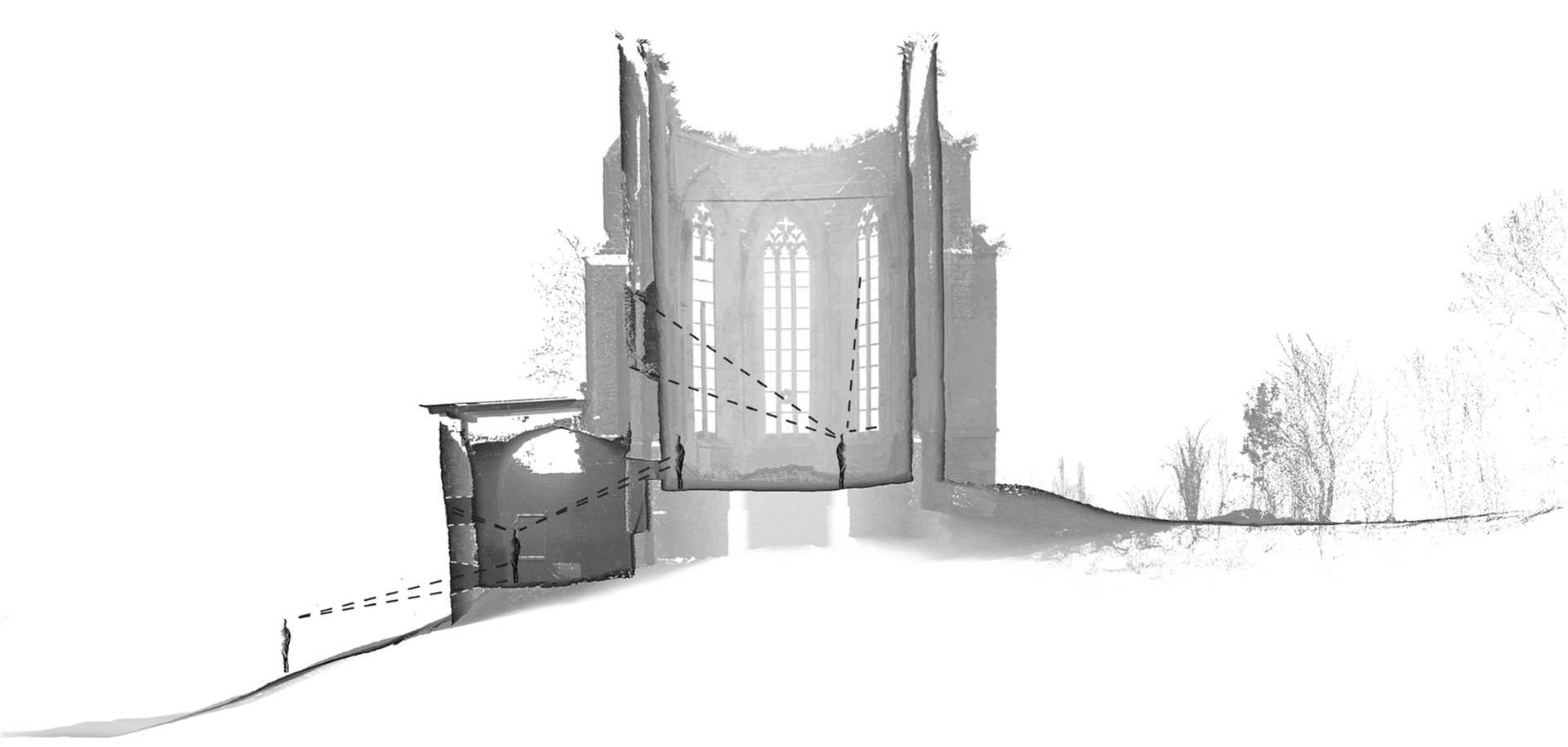

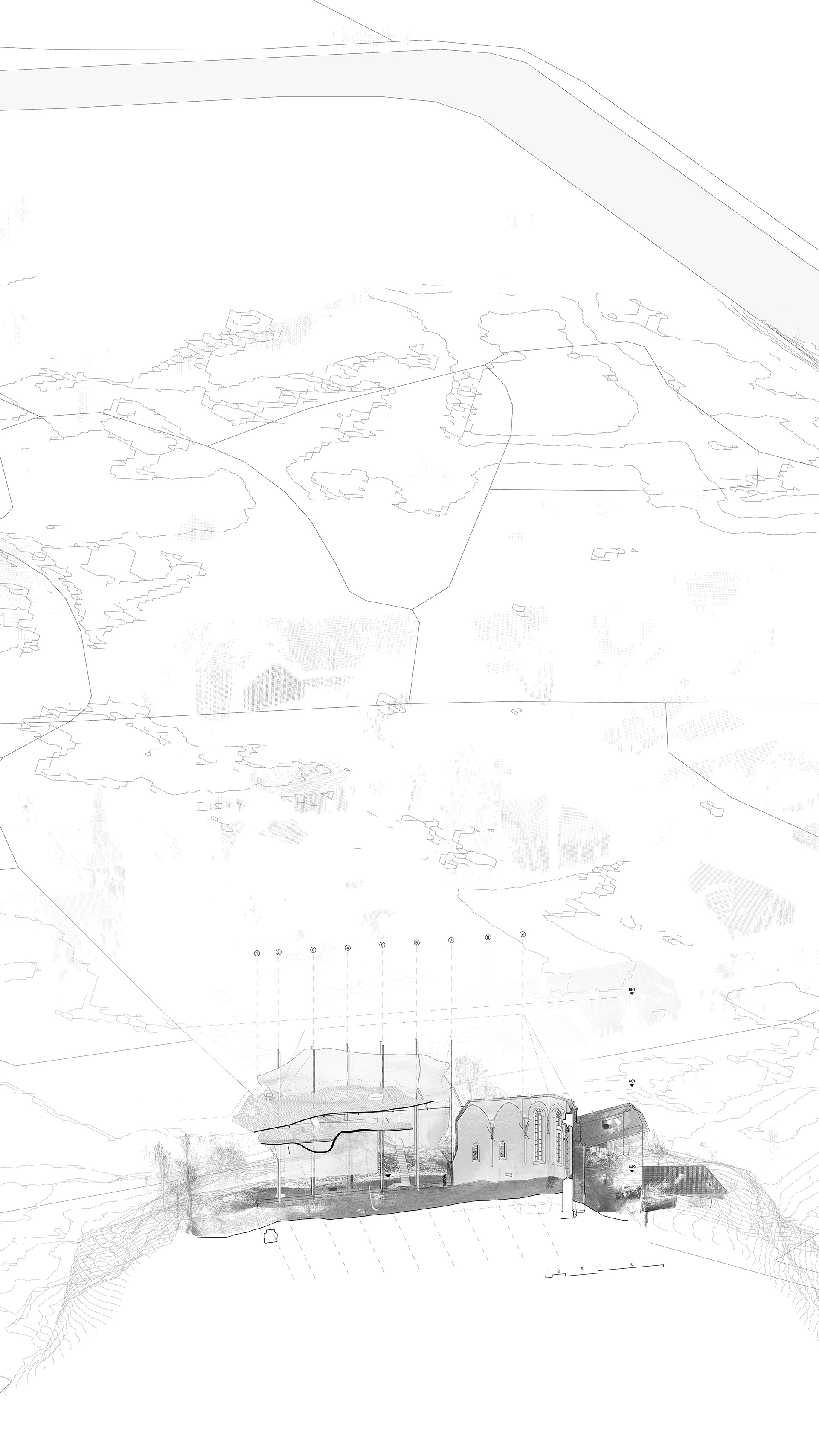

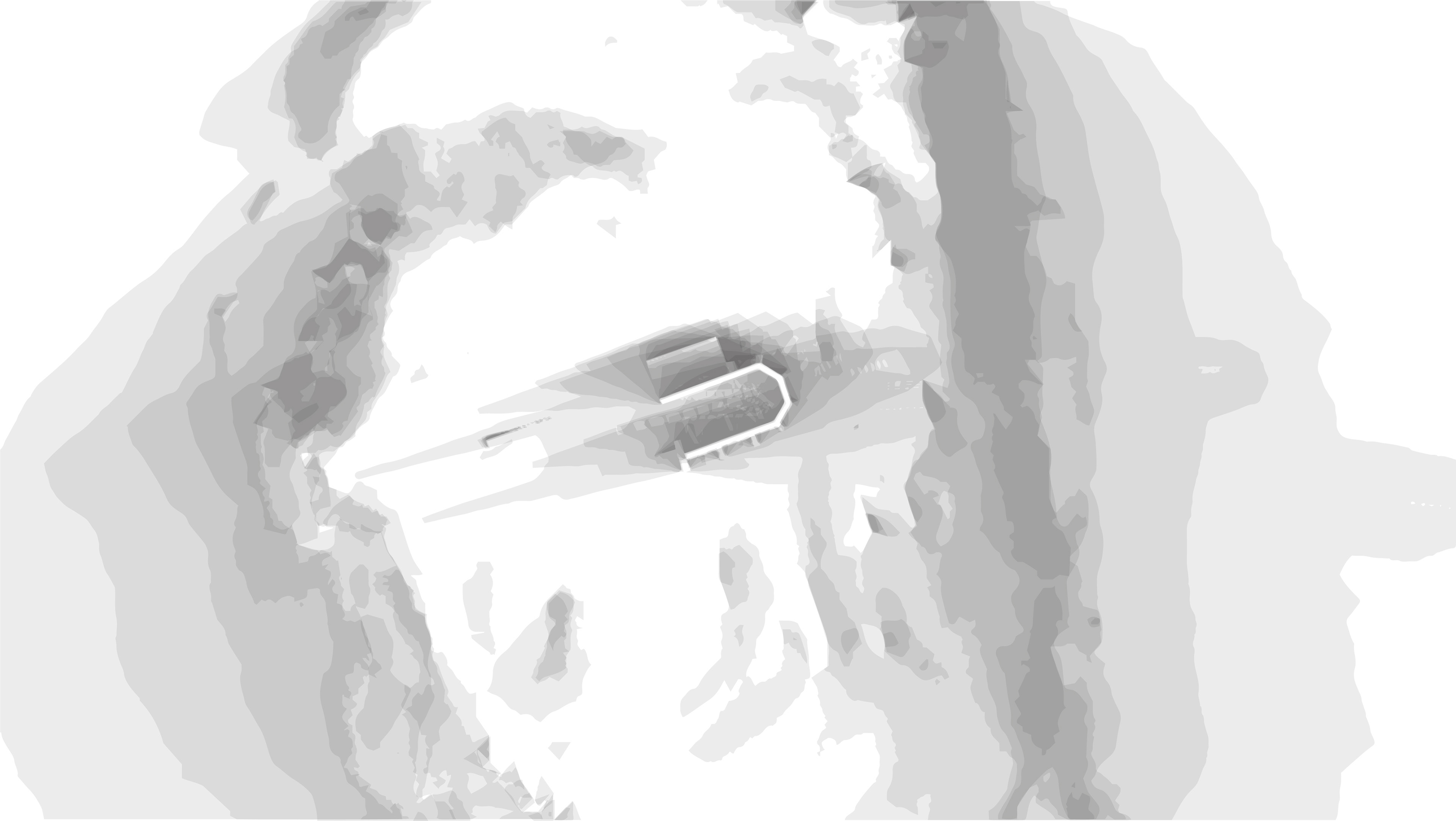

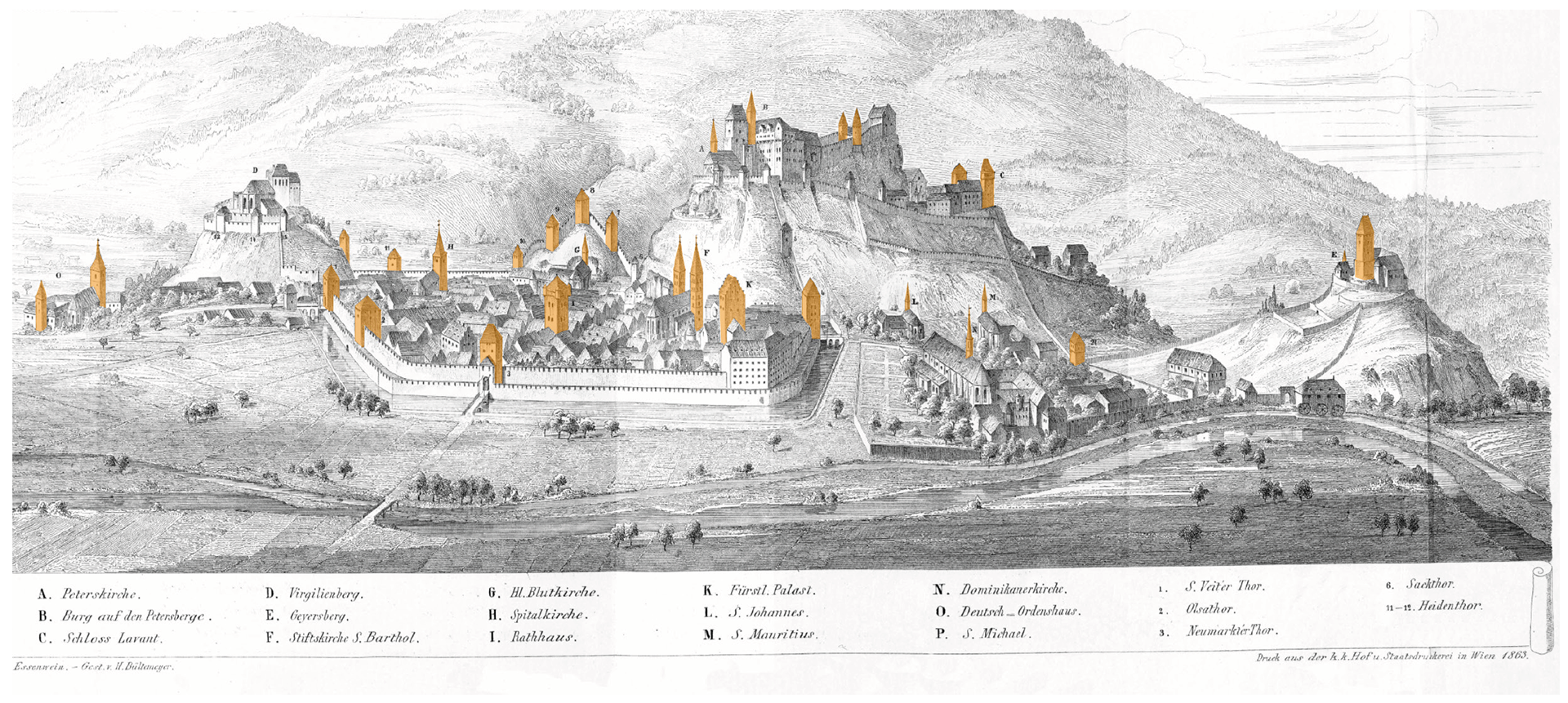

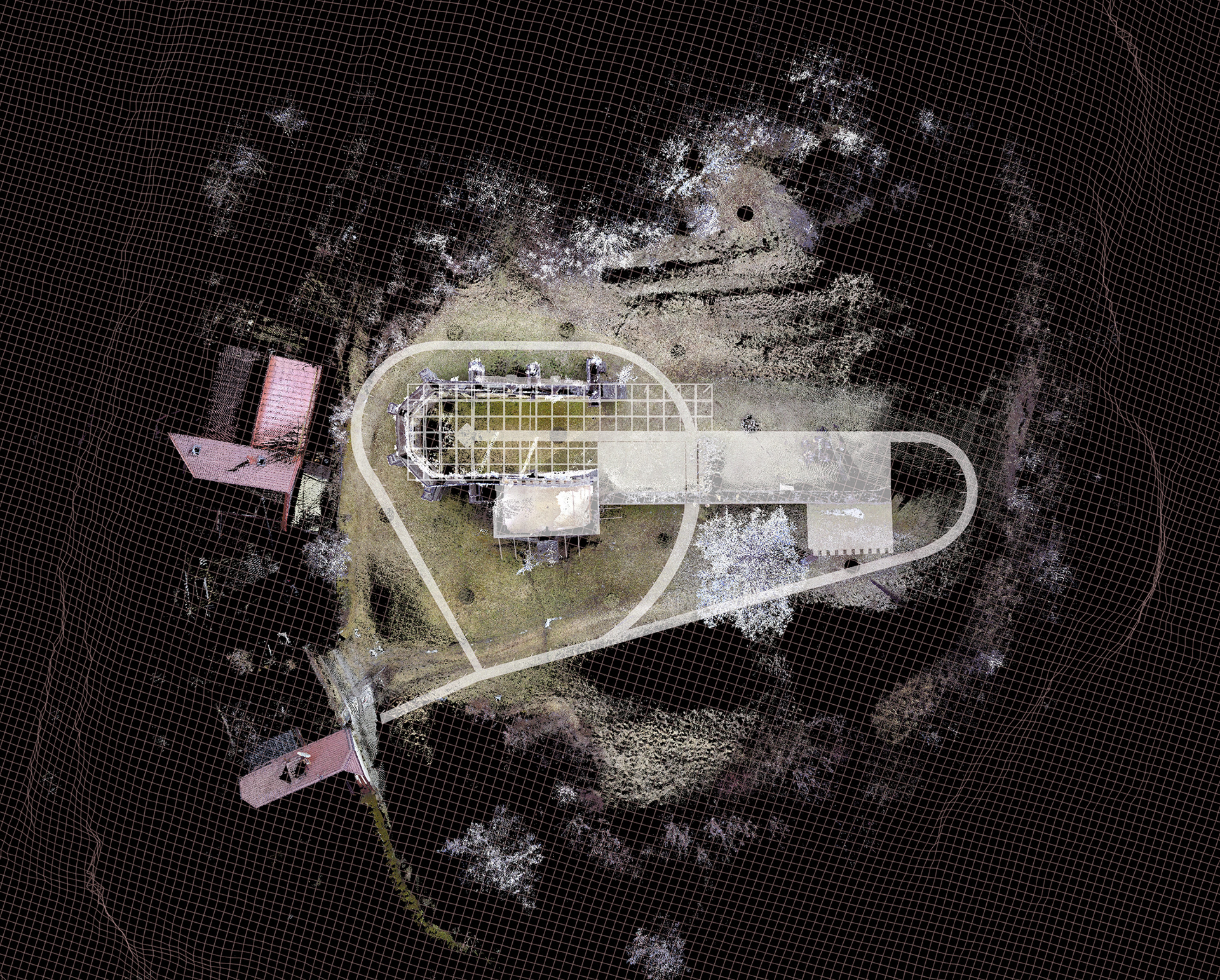

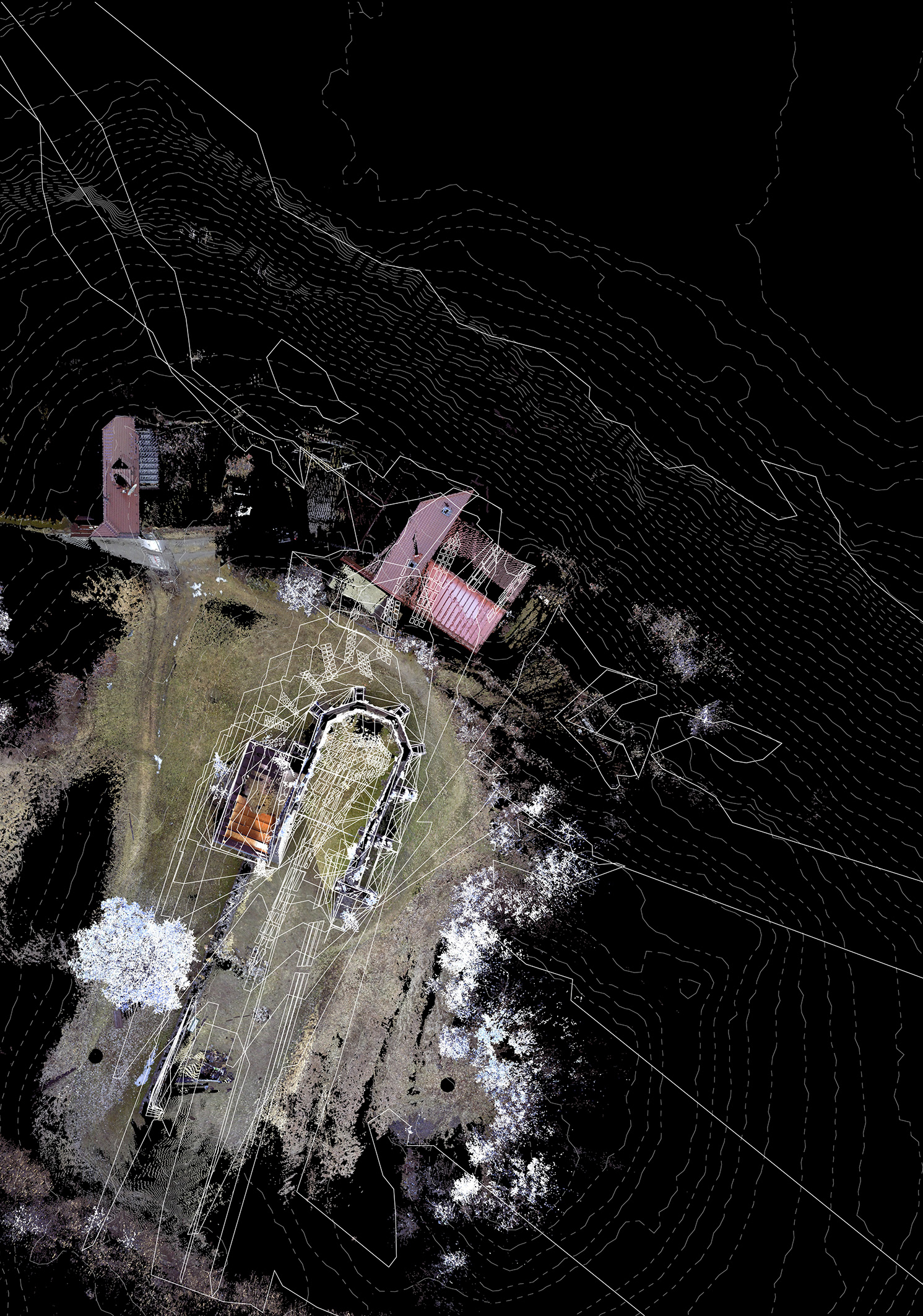

Our testing ground is the Community of Friesach, the oldest in Carinthia whose fabric is defined by medieval constructions, much of them abandoned ruins. Friesach today, despite its prettiness, suffers from a higher-than-average rate of unemployment and few people live within the town wall. Efforts at regeneration so far have been mainly directed at investment in tourism, a strategy which has proven disappointing at best and absolutely catastrophic during the current pandemic. Our site is the Virgilienberg, a hill in the town centre with a plateau at its top where the remnants of a Gothic ensemble (Collegiate Church) built and maintained from the 13th to the 16t centuries lie decaying.

Motivated by the hypothesis that when a community decides to Maintain, Repair and Regenerate shared built spaces together over generations, it also maintains, repairs and regenerates itself, the students discovered and developed six very different possibilities. They are all deliberately open works of architecture and actively invite tinkering, adjustment and improvement by an ambitious community intimately connected with their future. When we consider that global human made mass has now exceeded all living biomass, the maintenance repair and regeneration of what we have already made is the least damaging alternative for the creation of built spaces short of not building anything more at all.

Departing from ideas about the embrace of collision, we embarked on a quest to unearth forgotten values; values that architecture has ceased to offer: the Savageness, Changefulness, Naturalism, Grotesqueness, Rigidity, and Redundancy of the Early Gothic[1] Cathedral. These were the terms that, in 1852, John Ruskin used to lovingly describe, The Nature of Gothic Architecture[2]. But during our journey we discovered the role played communities and the endless rebuilding of Gothic churches, so that our tentative arrival was drenched and suffused with the beauty, importance and urgency of Maintenance, Repair and Regeneration.

[1] What you call Gothic architecture was, at the time it was first practised in the 11th century, probably referred to as modern. It ushered in a similar, if not more profound revolution in built space to what you call Modern architecture today. Giorgio Vasari, a Florentine painter, writer, architect and historian (1511-1574) probably coined the term in his Lives of the Artists, likening it to the Visigoth culture, mistakenly conceived of as barbarous. He preferred the perceived purity and regularity of classical architecture. The assumption that purity and regularity is a positive attribute is one that has proven particularly tenacious and, indeed, nowhere more so than in what you call Modern architecture today.

[2] The Nature of Gothic architecture in the second volume of, The Stones of Venice, the second volume of three entitled, The Sea Stories, published between 1851 and 1853, by Smith, Elder & Co., London.

[1] SarS Covid-19

[2] SMASHUP embraces productive collision in architecture. Perceives architectural entities as elastic, exchanging influences and exerting attractive powers. Aims to supercharge argument, challenge taste, preconceived ideas and laissez-faire politics. Confronts strong propositions with each other and ask them not only to coexist but to improve.

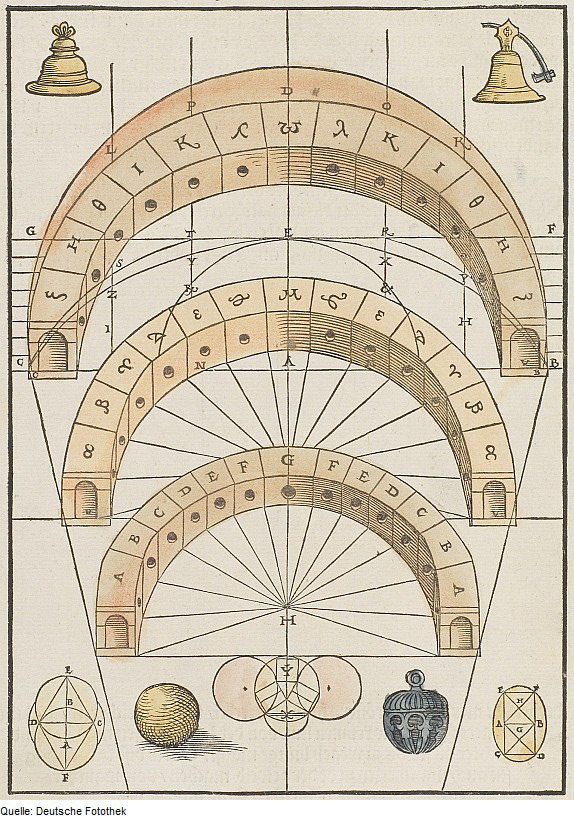

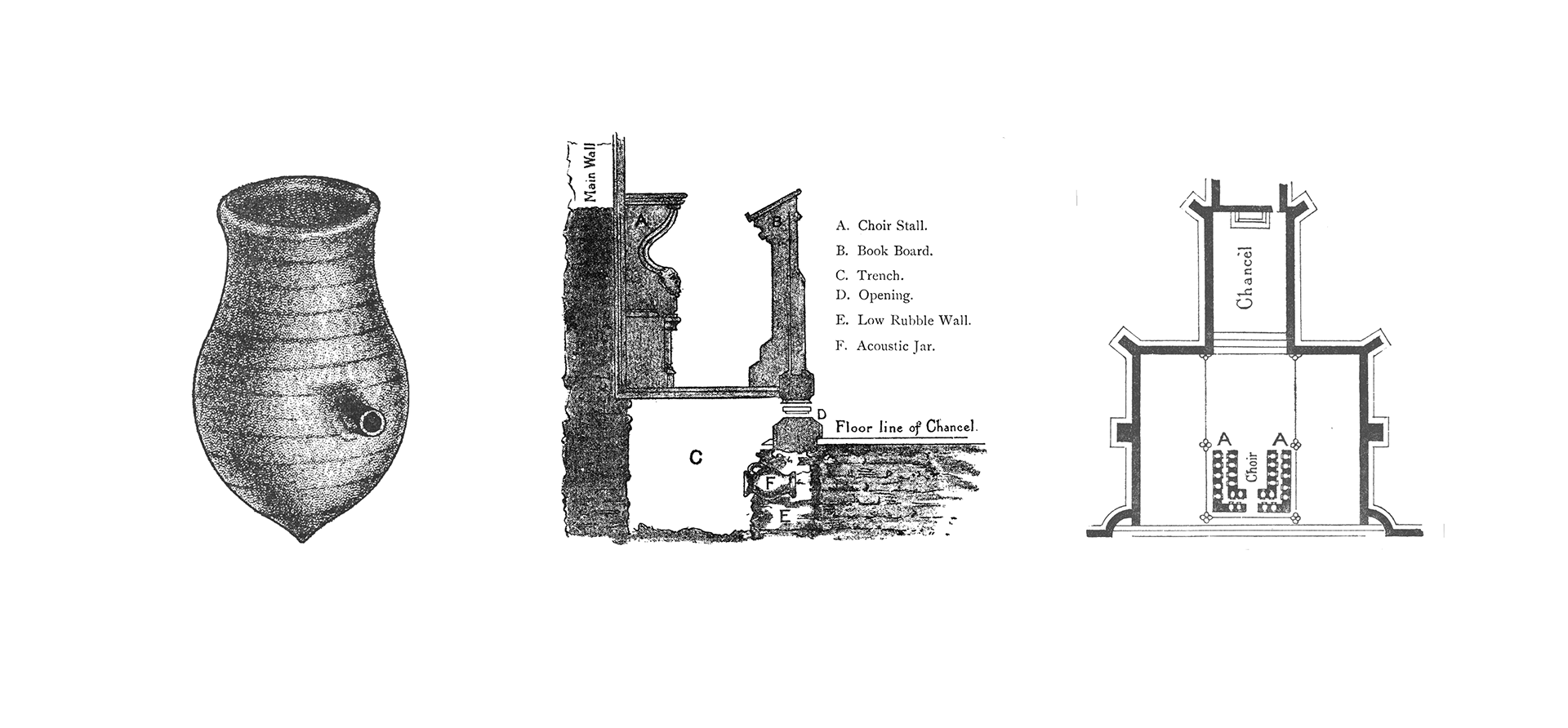

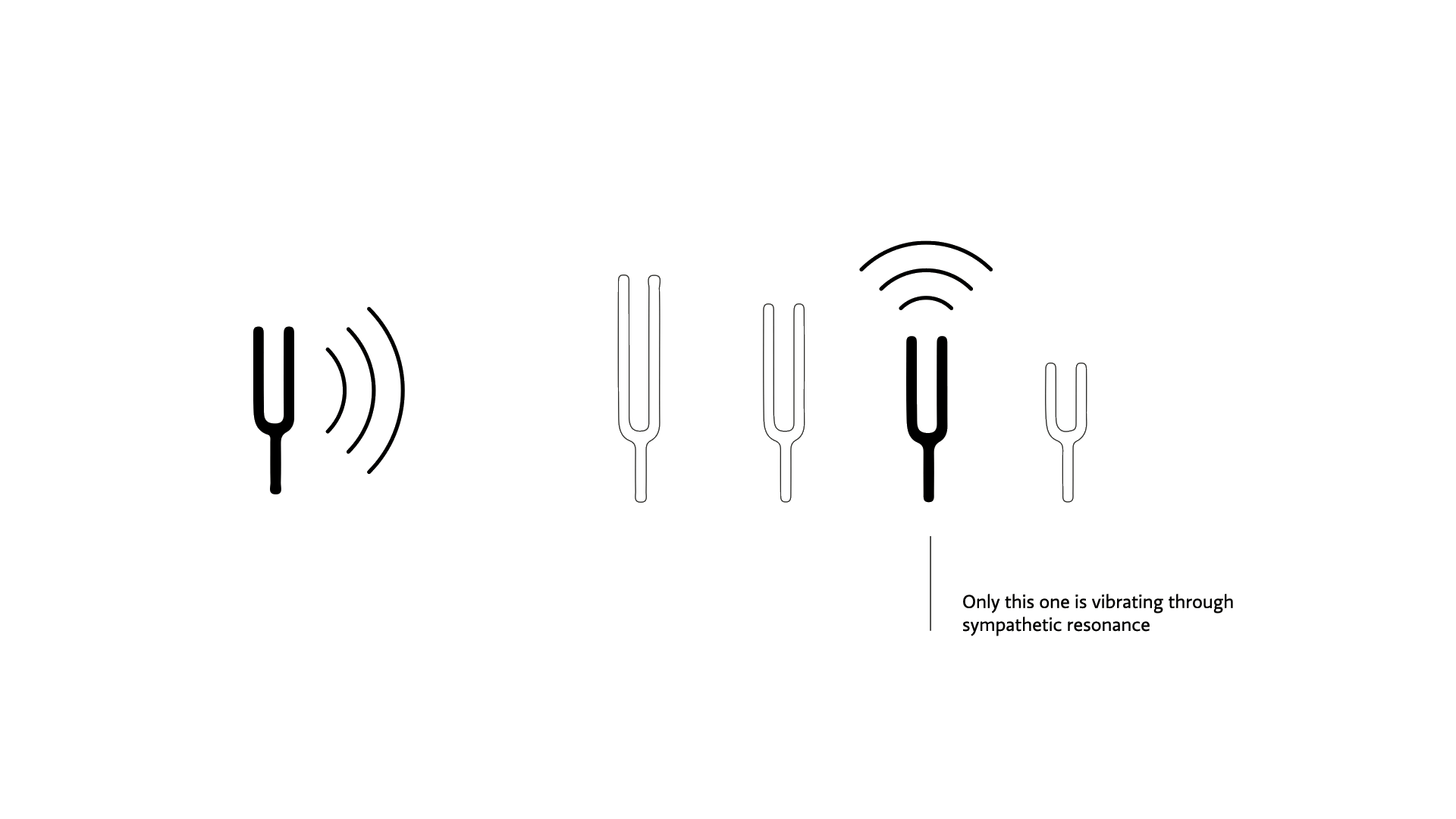

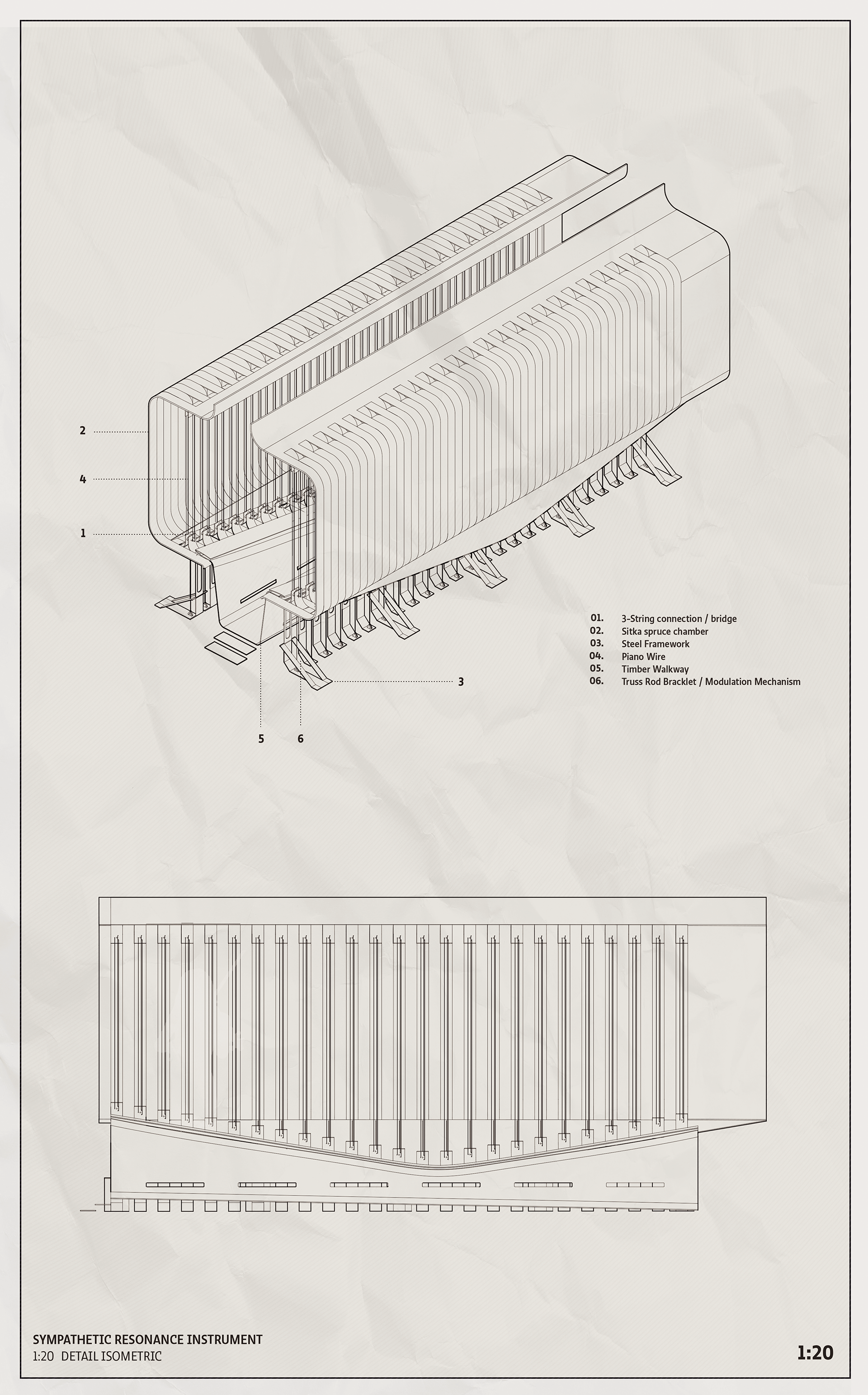

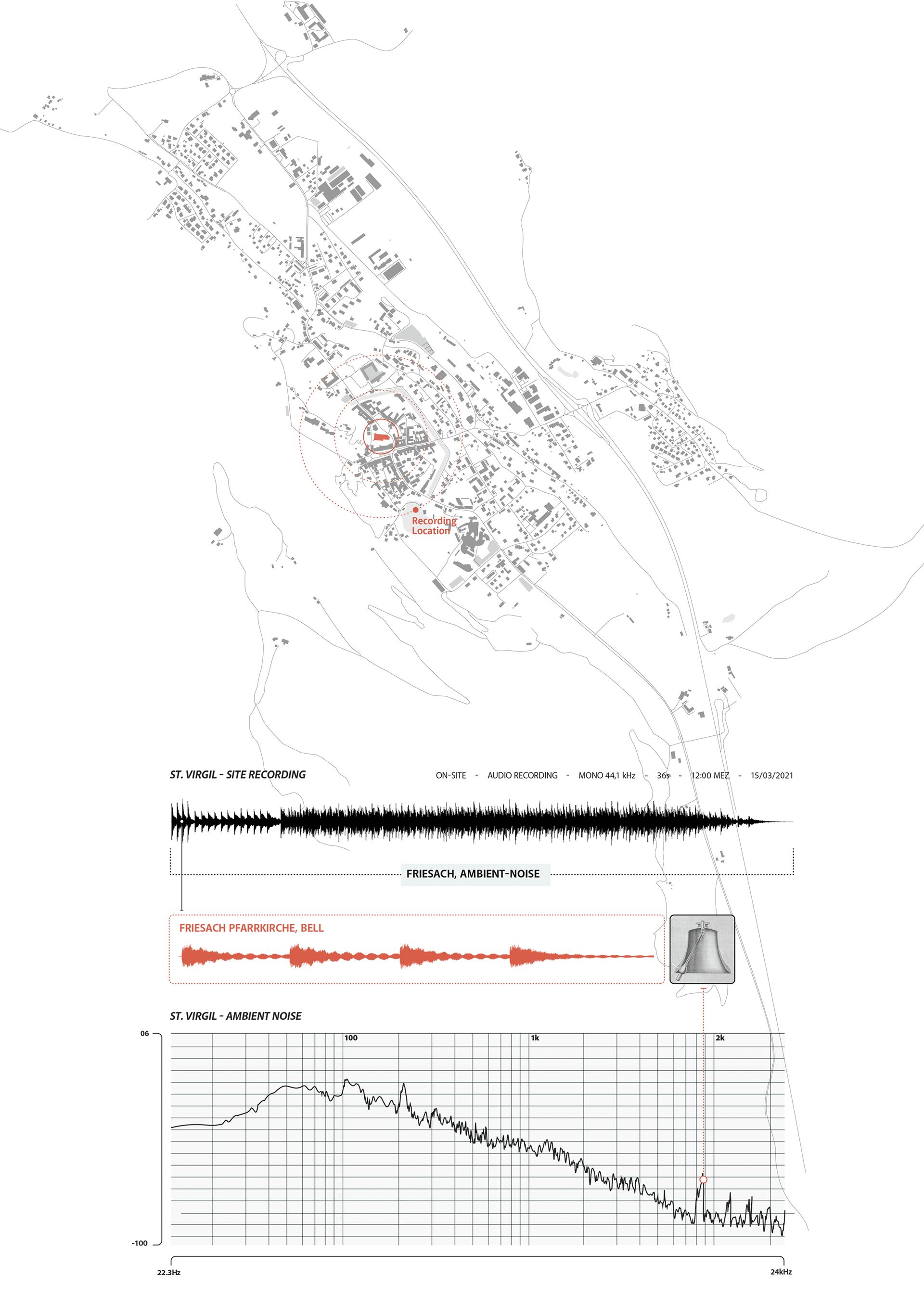

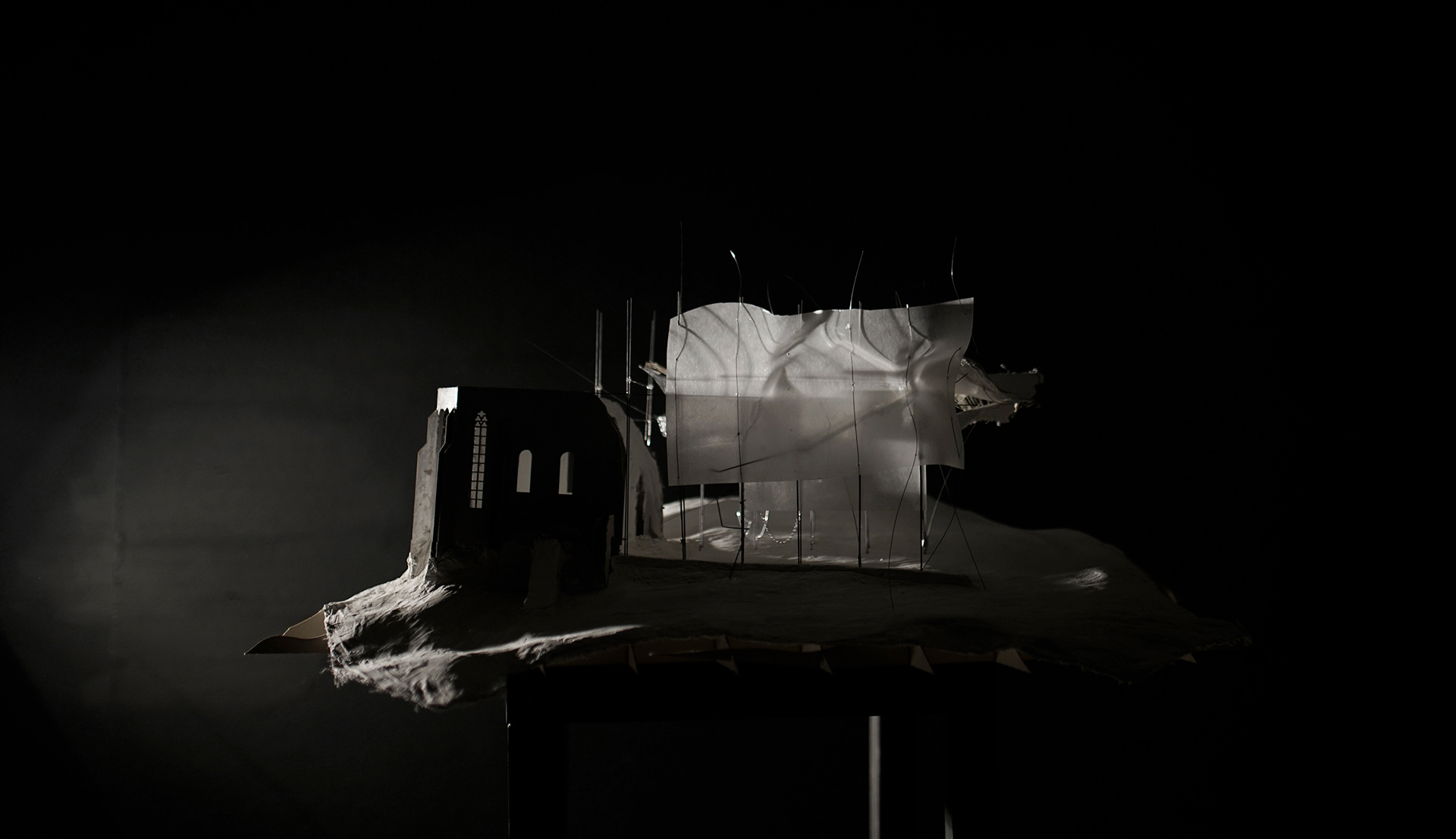

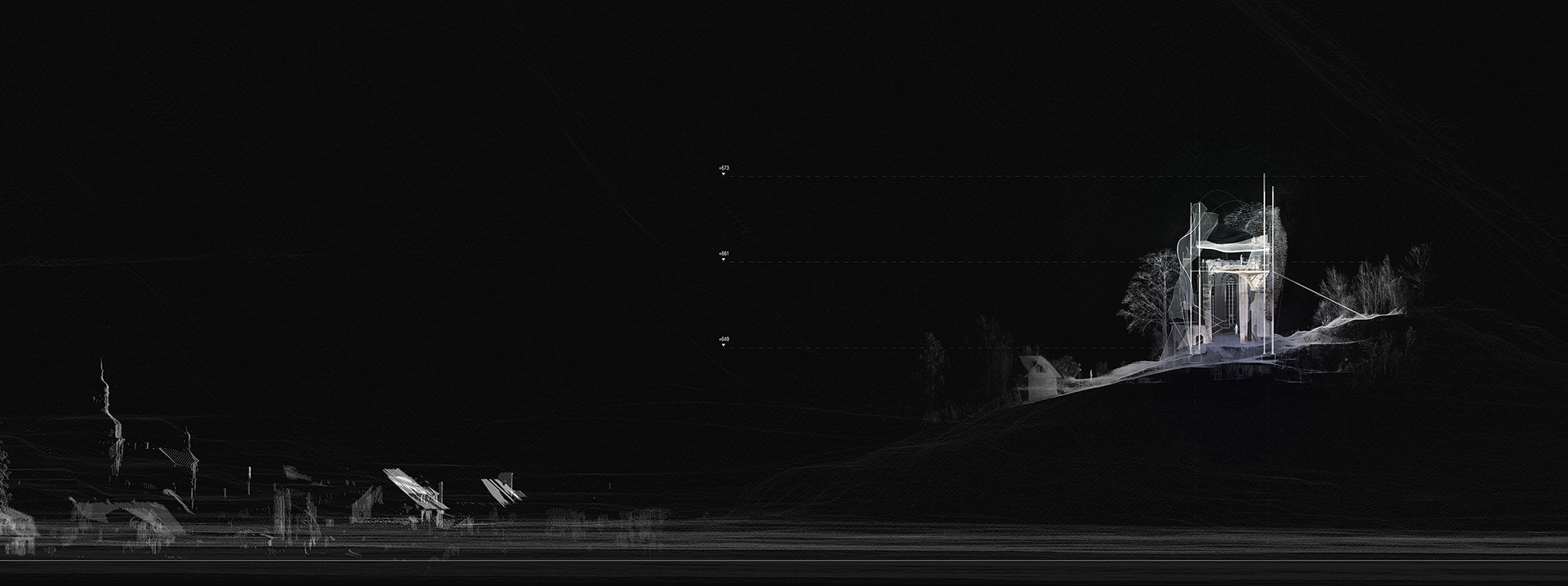

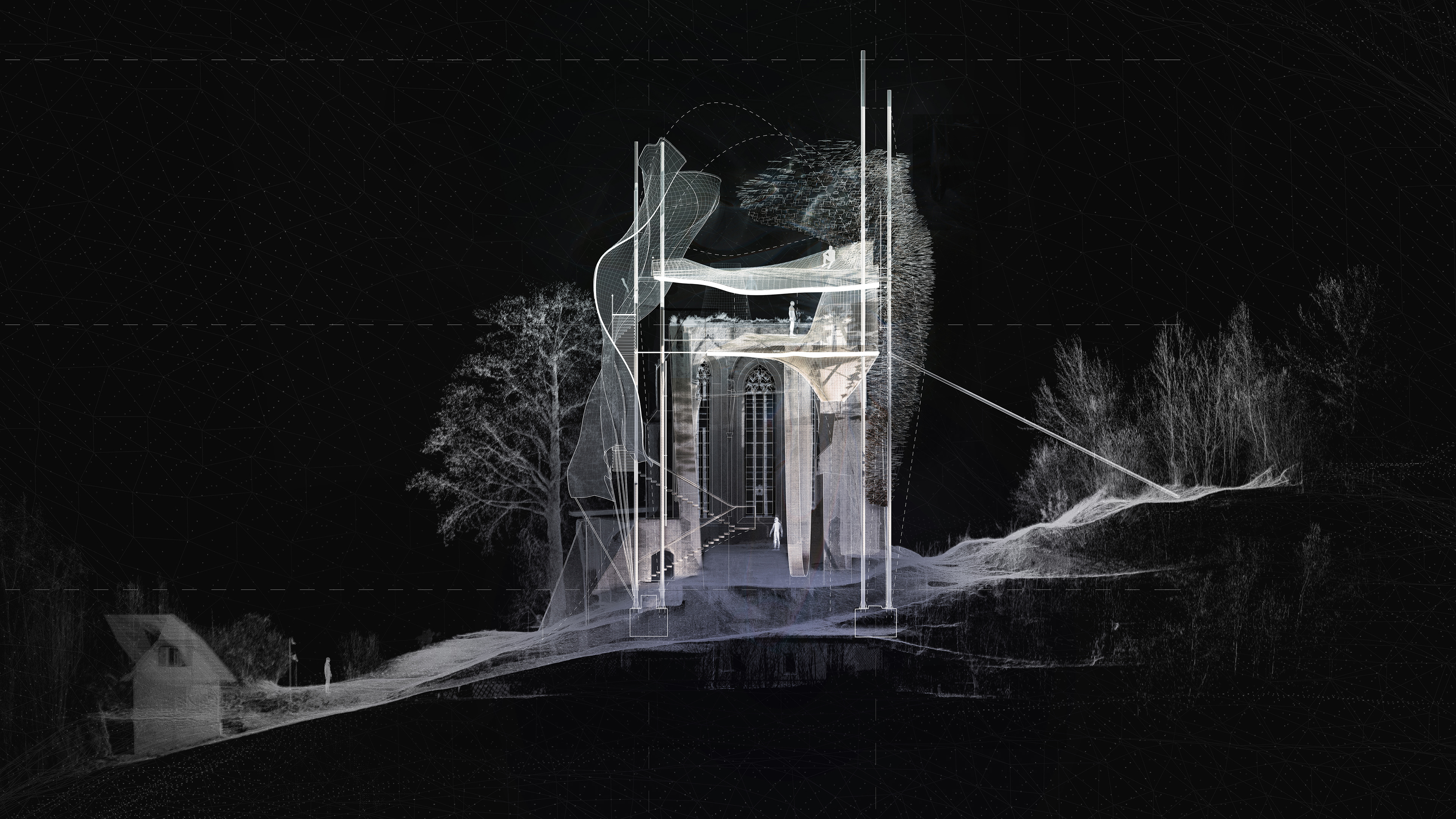

Julian Berger—Ode to a Ruin

Just as the now vanished bell tower gave rhythm to the days of the inhabitants down below through the pealing of its precious bells, marking the milestones of the medieval day, Julian Berger transforms the Virgilienberg into an experimental tonal space and an instrument activated by its microclimate. Inspired by ancient acoustical techniques such as the insertions of wooden instruments and ceramic vessels within the walls of stone and the wind blowing through the unglazed windows and their surviving stone traceries, Julian proposes a project which begs to be instrumentalised by its community.

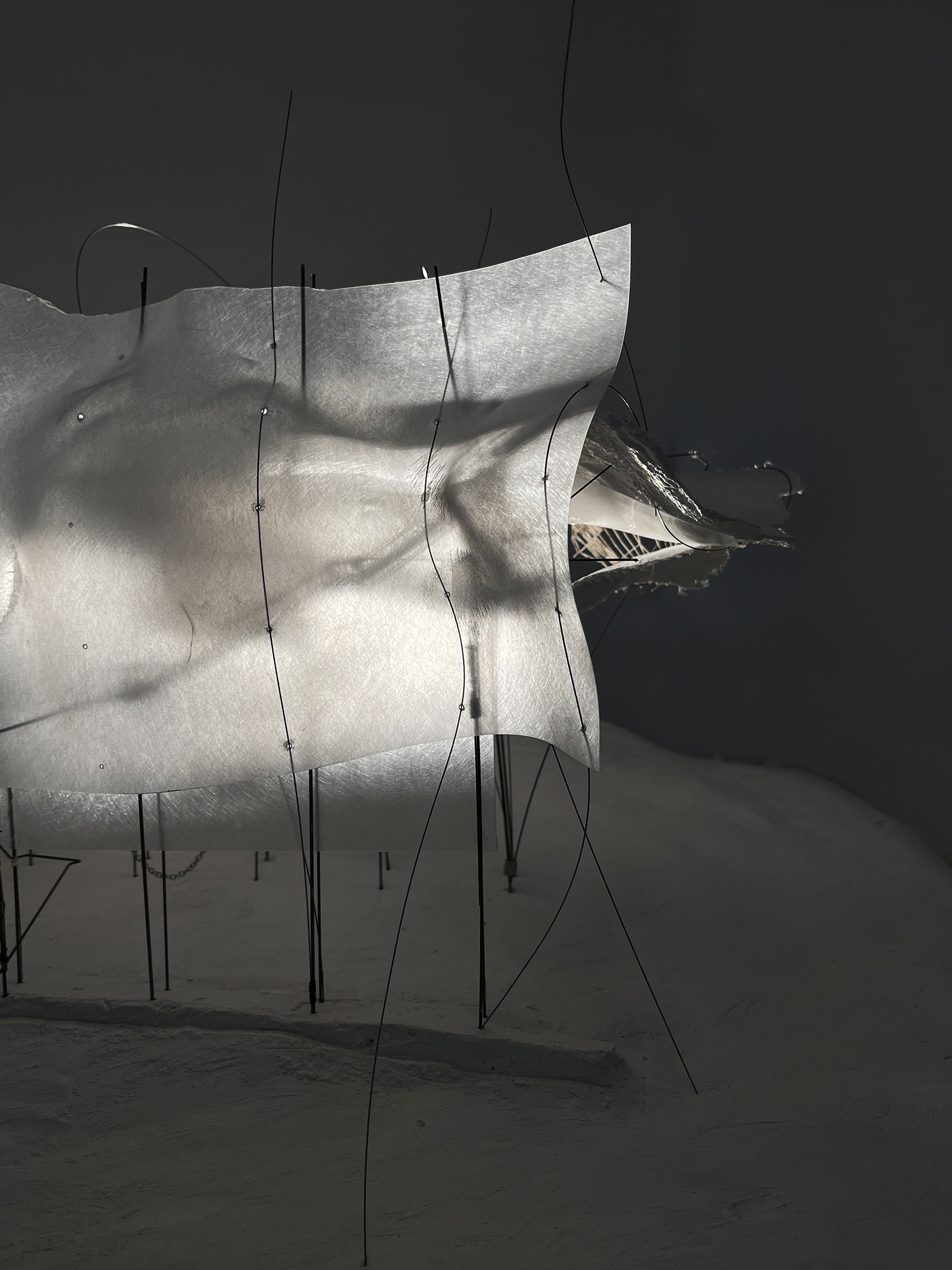

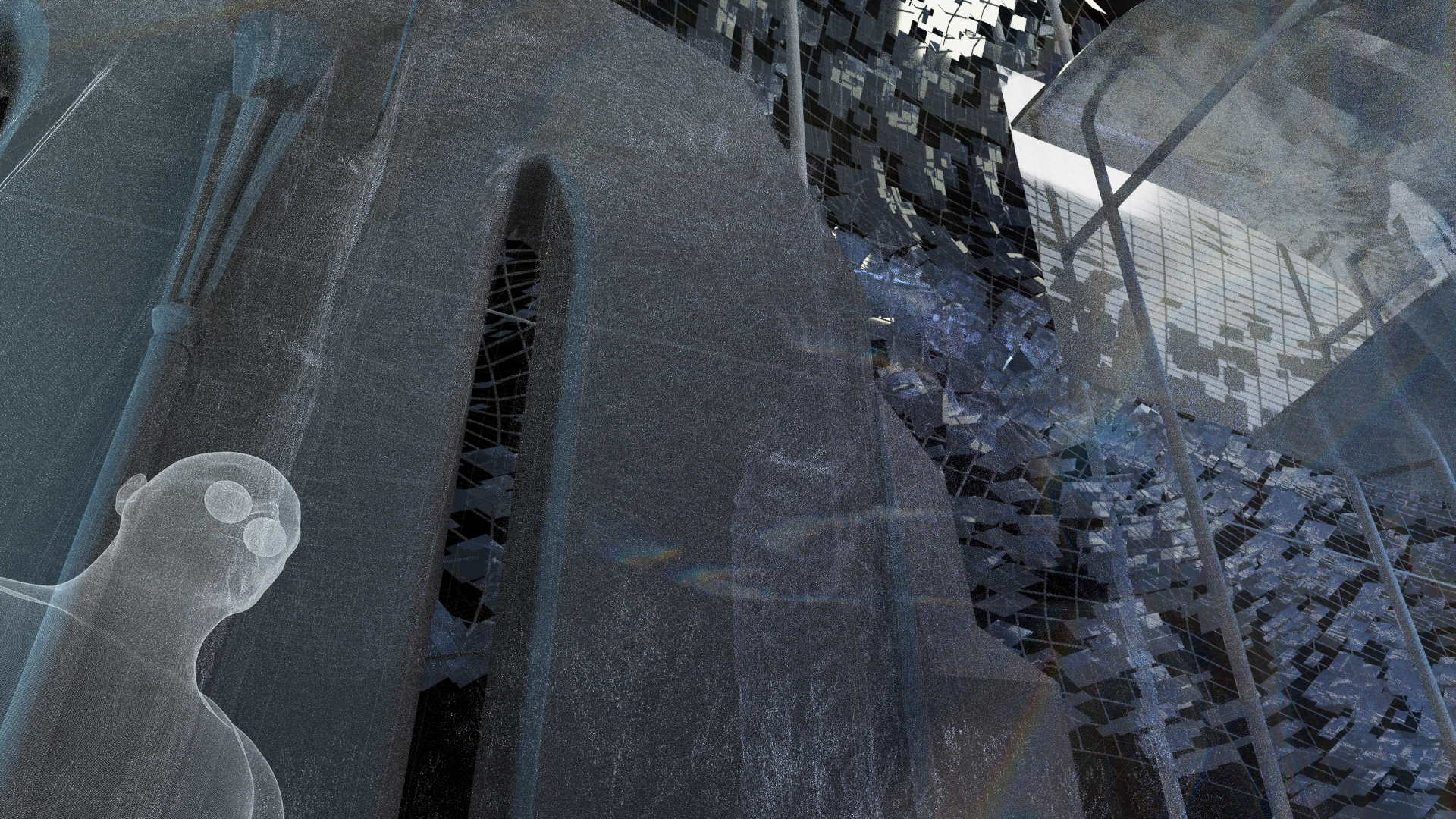

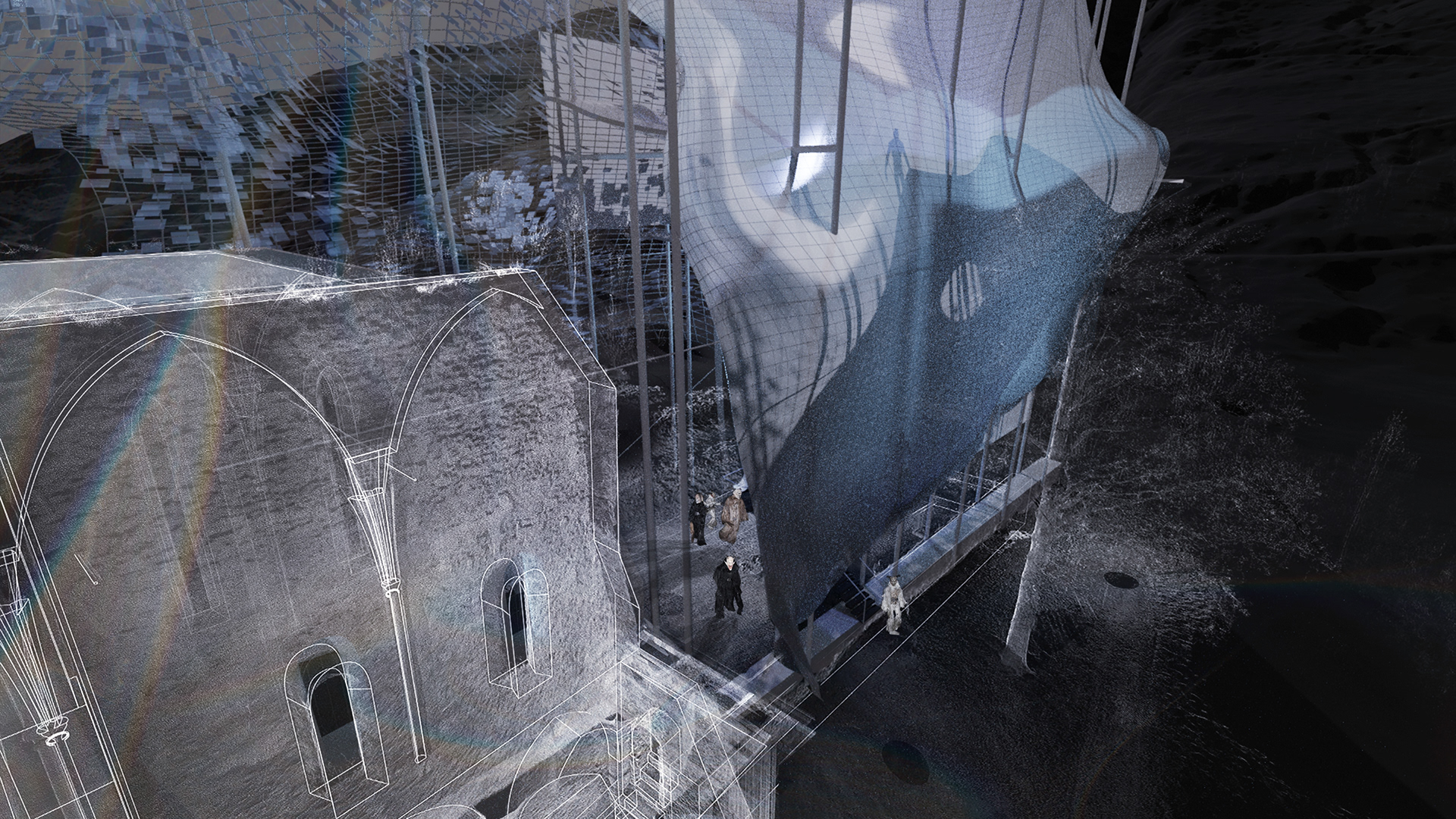

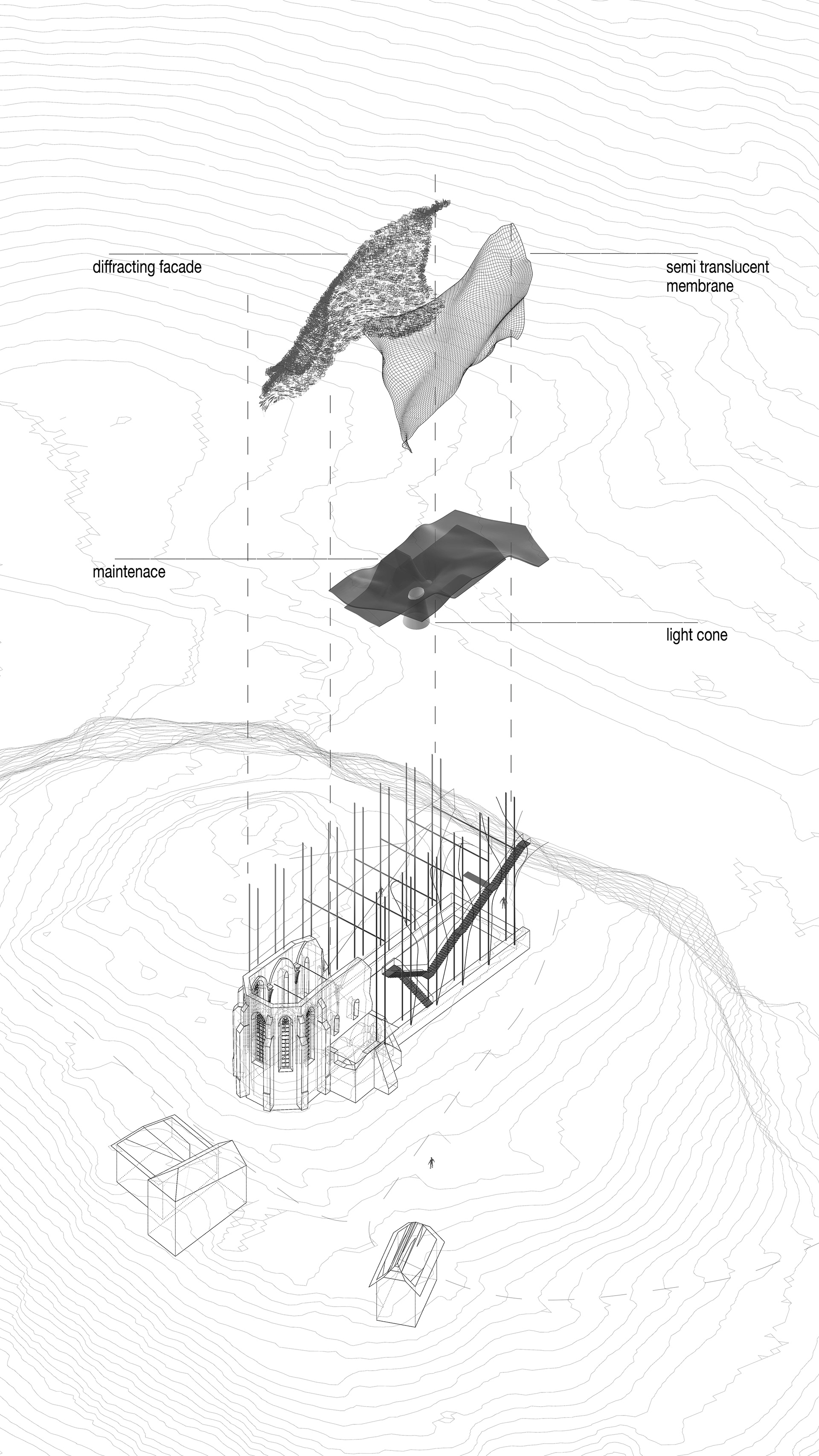

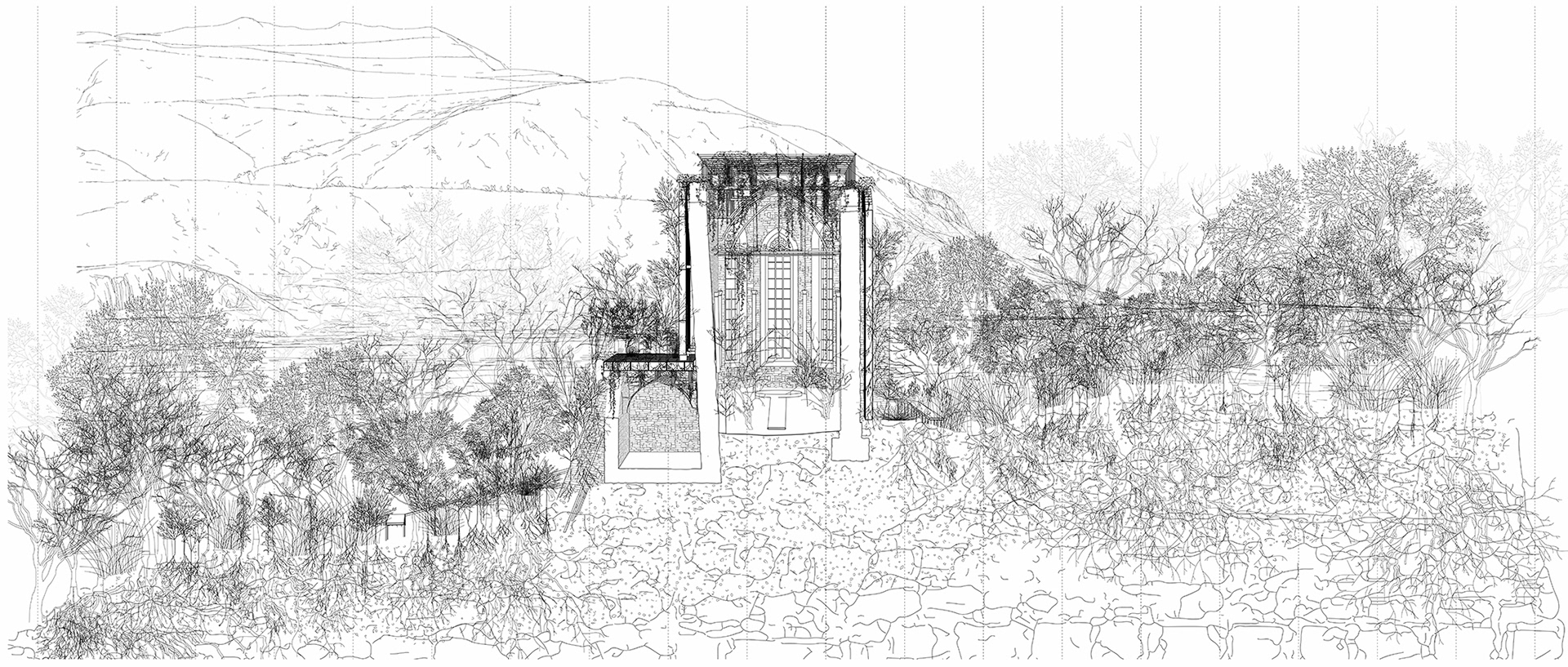

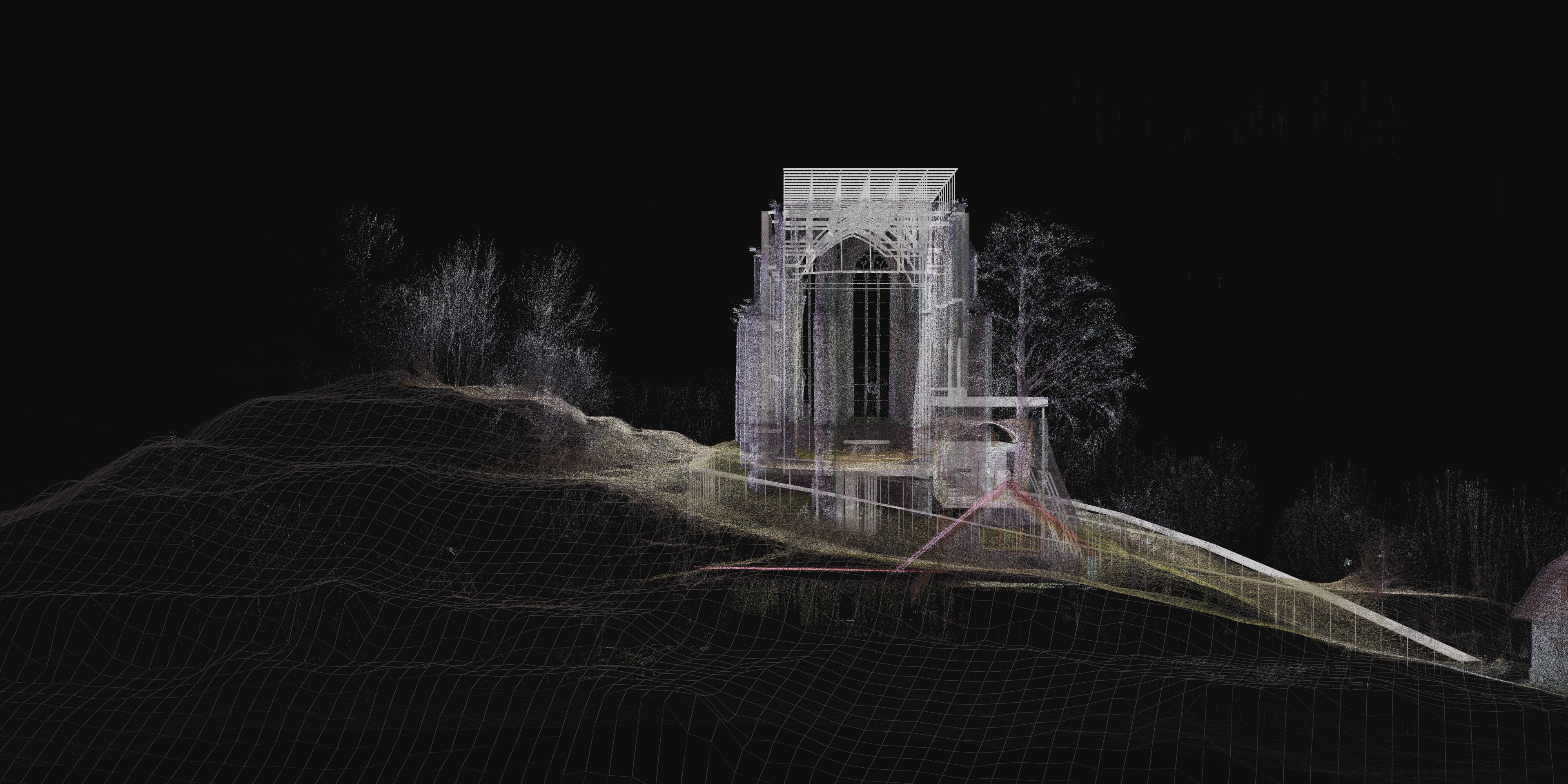

Paul Böhm—Head in the Clouds

Paul Böhm pursues the Diaphane, a medium characterised by such fineness of texture that it can be seen through and makes visible all that it covers. This translates into a project which seeks to permit many people to gather in a place sheltered from the elements yet still climatically open and reminds us of the important role played by the vastness in the indoor spaces of the early Gothic church and the daylight which filled them. Just as in the stained glass which no longer exists but still resonates, his Diaphane irradiates, tells stories and encourages the community to plunge their heads into the clouds.

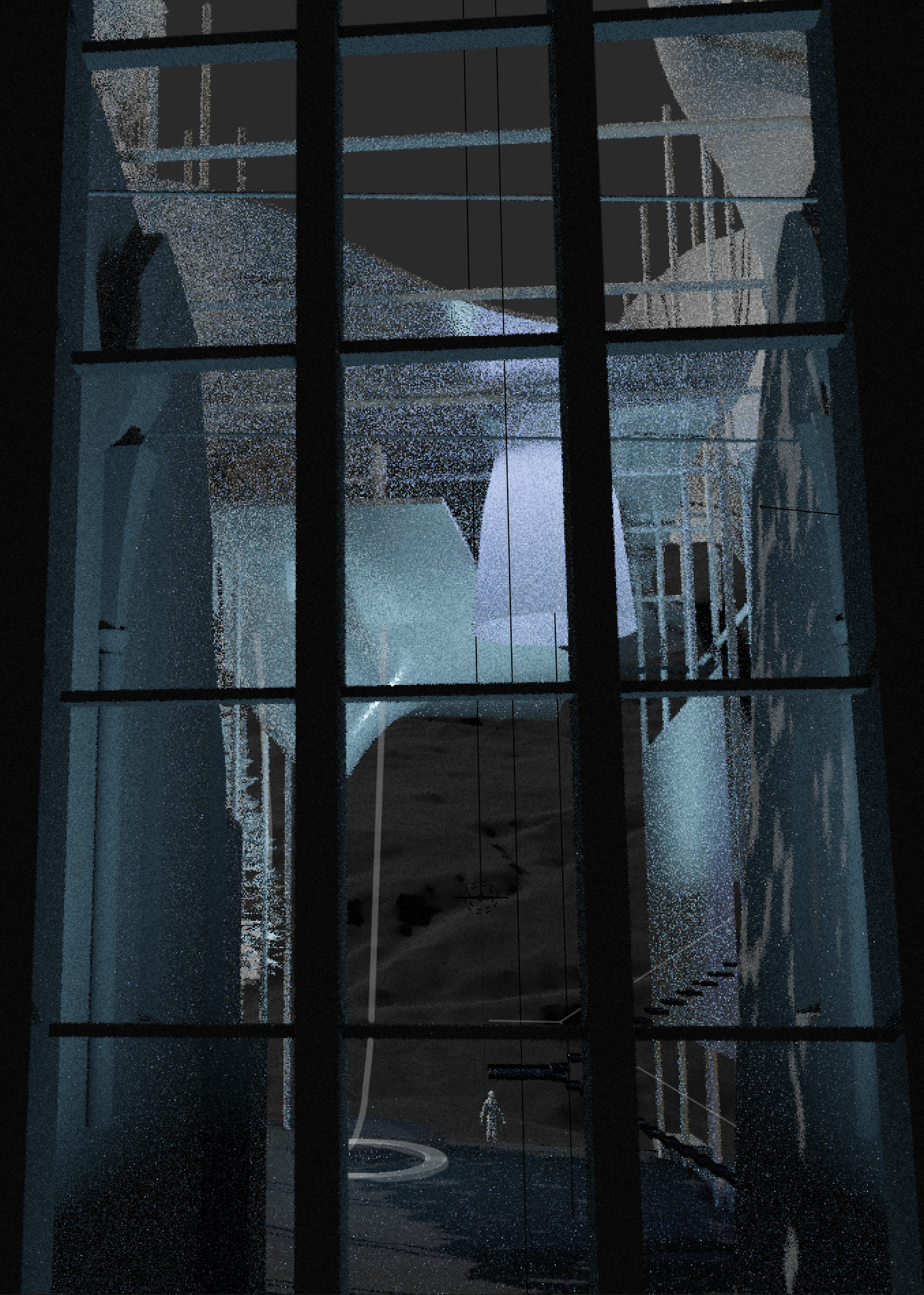

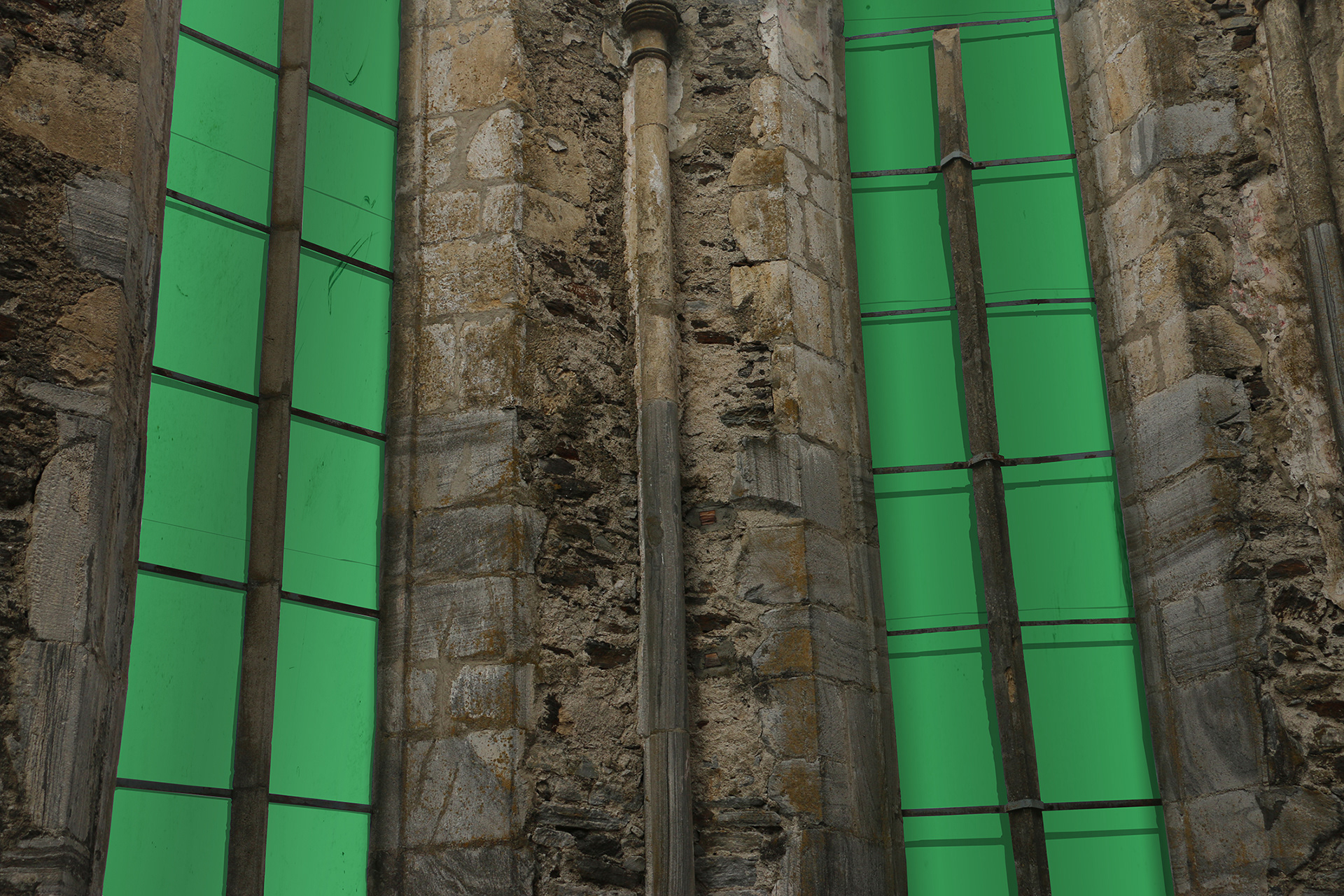

Daron Chiu—Ruinen Lust

Appearances and make-believe are at the core of Daron Chiu´s project. Using the technology of the green-screen, a method for inserting costumes characters into any background developed for cinema in the 19th Century, he proposes a construction which bridges the real world of the medieval ruins and the fake one constructed to accommodate tourism in pretty ancient towns like Friesach. Green was chosen because it was the colour least likely to be worn by protagonists. The project focuses a critical eye on tourism, localisms and the sense of belonging and identity.

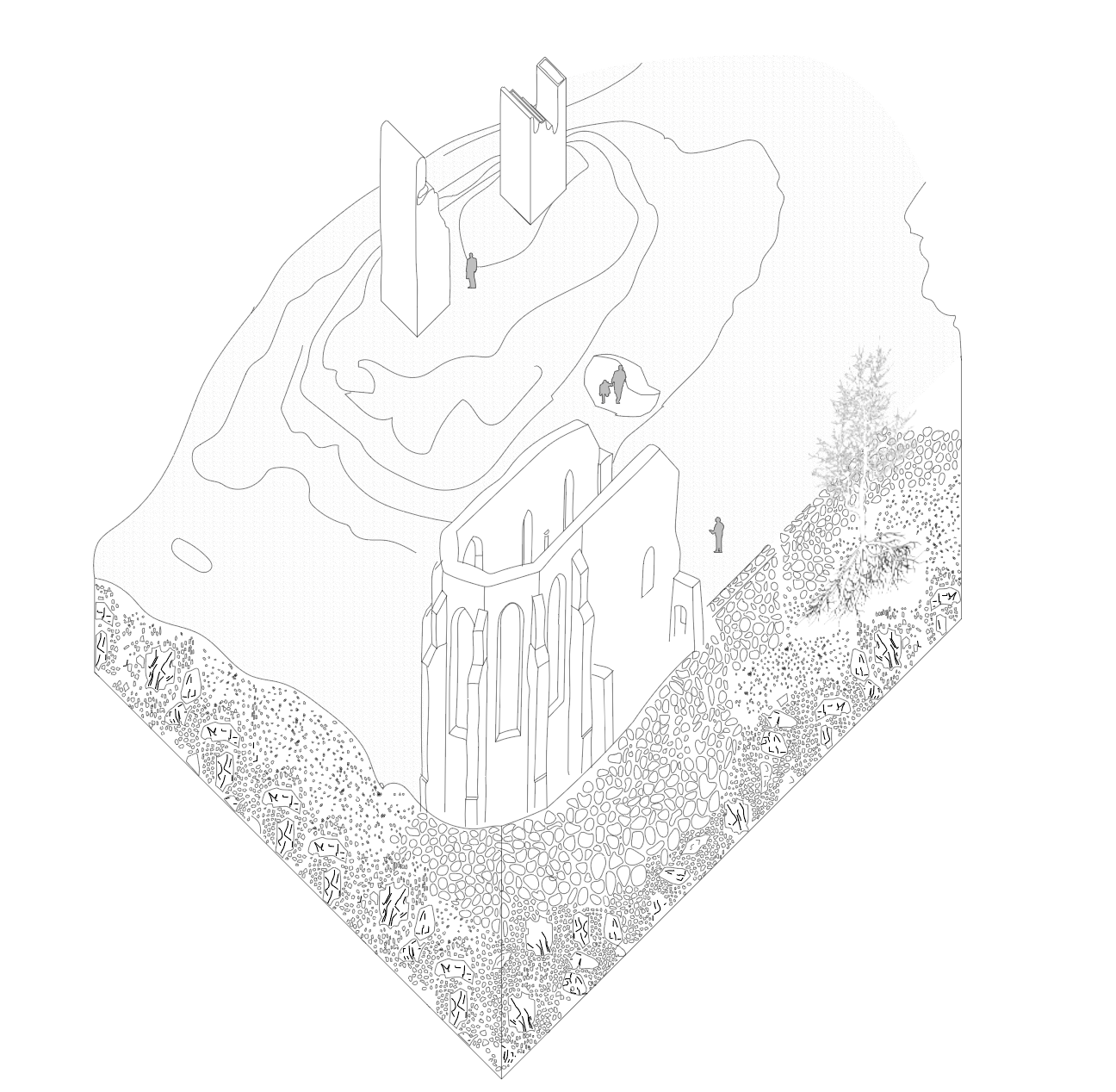

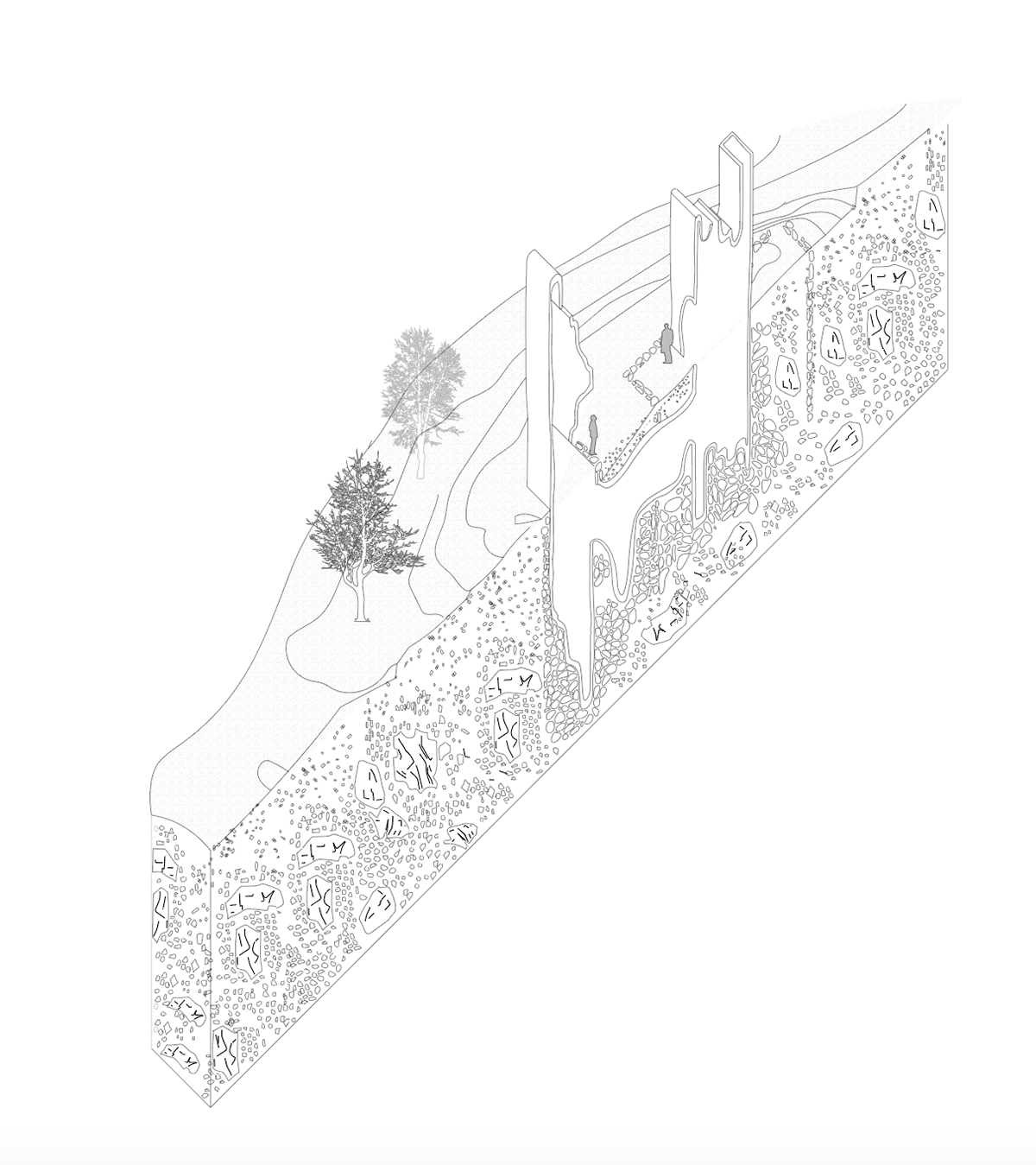

Lauren Marchand— From the Ground Up

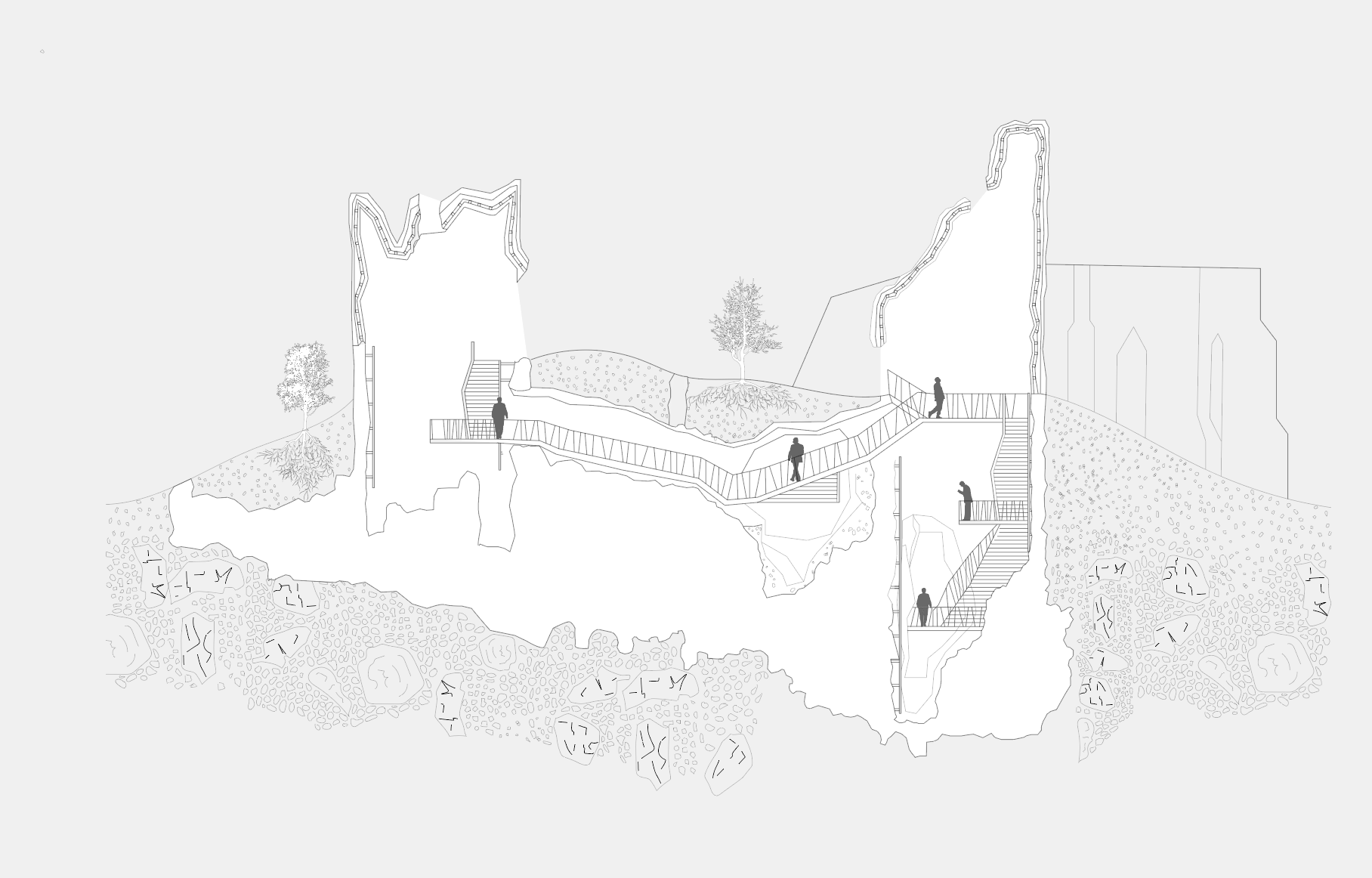

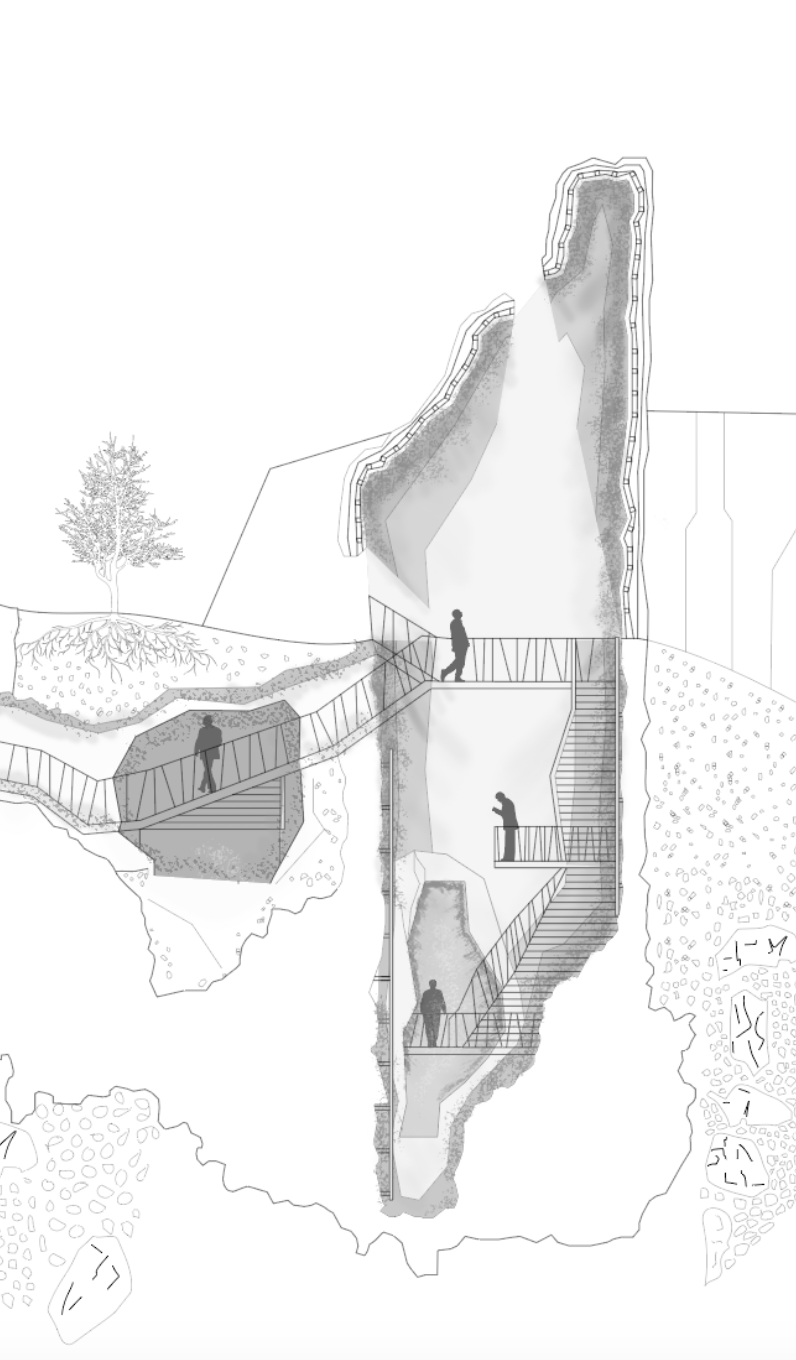

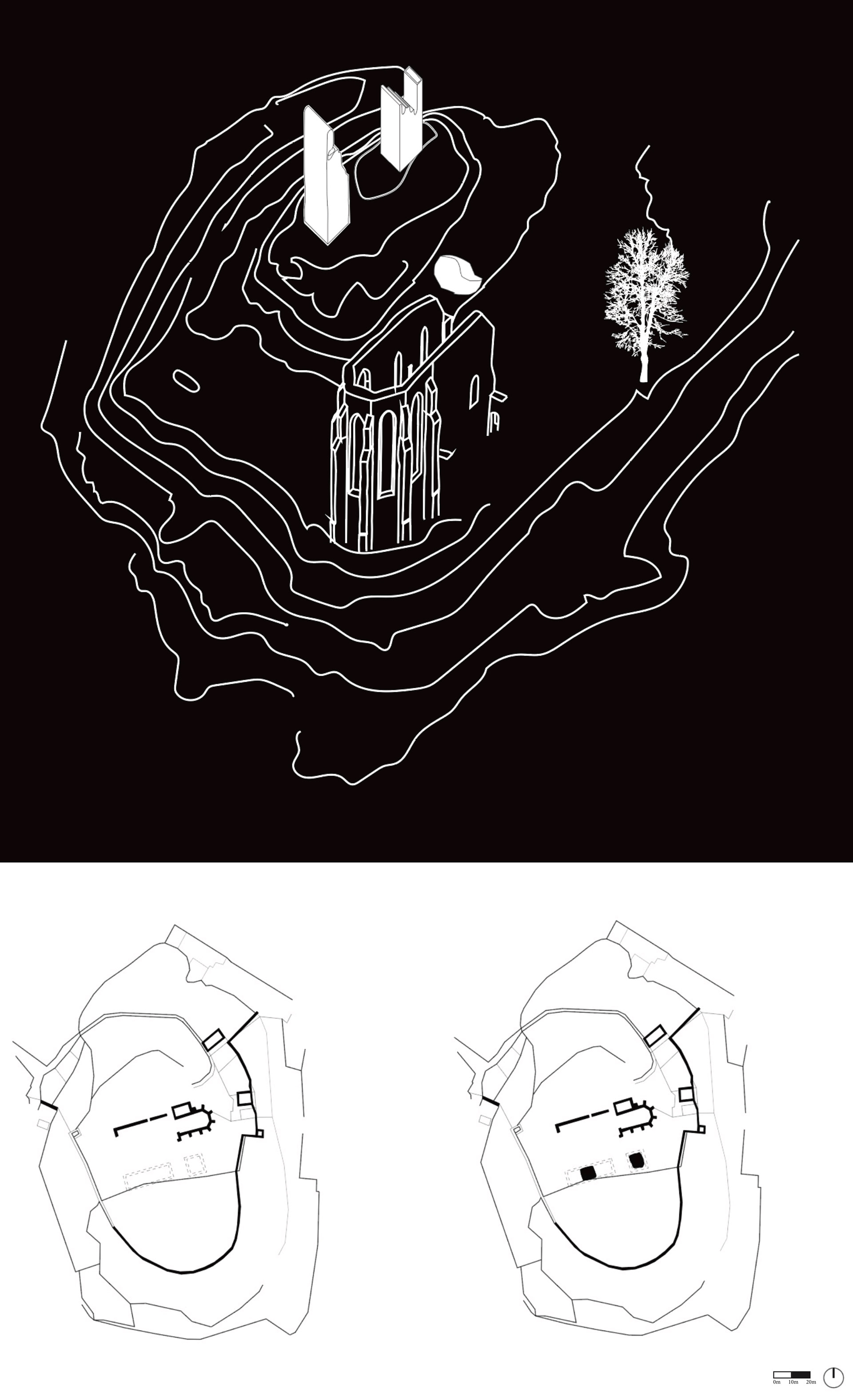

Lauren Marchand is fascinated by the idea of the many layers which have built up in the constant rebuilding and regeneration of this site and its many stone constructions, keenly aware that the built environment underground that is not visible could probably be just as, if not more rich than that which is visible and above ground. She digs into the groundscape within and without the visible remains of the ensemble of buildings which constituted the collegiate of St. Virgil. The resistance of the soil and the shape of the old stone foundations, tombstones and a hidden underground chapel determine the shape of new communal spaces. They are crowned and lit from high above by tall towers which converse with other older towers scattered on the hills around the town and let daylight cascade into the furthest depths of cave-like spaces.

Prima Mathawabhan – Symbiotic Garden

The Symbiotic Garden by Prima Mathawabhan stems from her discovery that the majority of the plants which have found refuge and shelter in the spaces, the walls, the stones and the crevices of the ruins of the church are native to places as far flung as south America and antipodes. The project takes the form of a carefully tended and wild garden which nurtures and protects the existing plants and encourages further species to implant themselves while requiring humans to remain on designated paths as distant visitors or even voyeurs. These plant tourists are encouraged to set root and increase the richness and diversity of the native plant life.

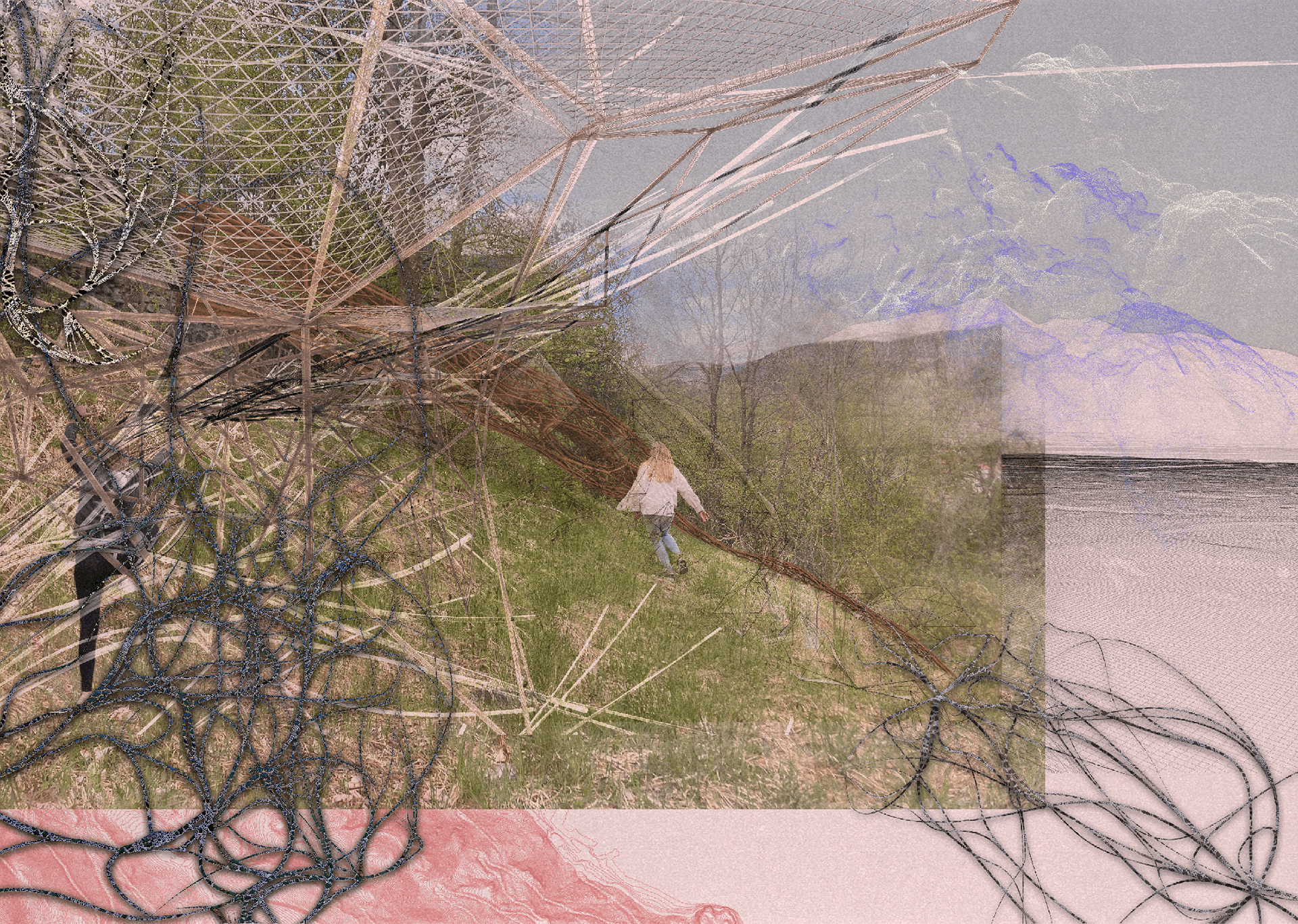

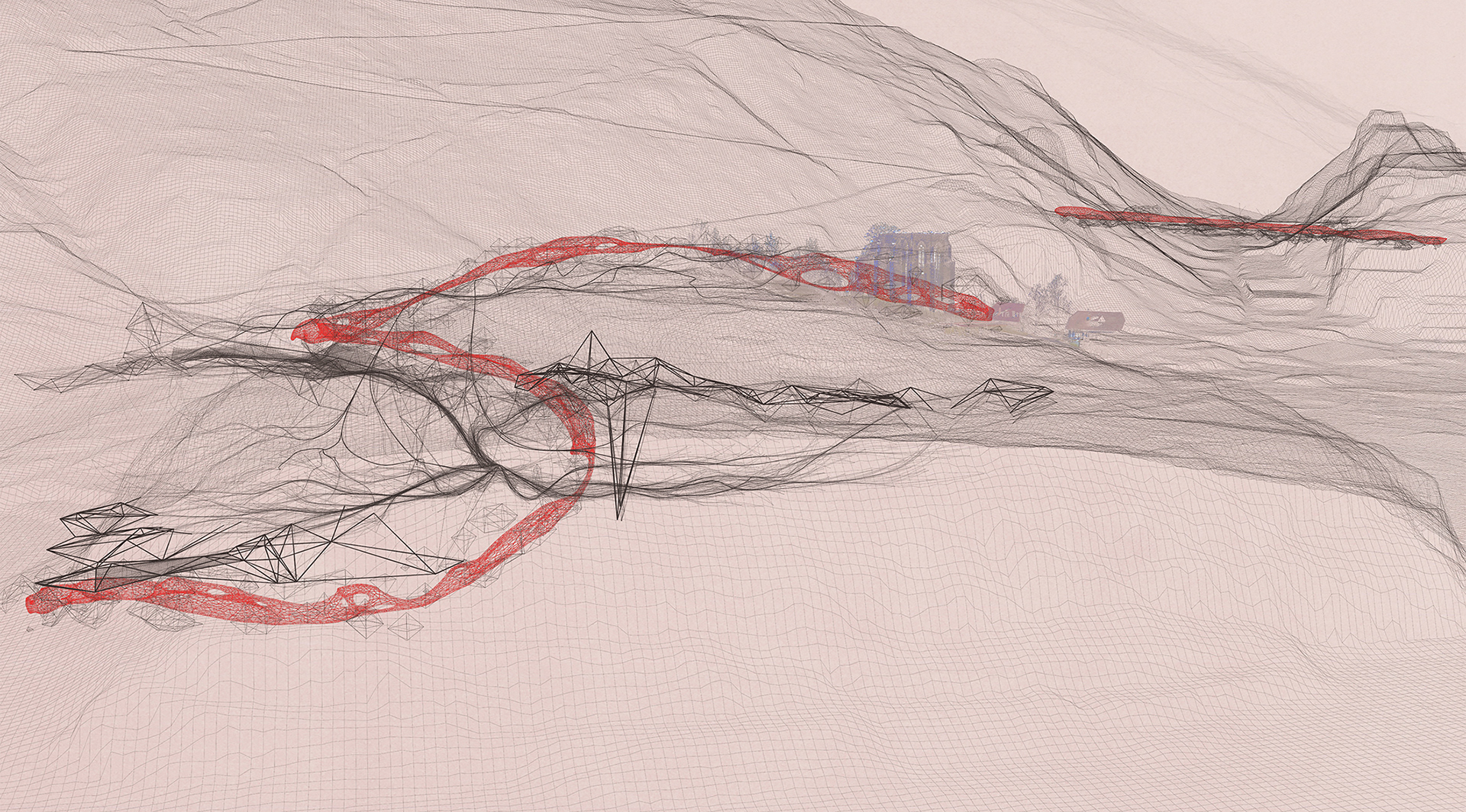

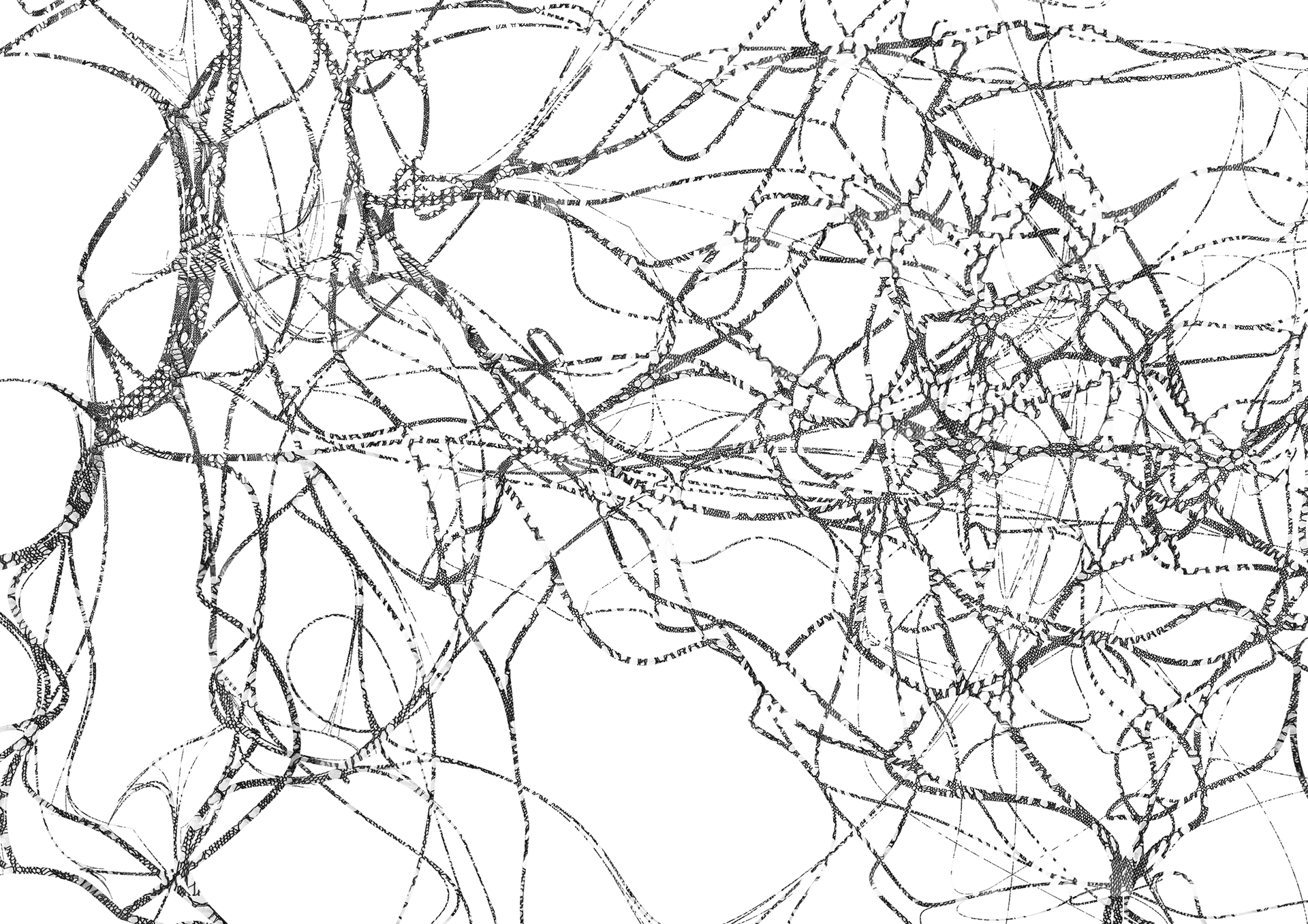

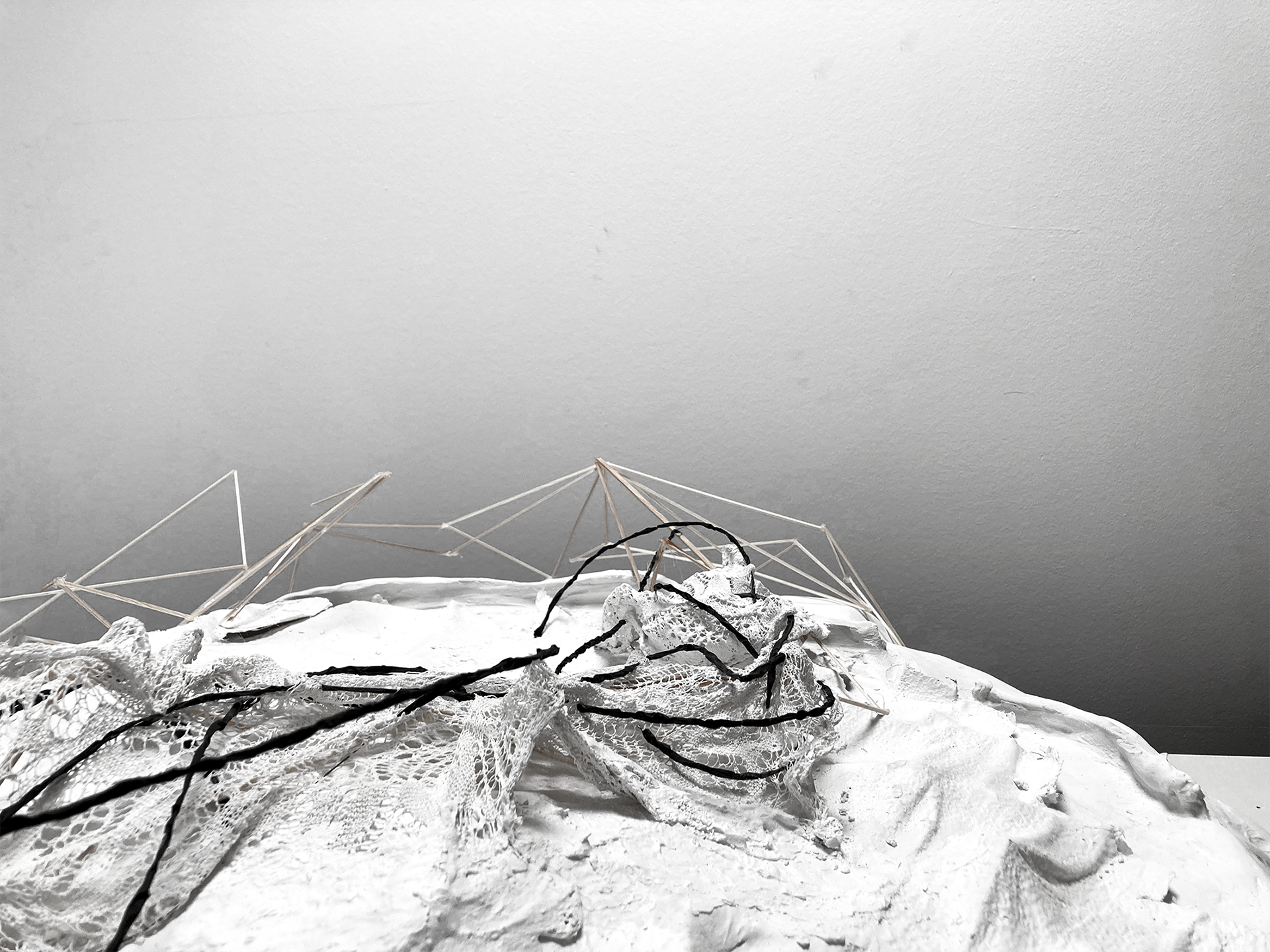

Alina Meyer—Coalesce

Alina Meyer conducted studies into the physical world of movement and connection, seeking out diverse highways and byways, clambering over walls and through hedges, and jumping over streams and gaps in an effort to uncover new physical connections between the town of Friesach and the Virgilienberg. Her proposal establishes these connections not by the creation of new pathways but seeking out, consolidating and improving well-trodden, underused, forgotten and informal trails and also offering alternative modes of access such as climbing, jumping and sliding. The new connections are complex root-like structures which merge and intertwine with the vegetation, the topography, the culture, the community and the local history.