Building Post-Conflict

COACH - PROFESSORSHIP AT THE ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS, VIENNA

Design Studio IKA Academy of fine Arts, Vienna

Masters Summer Semester 2025

Students

Sophia Abendstein, Santiago Josemaria Anguita, Benjamin Baar

Priscilla Chick Kar Yi, Thomas Eder, Maximilian Gallo

Antonia Herbst, Kemi Houndegla, Moritz Tischendorf

GUESTS Final Reviews

Róisín Murphy / Architect, Artist & TV Presenter

Mark Hackett / Architect & Forum For Alternative Belfast

Isabella Forciniti / Franz Pomassl / Sound Artists

Rebecca Merlic / Thilo Folkerts / IKA

GUESTS Midterm Reviews

Franz Pomassl, Lars Fischer, Petra Hlaváčková, Nicole Sabella,

Rene Ziegler, Eva Sommeregger, Christopher Gruber

Sound and Body Workshop - Sofia Abendstein and Harold Stojan

Building Post-Conflict: Sound as a Medium for Architectural Transformation

In a world saturated with images, sound remains an overlooked yet profoundly powerful architectural medium. It shapes emotions, mediates conflict, and fosters connection in ways that visual forms alone cannot. The Building Post-Conflict design studio, part of the CMT Master’s program in the summer semester of 2025, sought to explore this neglected dimension, using Belfast—a city marked by centuries of colonial occupation, sectarian violence, and cultural resilience—as a living laboratory.

Belfast is a city of contradictions. It is scarred by towering "peace walls" that still divide communities, yet it is also a UNESCO City of Music, where punk’s rebellious roar and the melancholic strains of traditional folk have long served as both resistance and reconciliation. This studio asked: How can architecture engage with sound to foster healing in a post-conflict city? The answer lay not in grand gestures, but in subtle, resonant interventions—spaces that listen as much as they speak.

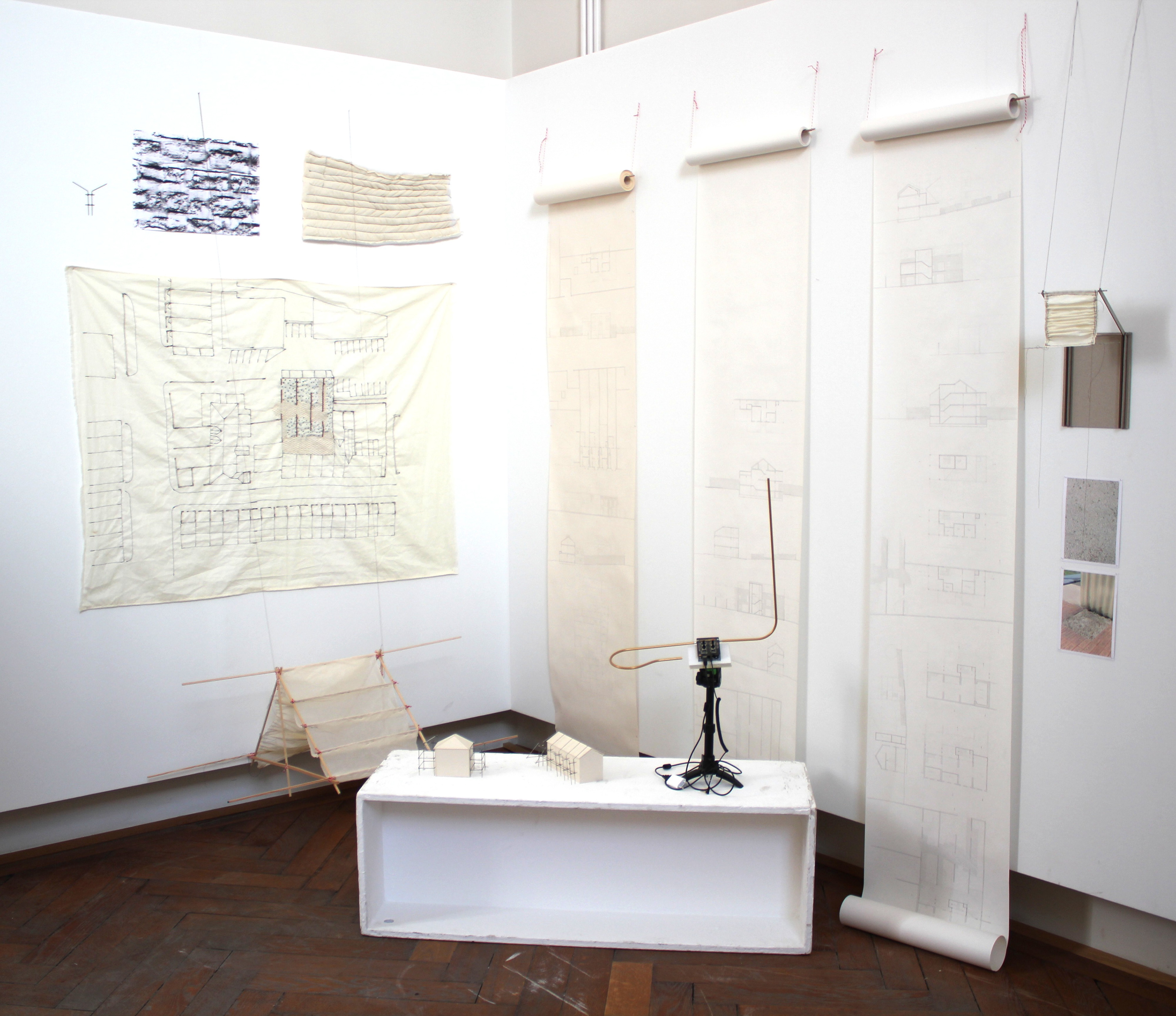

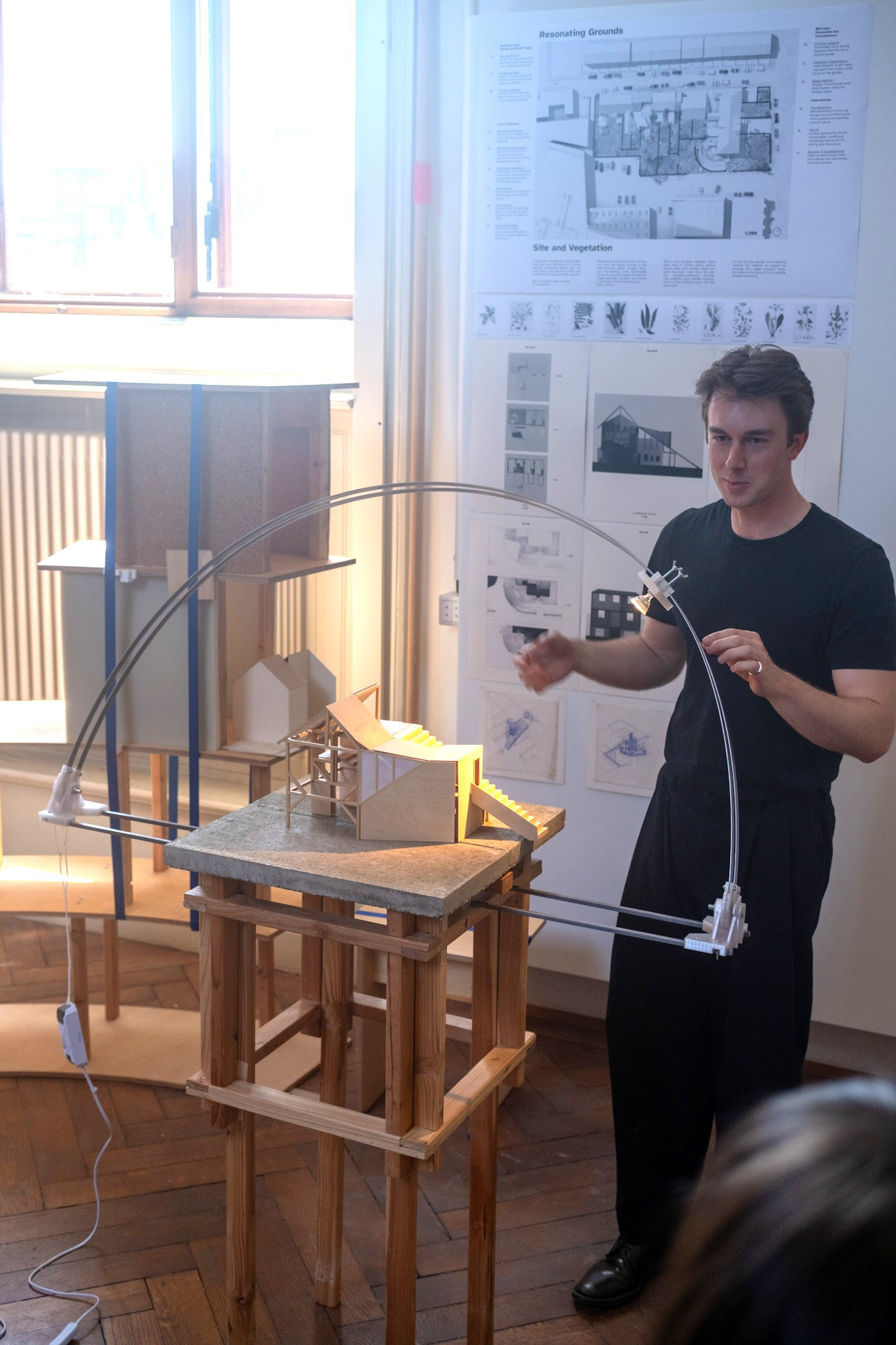

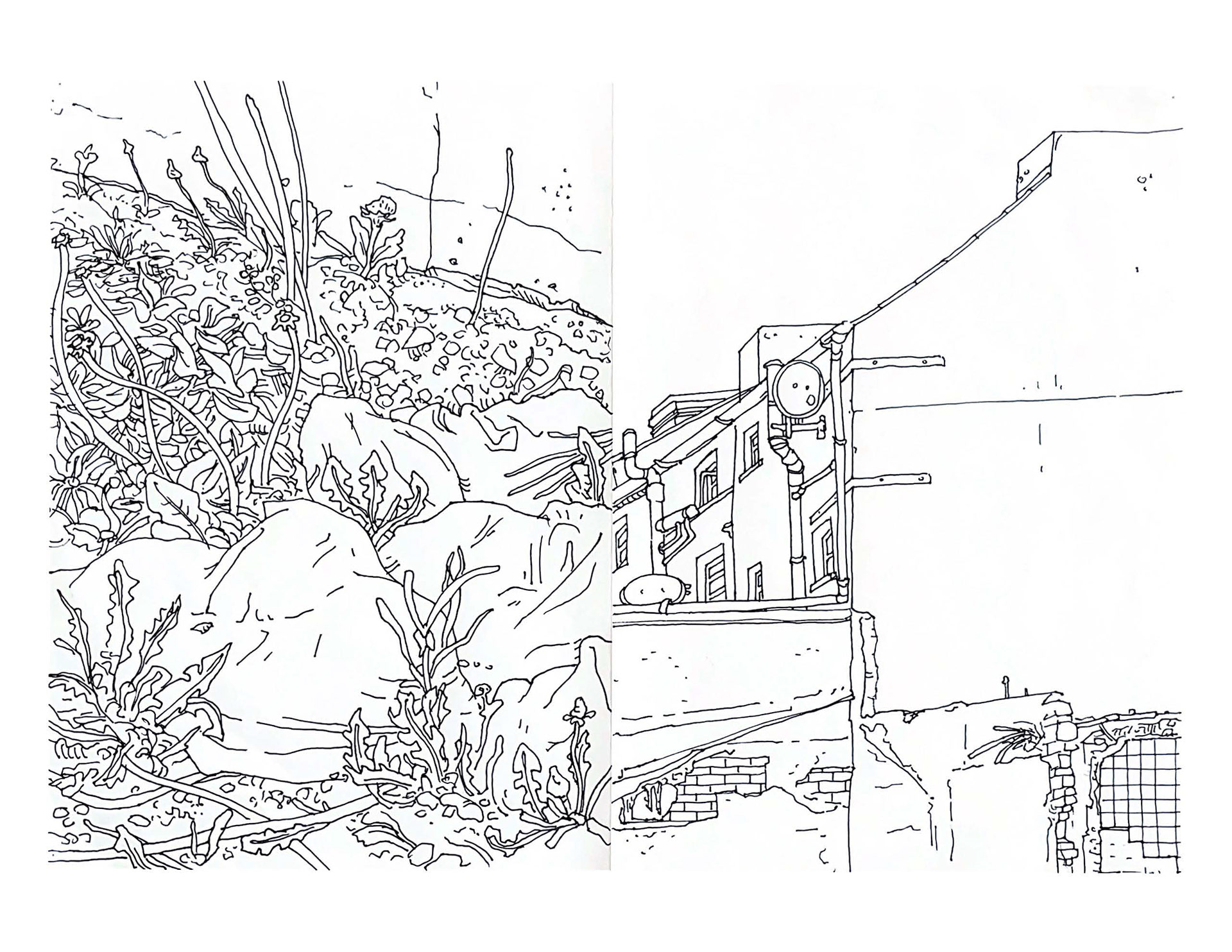

Our investigations took us beyond conventional architectural approaches. We studied acoustics, resonance, and vibration as spatial forces, visiting Lametta, a sound studio specializing in film and theatre, where we learned how soundscapes shape narrative and emotion. At the University of Vienna, we entered an anechoic chamber—a space so silent it revealed the body’s own sonic presence, a humbling reminder of how deeply sound is tied to our perception of space. In a growl workshop led by artist and performer Harald Stojan, we explored how the voice interacts with architecture, discovering how even the most primal sounds can transform spatial experience.

Most crucially, we travelled to Belfast, immersing ourselves in its layered soundscape. The city’s divisions were palpable—the barbed wire, the murals, the uneasy silences in certain neighbourhoods. Yet, everywhere we went, we encountered people using music, poetry, and song to bridge divides. It seemed that no matter their profession—harpist, architect, orchestra director, poet, or punk musician—everyone was an activist, a storyteller, and often, a fluent Irish speaker. Their work demonstrated how sound can reclaim space, rewrite narratives, and resist erasure.

The Ulster Orchestra play Metamorphosen by Richard Strauss

in their rehearsal rooms (tweaked) in a former Presbyterian Church

Sound as an Architectural Medium

Architecture has long been dominated by the visual—form, light, materiality—while sound is treated as an afterthought, something to be controlled rather than designed. Yet sound is inherently spatial. Unlike vision, which is directional, sound envelops us, bypasses walls, and lingers in memory. In Belfast, where political and religious divisions are etched into the urban fabric, sound offers a way to transgress boundaries, to create shared experiences where physical barriers persist.

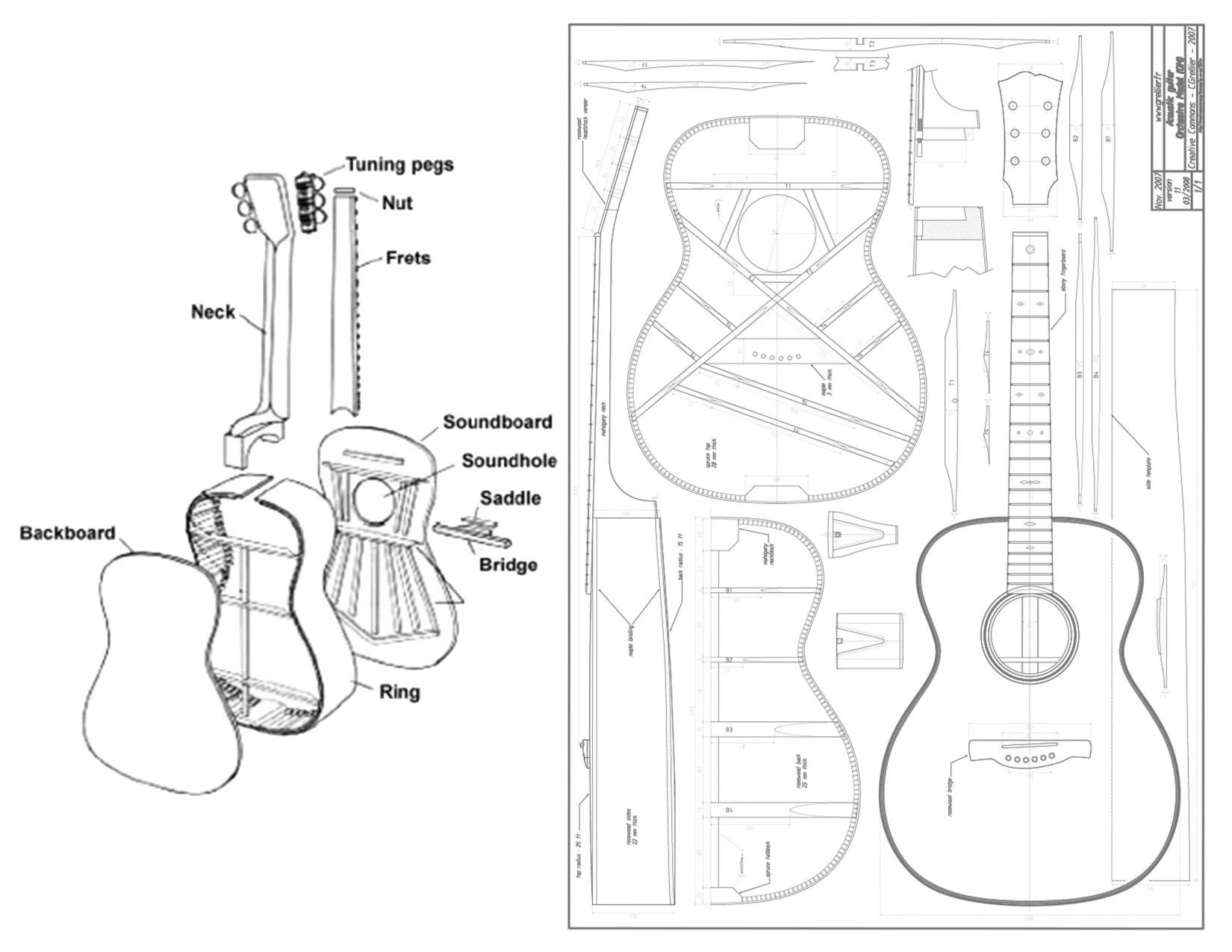

The studio’s framework was built on three key ideas. First, that sound is not merely an accessory to architecture, but a medium that can shape space as powerfully as walls or light. Second, that music in Belfast is inherently political—whether punk’s defiance or folk’s lament, it carries the weight of history. Third, that architecture itself can become an instrument, modulating sound to foster connection or contemplation.

Students were tasked with designing interventions on three charged brownfield sites, each bearing traces of Belfast’s industrial, political, and cultural history. These were not blank slates, but palimpsests of conflict and community. The challenge was to engage with sound not just as an aesthetic element, but as a tool for spatial and social transformation.

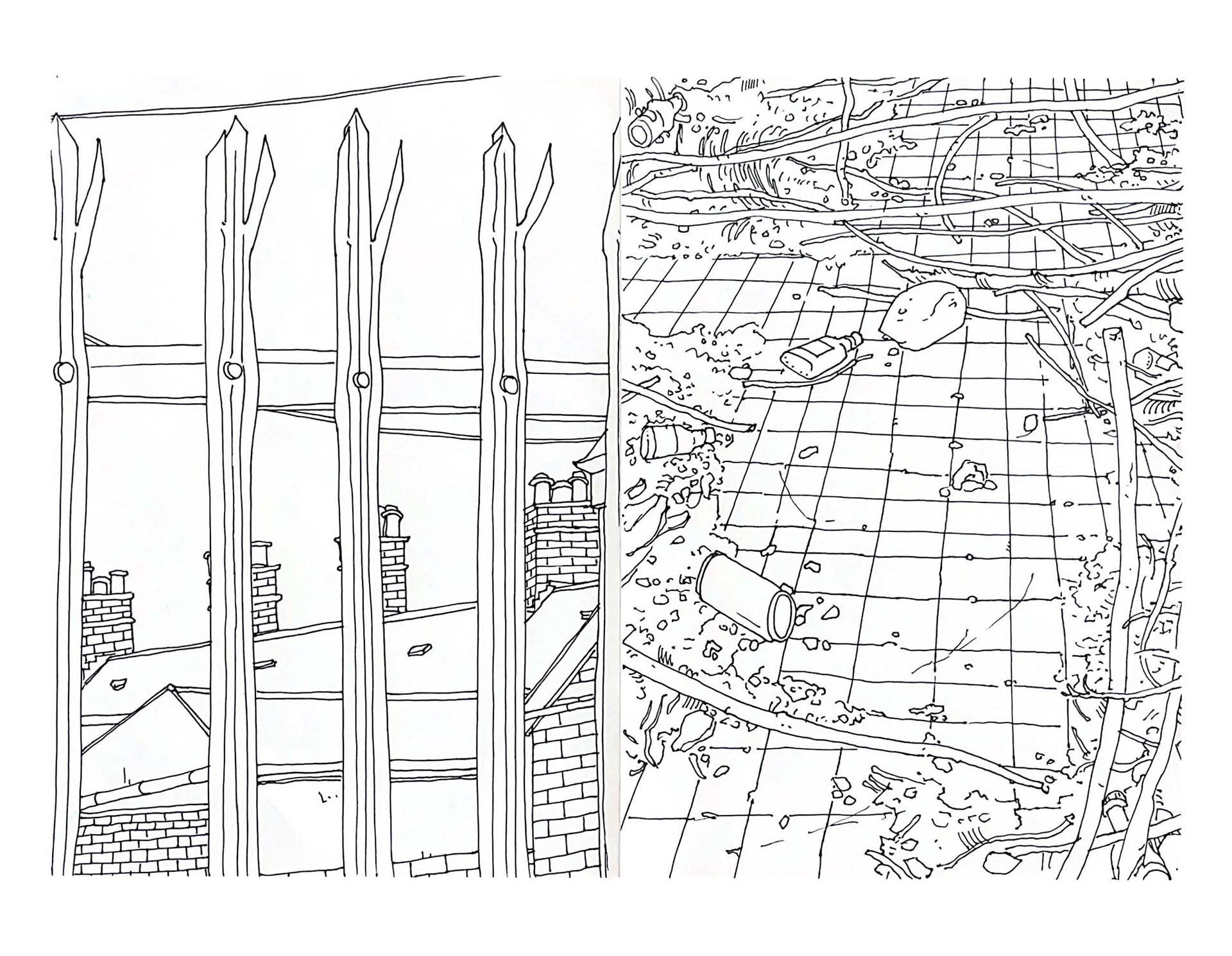

So-called Peace Gates, where, even today nearly 30 years after the signing of the peace agreement, the gates are closed at night to separate a predominantly protestant from a predominantly catholic neighbourhood

Resonant Interventions: Weaving Sound into the Urban Fabric

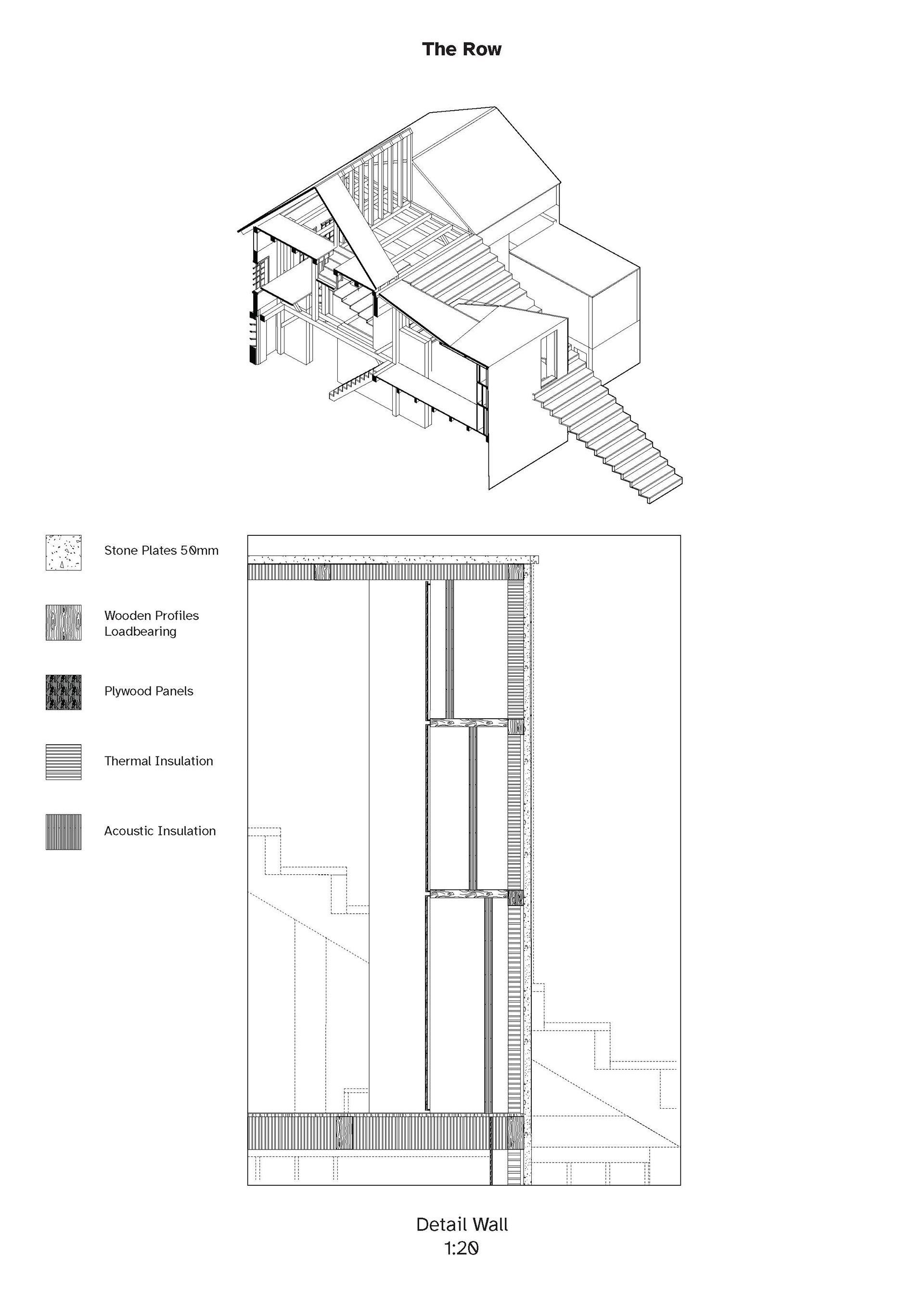

The students’ projects collectively explored how sound could reanimate Belfast’s fractured landscapes. One approach was adaptive reuse, where derelict structures were reimagined as resonant spaces. A row of crumbling brick terraces, once emblematic of working-class Belfast, became a living soundscape—a year-long residency for jazz and folk musicians, their back gardens transformed into a shared courtyard under a translucent canopy. The design embraced decay rather than erasing it, stabilizing the structures while retaining their raw character, allowing music to breathe new life into neglected urban fabric. (Sofia Abendstein – Resonant Renewal: Transforming Belfast’s Terraces into a Living Soundscape)

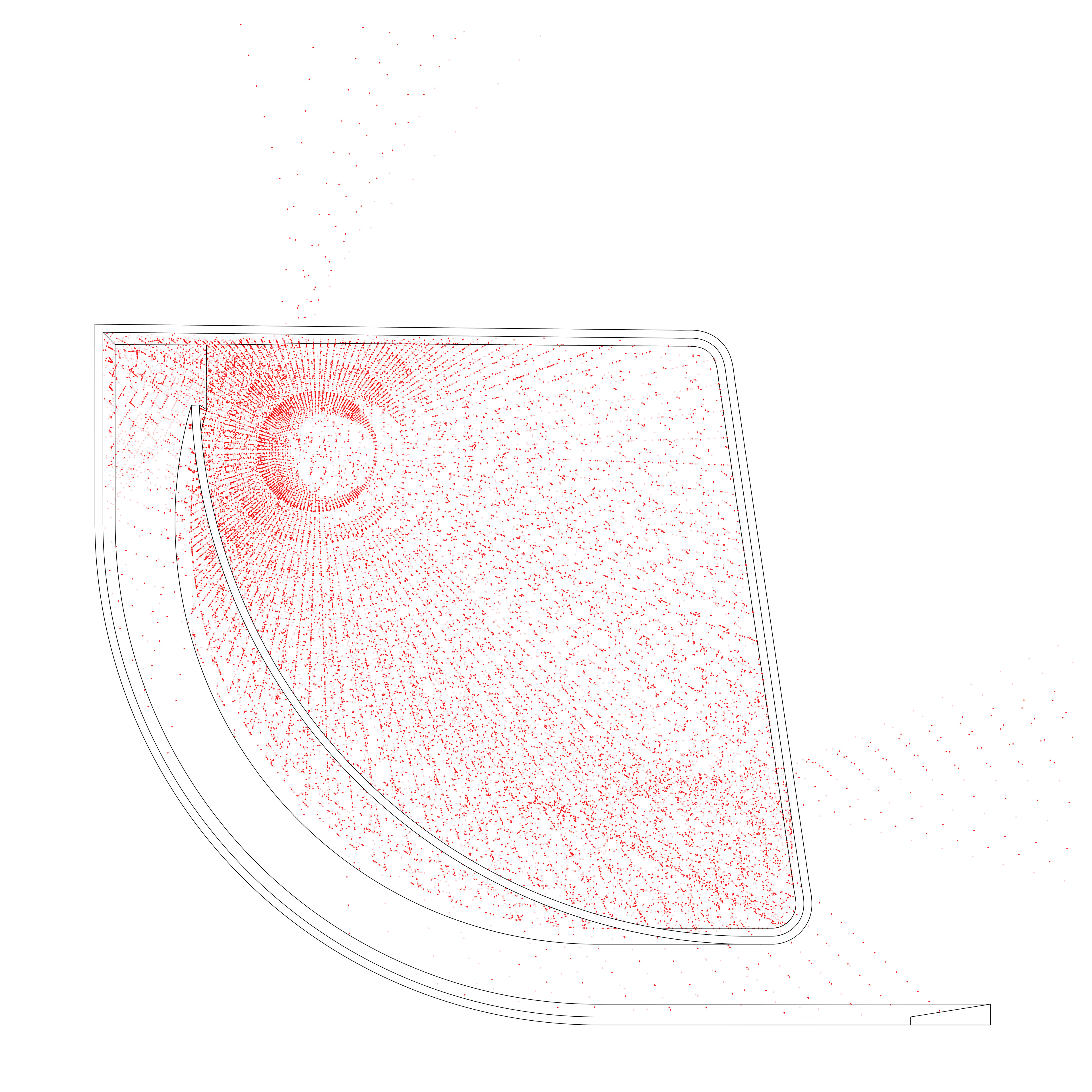

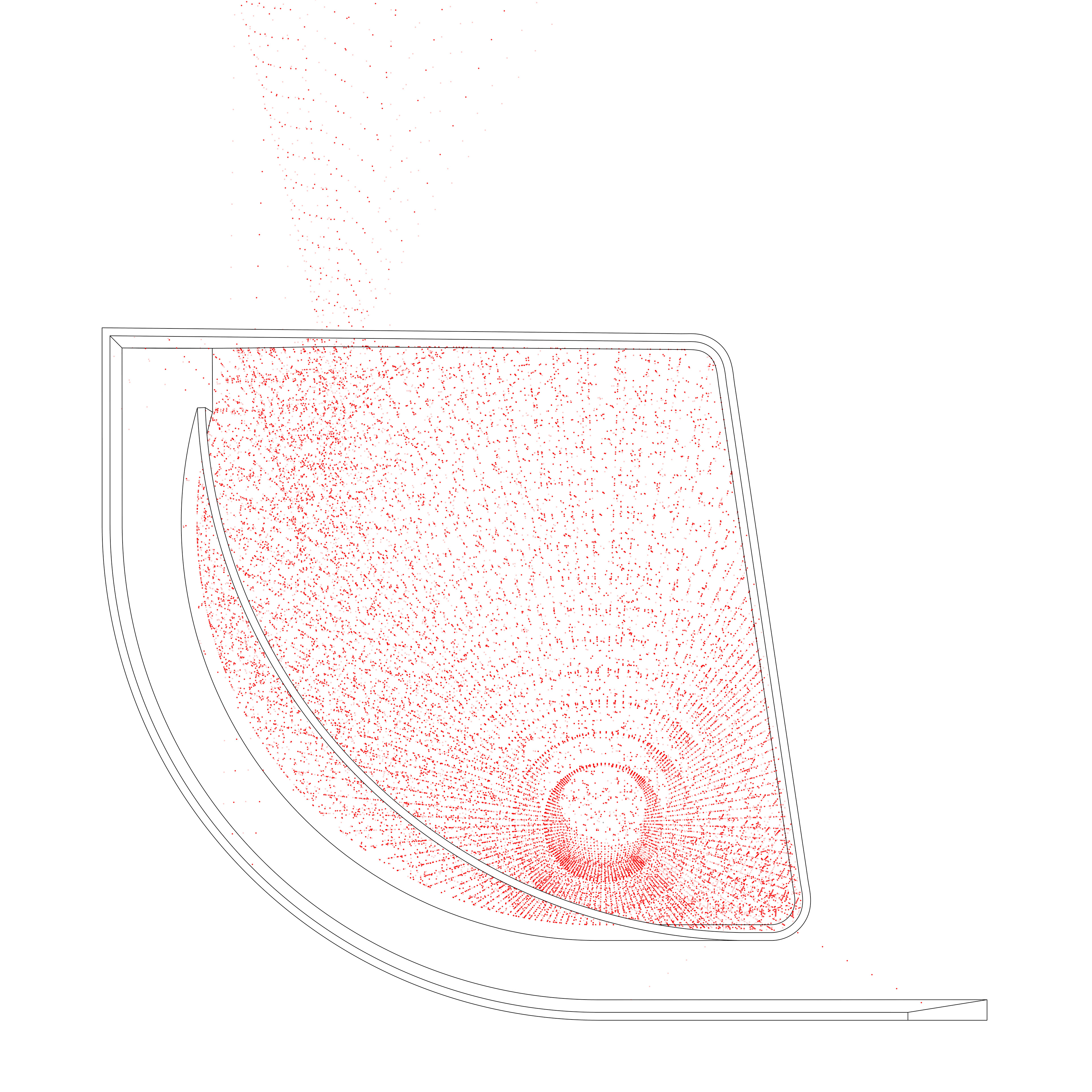

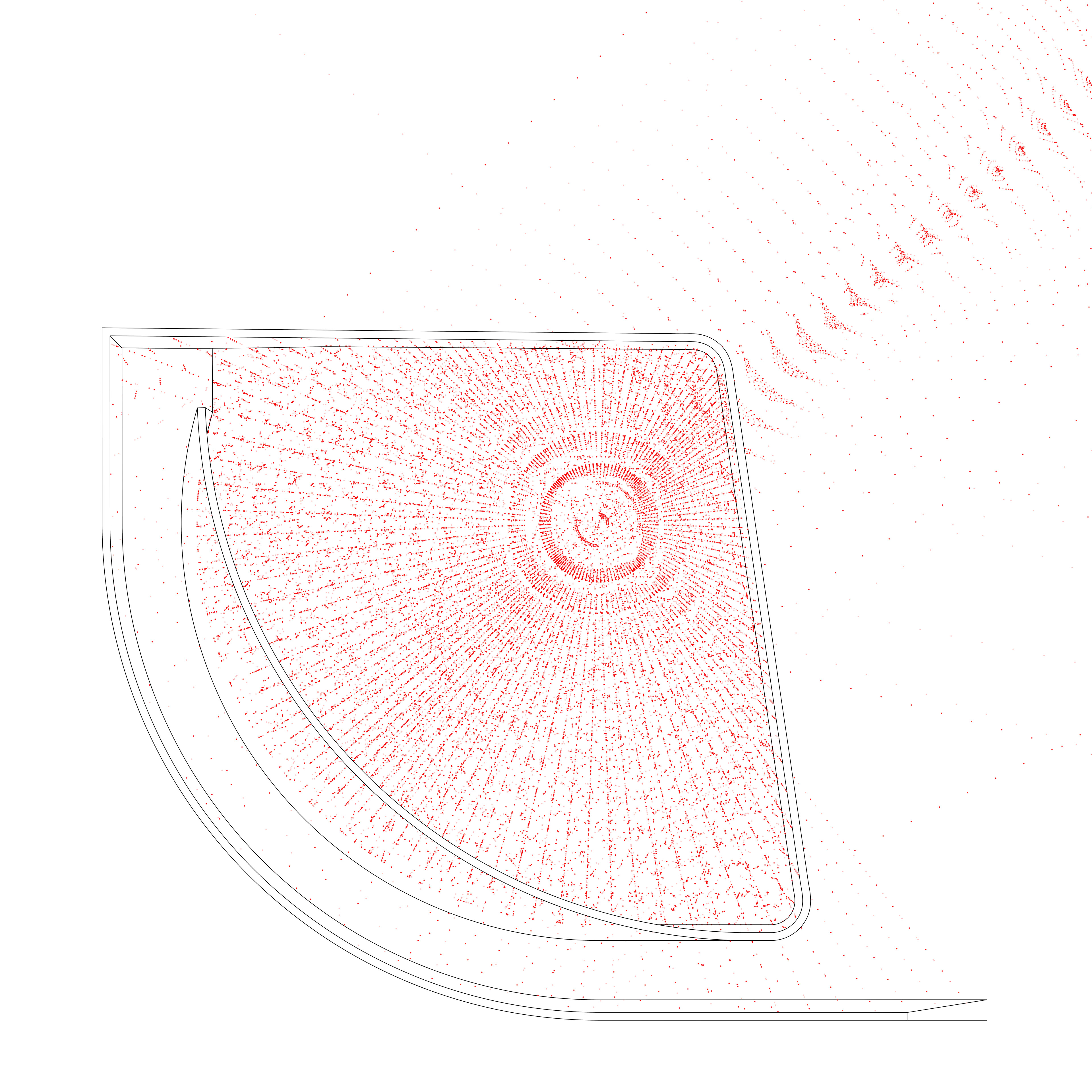

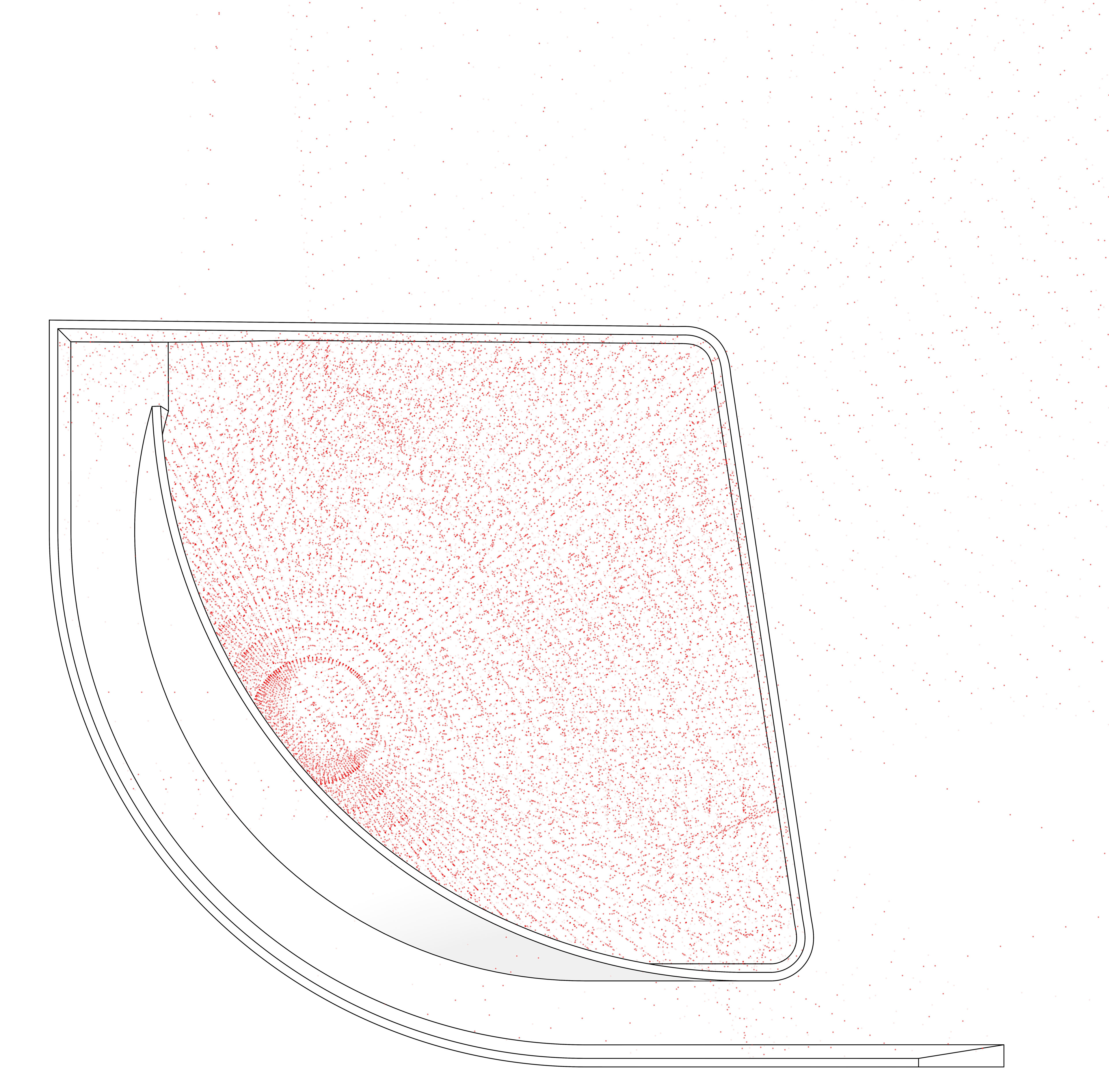

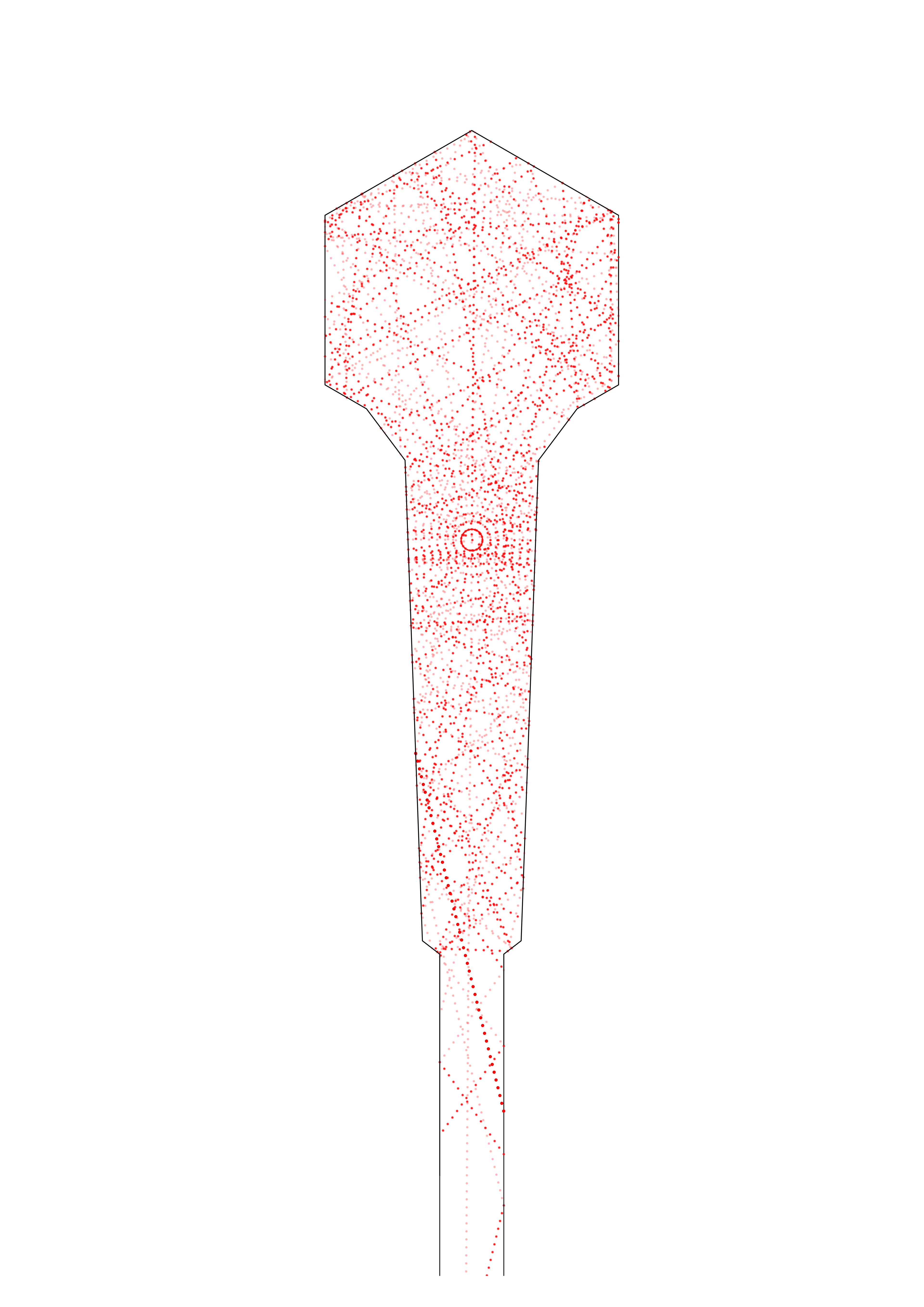

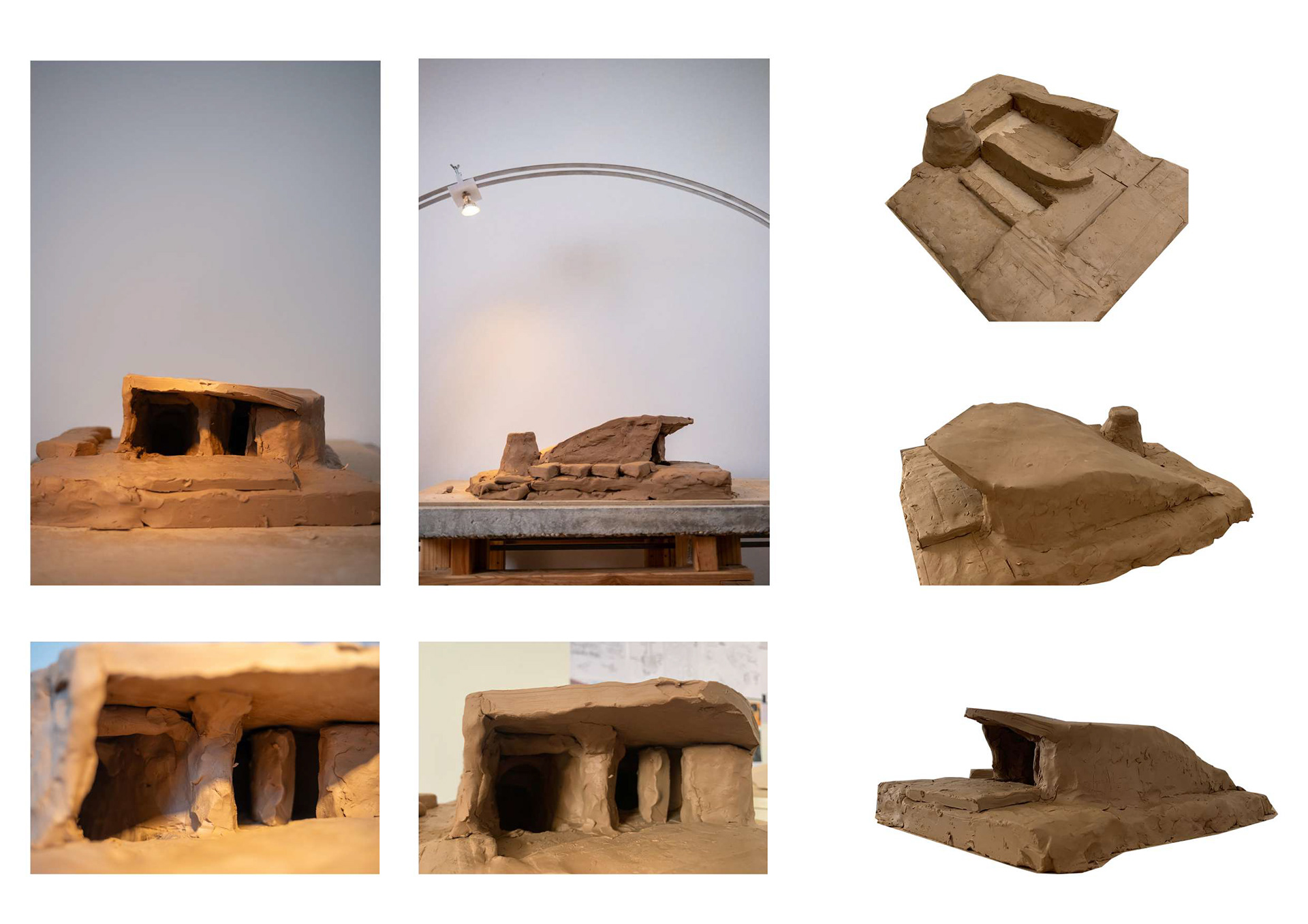

Another project drew inspiration from Neolithic ritual sites, where architecture and acoustics fostered communal bonds. A spiralling rammed earth wall formed an open-air venue, while a subterranean chamber, tuned to an infrasonic frequency, induced a visceral, wordless connection among visitors. Aeolian pipes responded to the wind, filling the space with shifting harmonies—an architecture that avoided overt symbolism, instead using sound as a neutral ground for shared experience. (Benjamin Baar – RREVERB: Sonic Architecture as a Medium for Post-Conflict Healing)

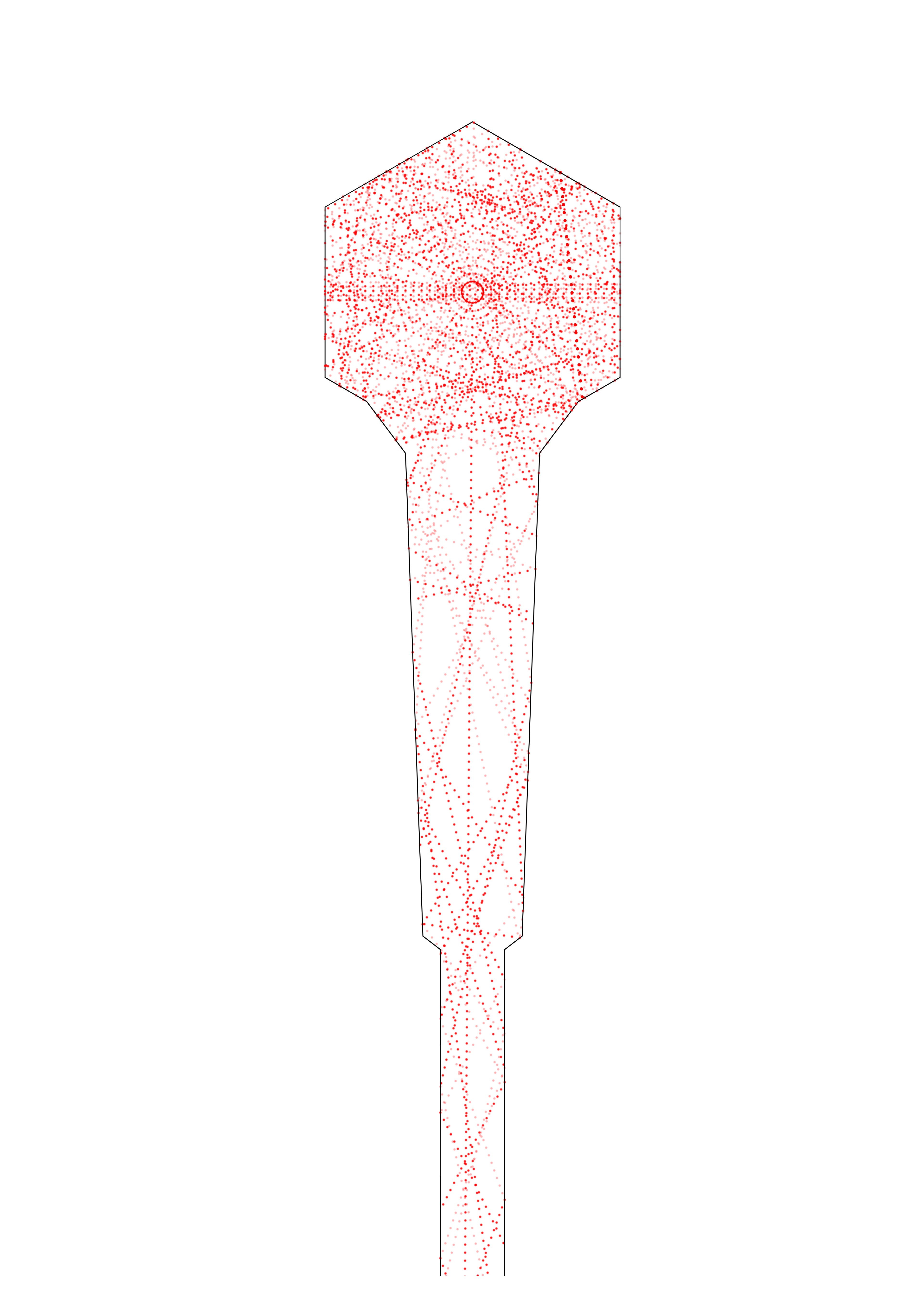

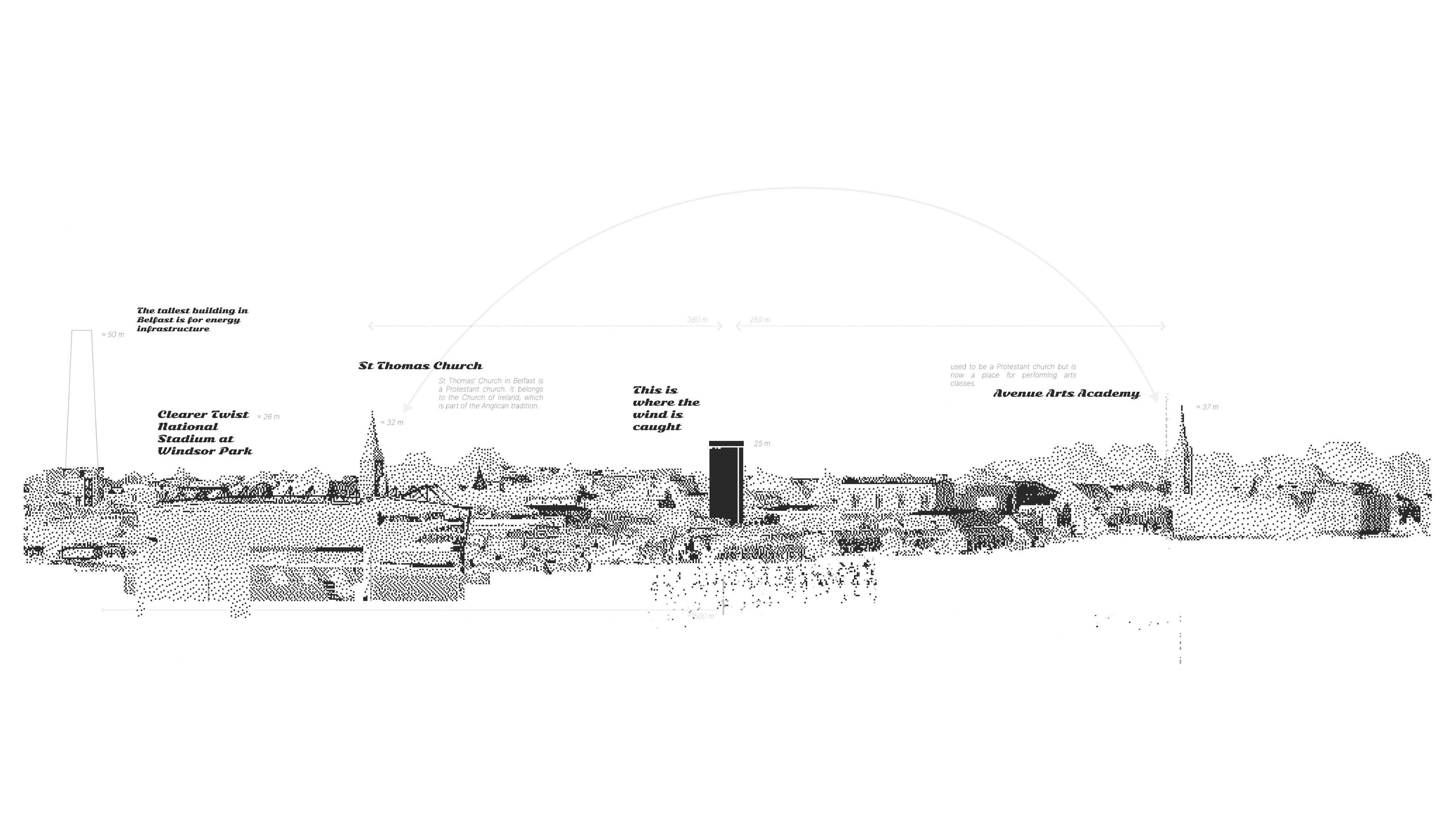

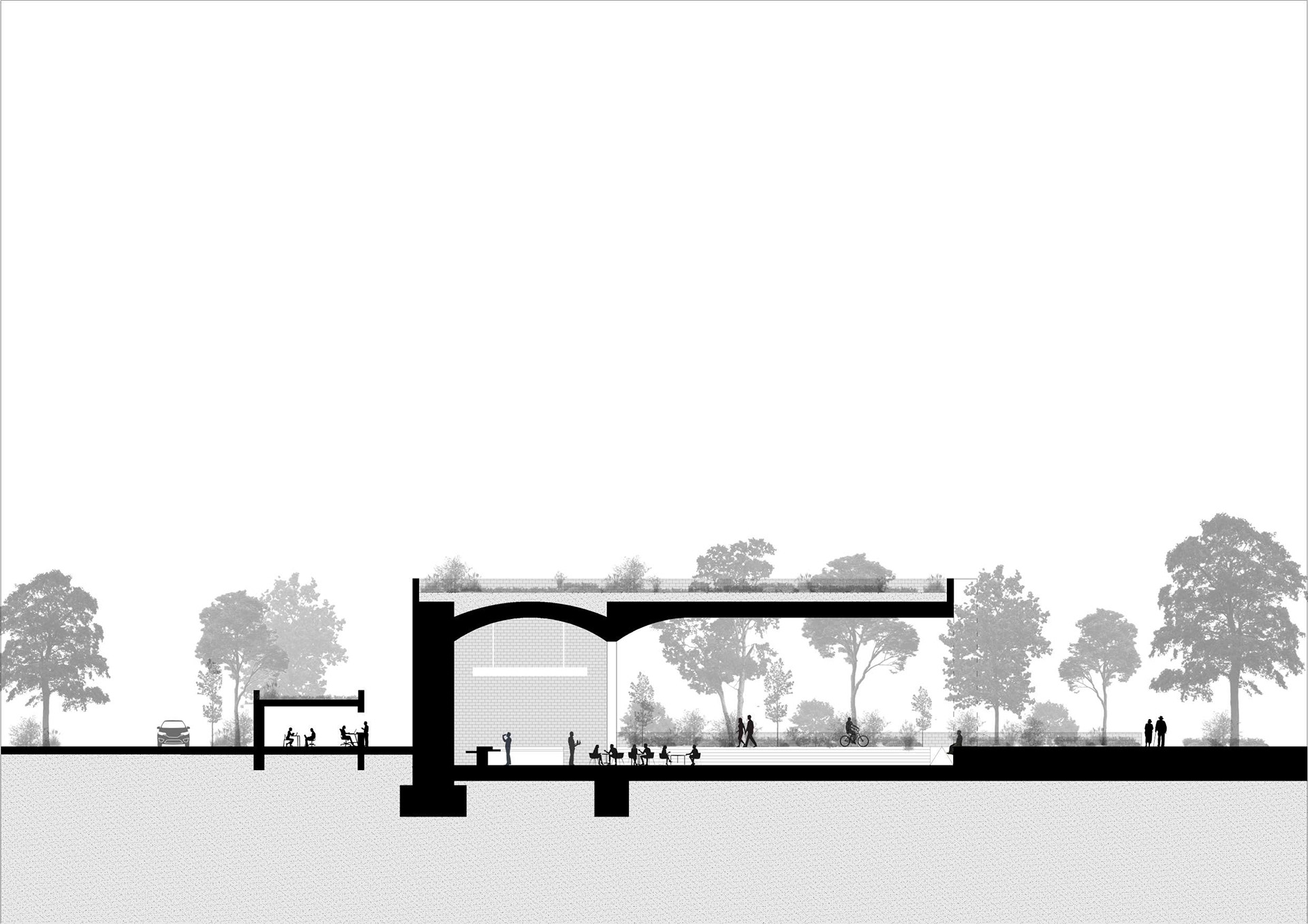

Elsewhere, the challenge was to disrupt the acoustic dominance of churches and stadiums, institutions that have long shaped Belfast’s sonic landscape. One proposal turned architecture itself into an instrument, with wind-activated turbines producing a slow drone—evoking the communal call of church bells, but secular, open to all. The venue’s upper level, exposed to the elements, amplified the dialogue between wind, sound, and performance, creating a dynamic space for spoken word and music that resisted institutional control. (Thomas Eder – Where the Wind Sings: A Resonant Hub for Community and Performance)

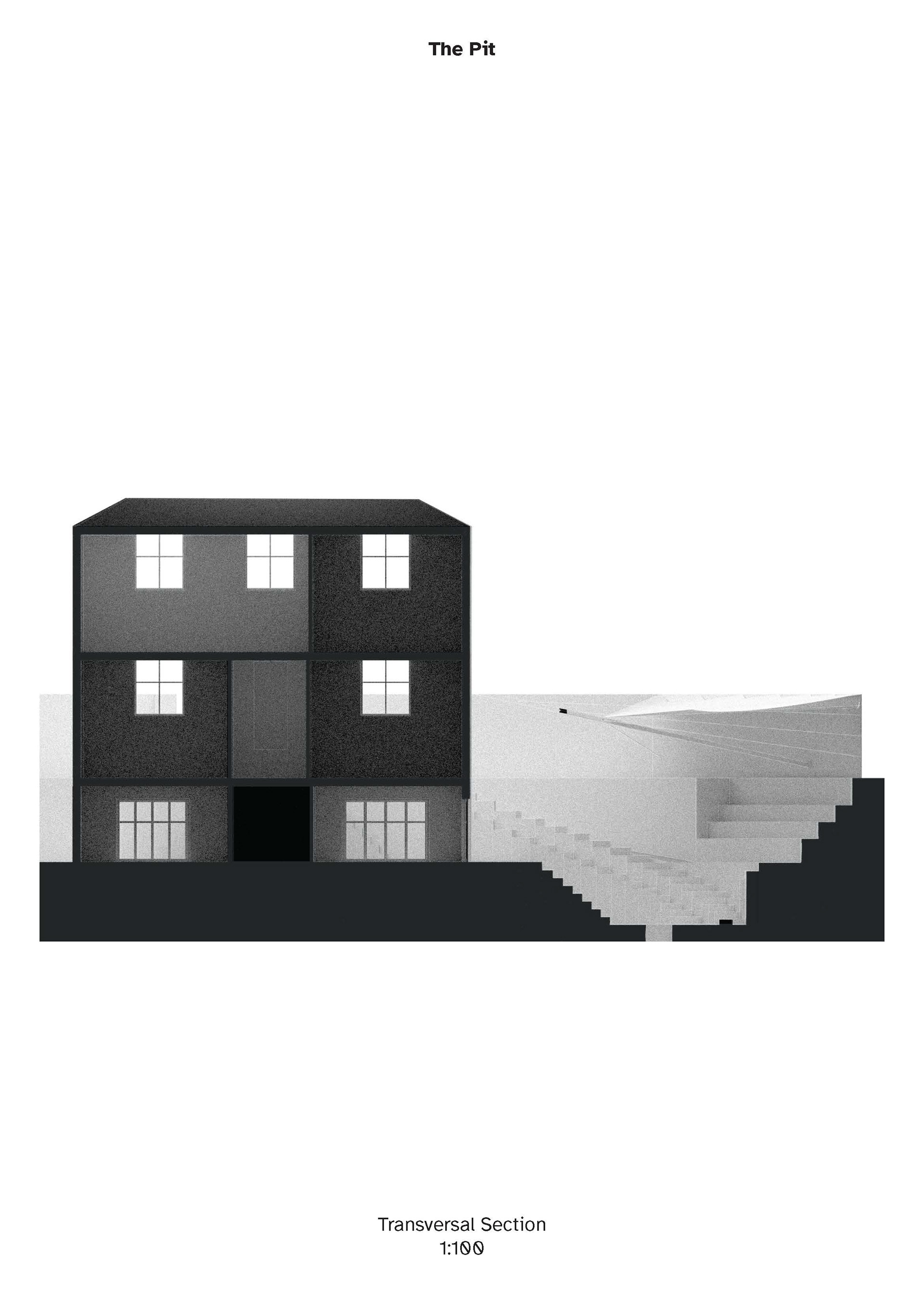

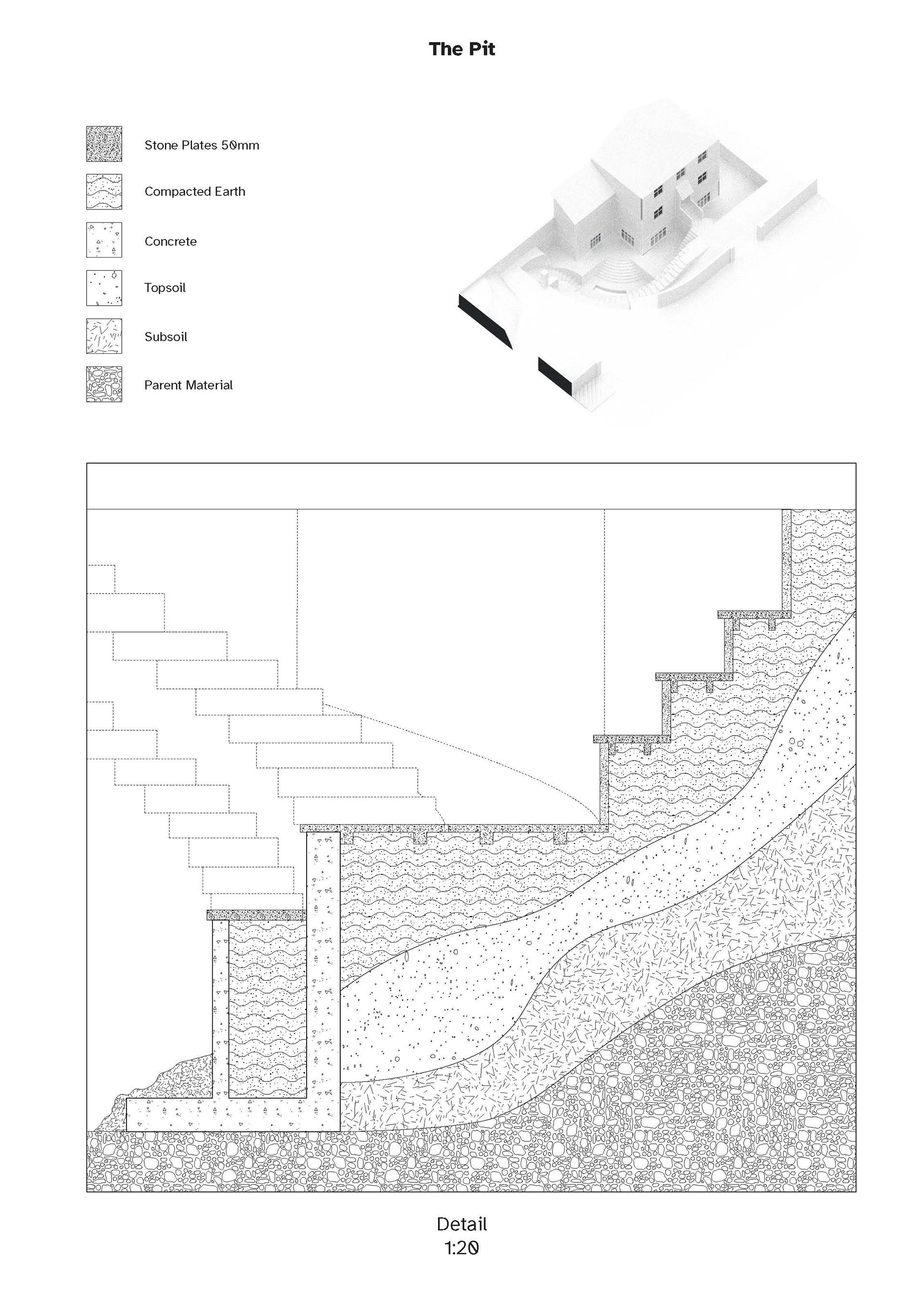

Sound was also explored as an ecological force. A hybrid intervention merged terraced houses with a rewilded garden, where a sunken chamber provided a space for deep listening, and thickened walls modulated acoustics for performances. The rooftop terrace extended the soundscape upward, blurring boundaries between architecture and landscape, framing sound as part of an evolving ecosystem rather than a static event. (Maximilian Gallo – Resonating Grounds: Acoustic Ecology and Collective Memory in Belfast’s Post-Conflict Landscape)

In a more urban context, a neglected street was reimagined as an interactive soundwalk, where sculptural installations amplified natural and constructed sounds. Repurposed bell and dome structures created auditory feedback loops, turning the street into a shared instrument. This challenged the passive movement typical of cities, asking: How can a site reveal itself through sound? The answer lay in encouraging active listening, in making the act of hearing a participatory, spatial experience. (Kemi Houndegla – Resonant Pathways: A Sonic Exploration of Woodvale)

Sound and Social Repair

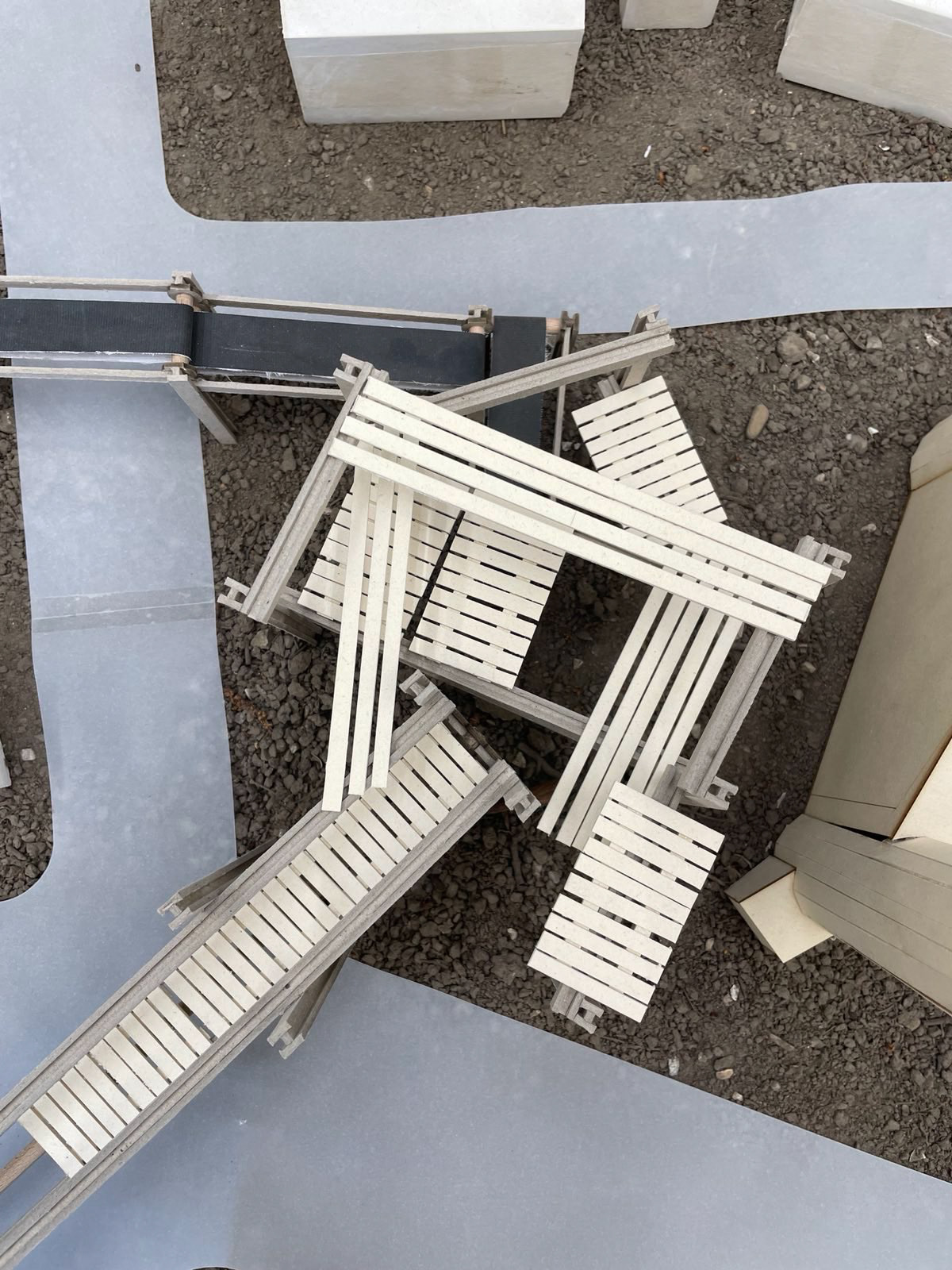

The most compelling aspect of these projects was their engagement with sound as a tool for social repair. In a city where physical barriers still divide communities, architecture that prioritizes listening can create spaces of encounter. One proposal revived Belfast’s lost tradition of Dancing on the Crossroads, with a lightweight timber pavilion whose foldable walls allowed performances to spill into the street. Wireless speakers extended the experience anonymously, creating a collective auditory moment without requiring direct interaction—a subtle but powerful way to bridge divides. (Antonia Herbst – Soundbox: A Resonant Pavilion for Music and Reconciliation in Belfast)

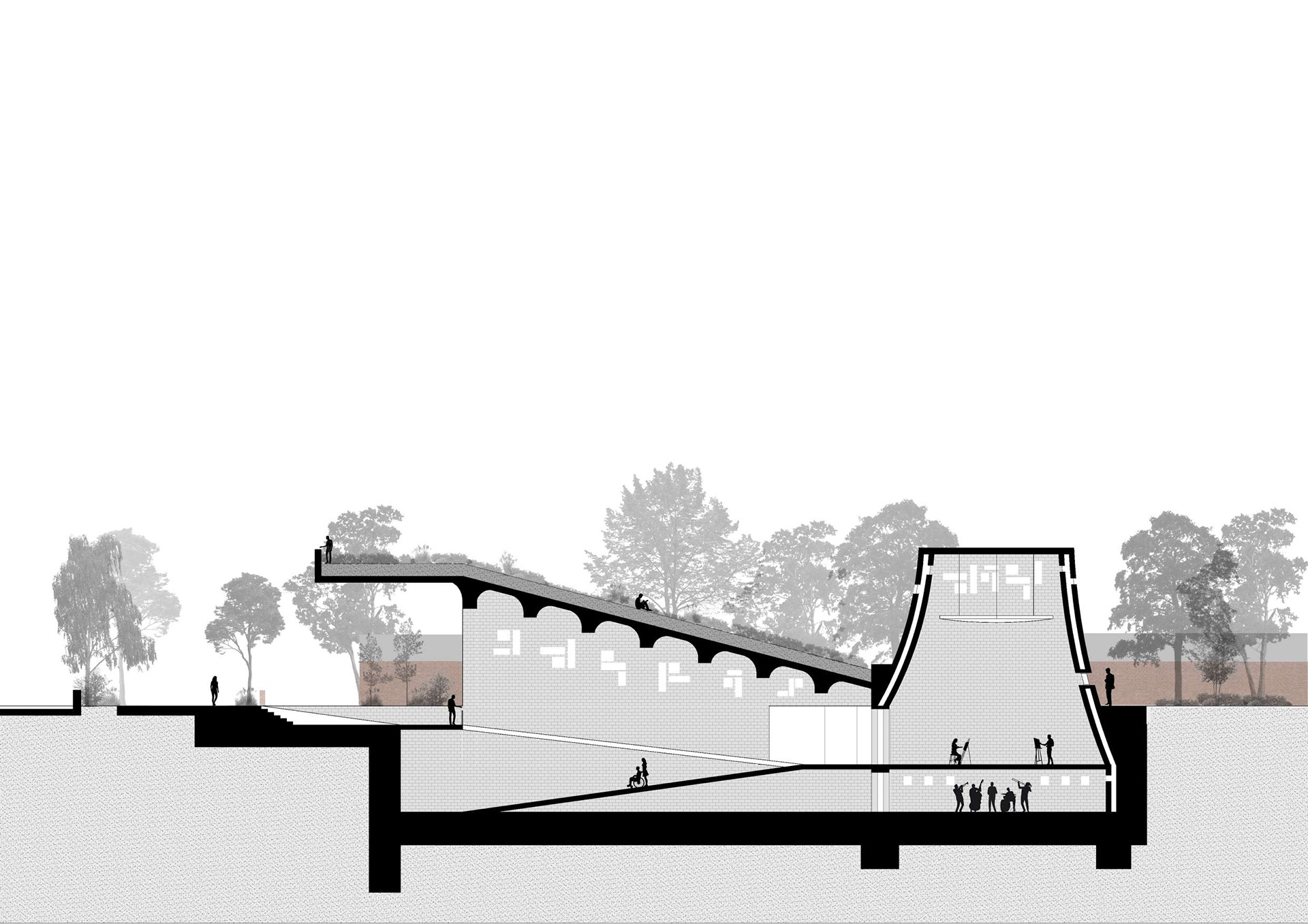

One project reimagined a neglected urban edge as a hybrid soundscape, where a sunken plaza—carved into Belfast’s glacial topography—became an intimate venue for string performances, its earthen walls modulating acoustics like a natural instrument. Above, an undulating parkland of repurposed cobblestones and wild greenery blurred the line between infrastructure and landscape, while a brick-clad workshop pavilion anchored the site in communal making. By weaving together excavation, music, and ecological renewal, the design transformed a peripheral space into a resonant threshold, where the city’s layered histories could be heard anew. (Santiago Josemaria Anguita – Reshaping Belfast’s Edge: A Hybrid Landscape for Music, Community, and Urban Renewal)

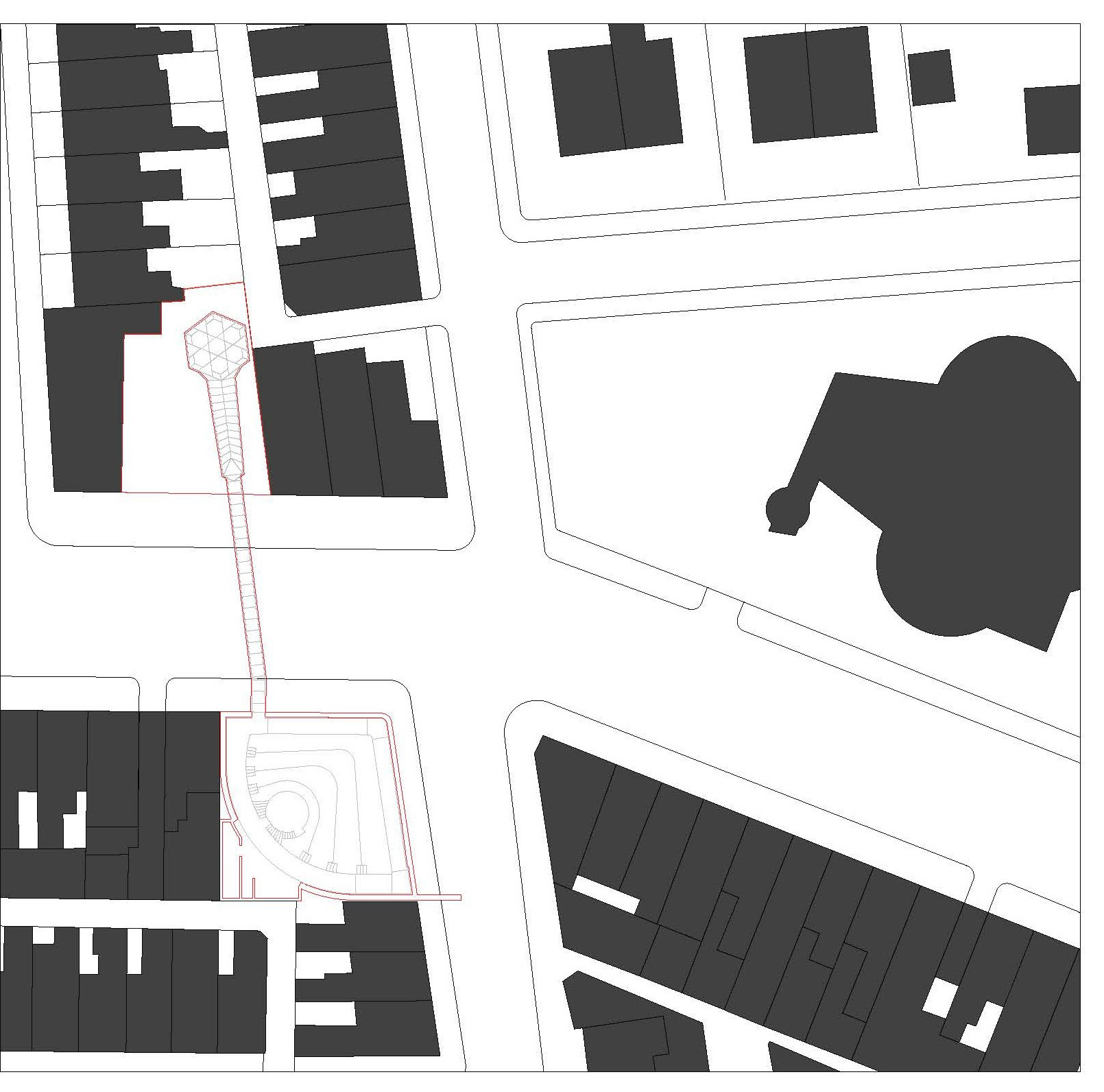

Another design, inspired by Quaker traditions of silent listening, wove a double-spiral plaza through key community anchors. Hollow pipes responded to wind, turning architecture into an instrument, while tiered elevations and playscapes invited exploration. The project prioritized active listening as a civic ethos, creating a space where generations and faiths could intersect without the pressure of dialogue—sometimes, simply sharing sound is enough. (Priscilla Chick Kar Yi – Resonant Connections: A Civic Landscape for Dialogue and Listening in Belfast)

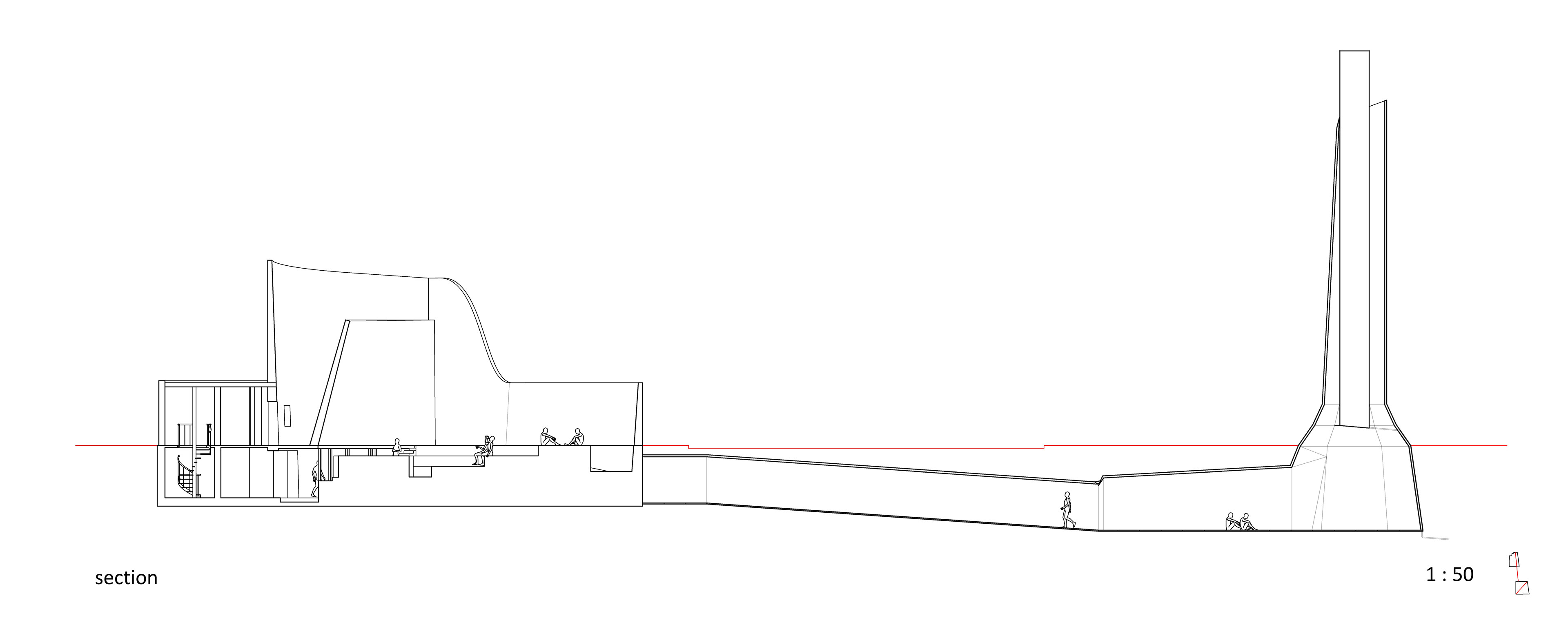

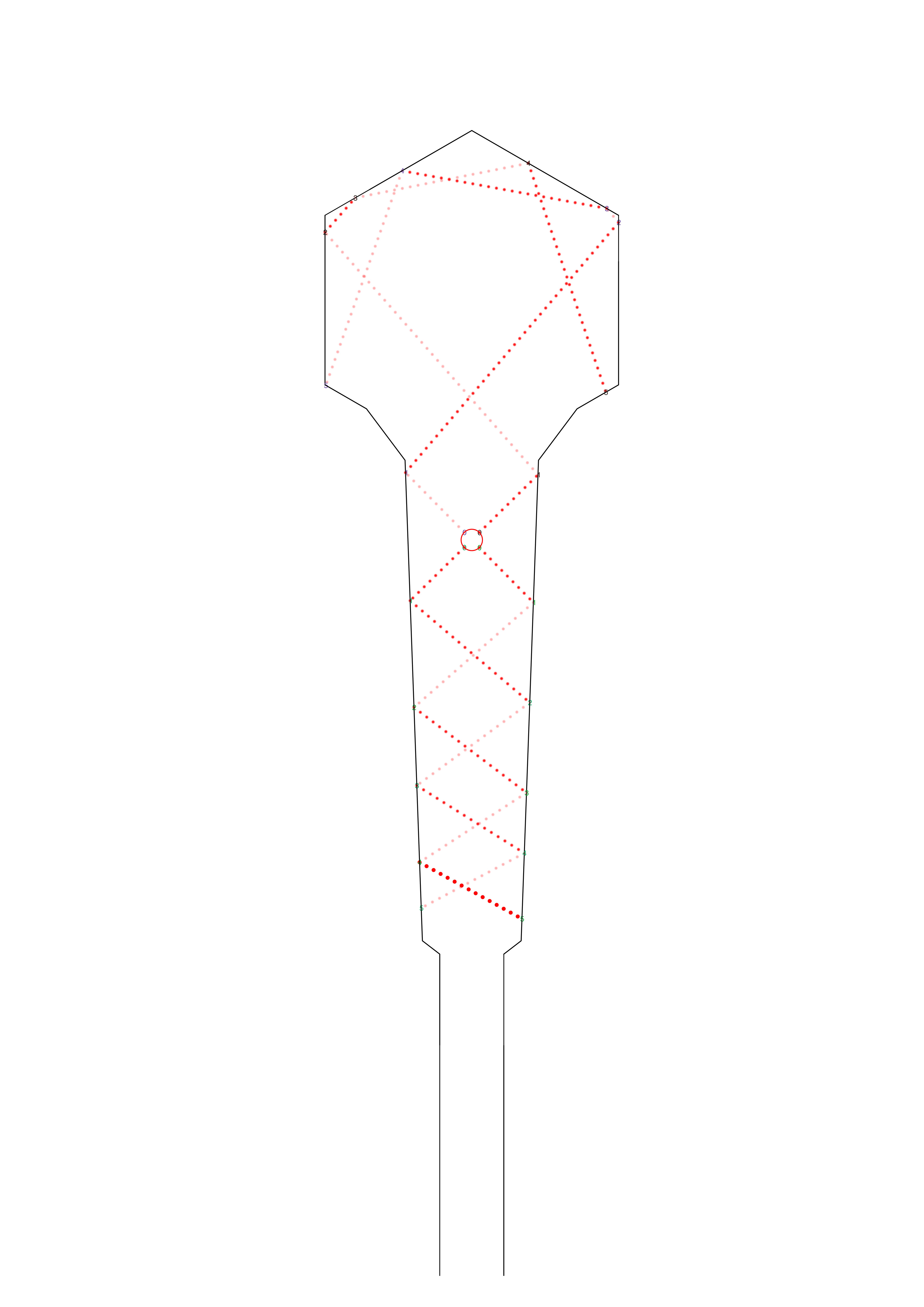

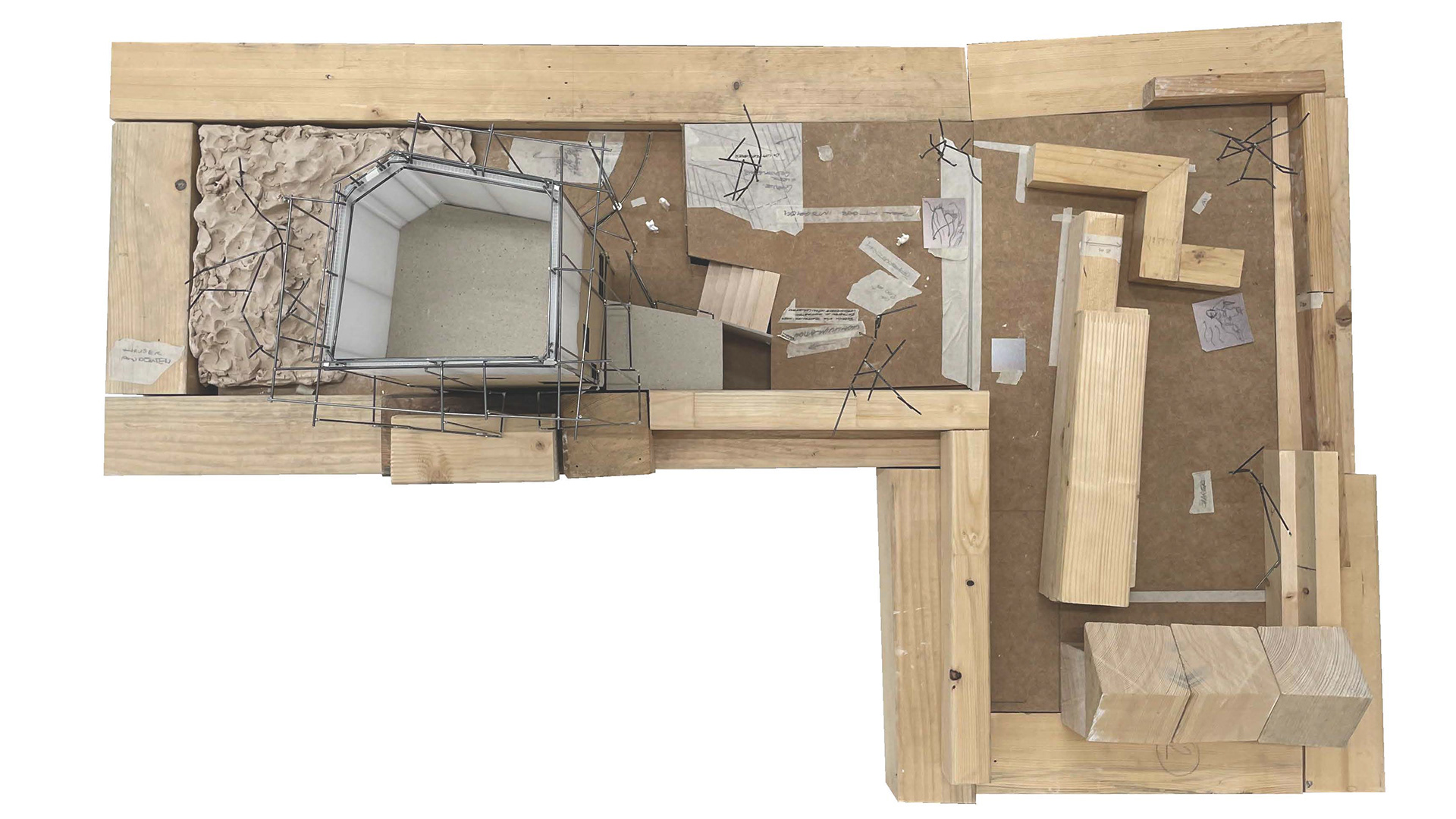

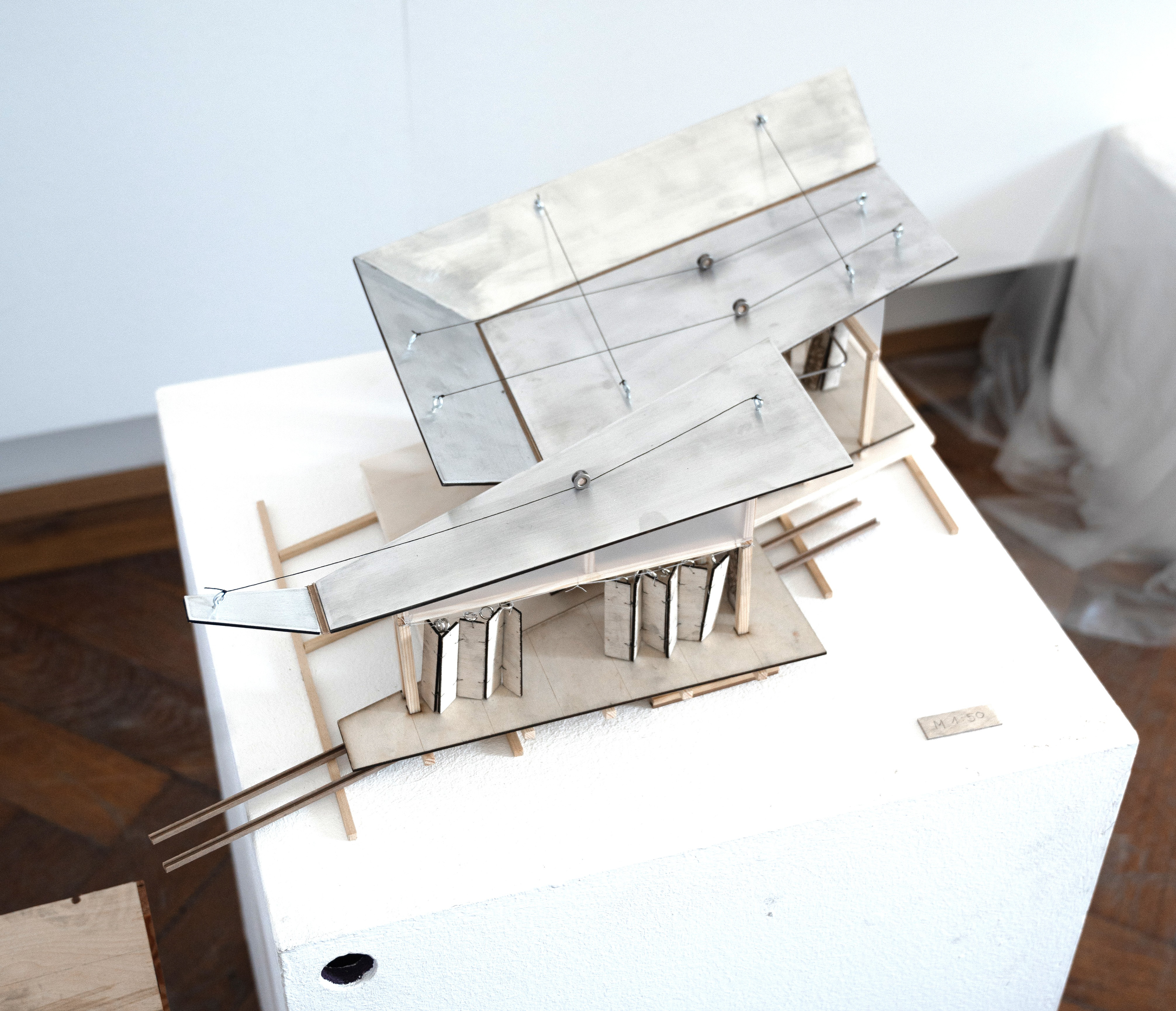

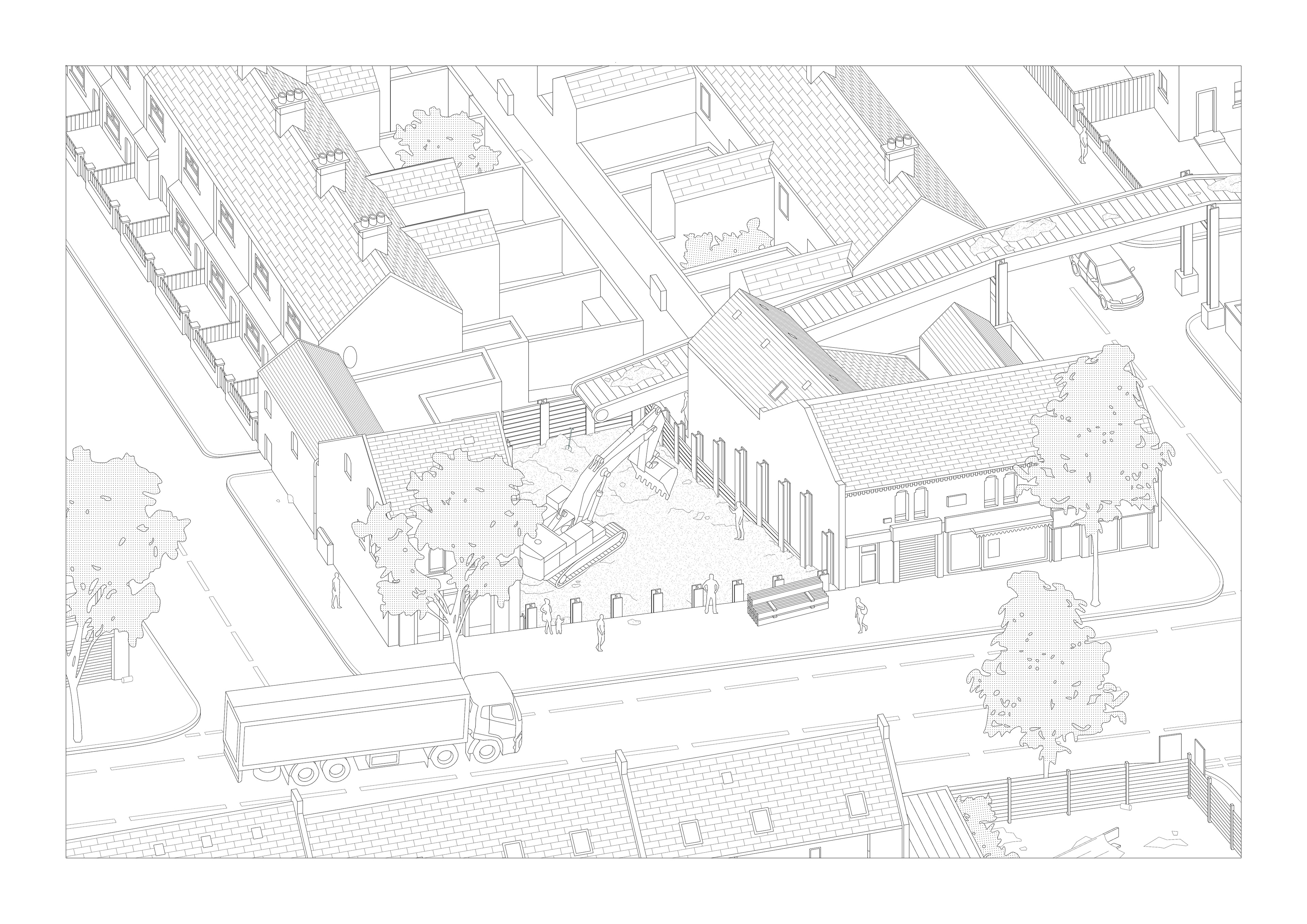

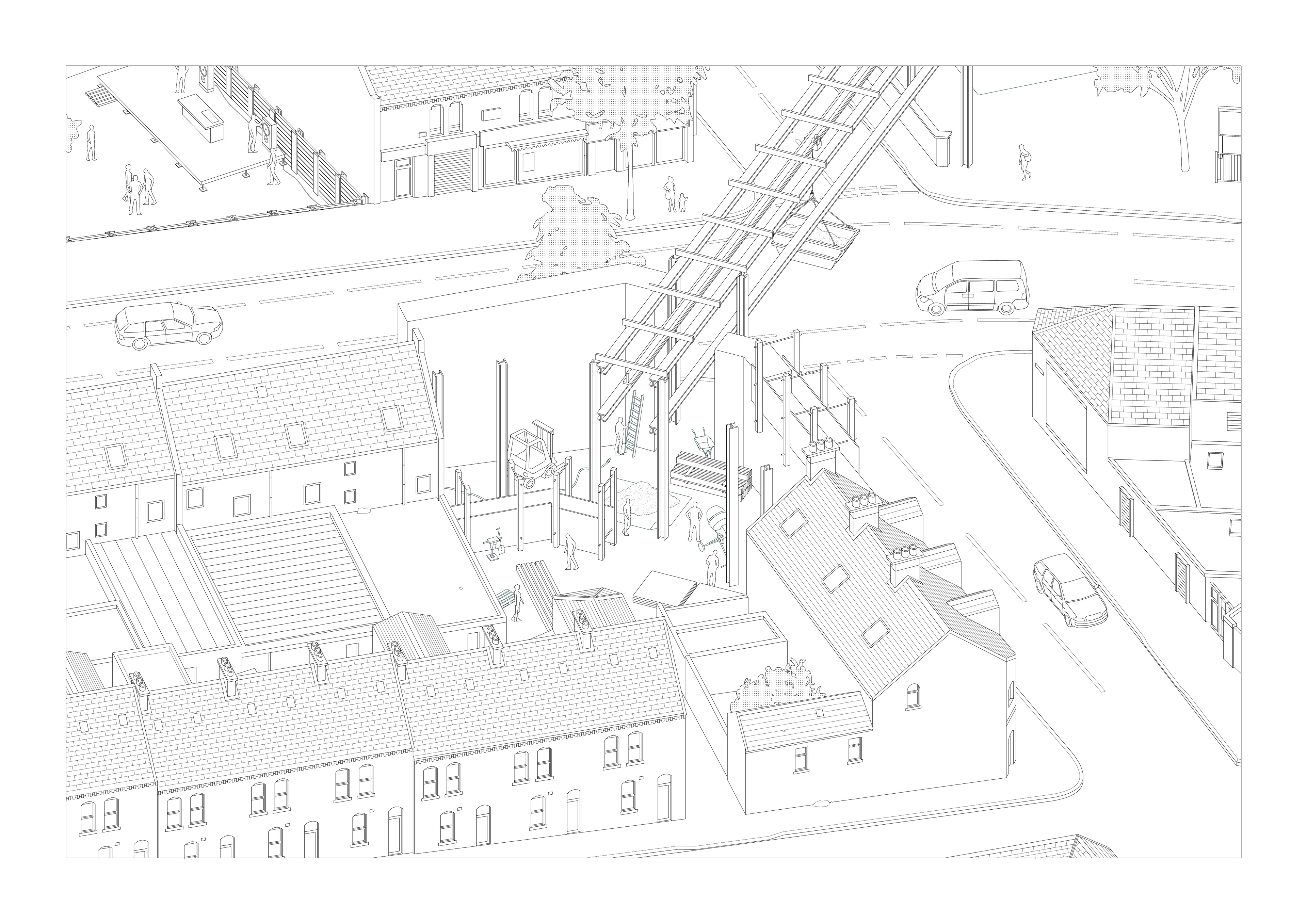

Perhaps the most radical approach treated construction itself as a resonant act. One project framed building as a synthesizer—excavation as input, rammed earth as output—with a crane bridging the road as both functional tool and symbolic connector. The community was engaged in material transformation, making architecture itself a participatory instrument. This challenged the notion of a finished, static building, proposing instead an evolving, resonant system where process and outcome were equally important. (Moritz Tischendorf – Synthesizing Architecture: A Sonic and Participatory Approach to Belfast’s Music Centre)

Conclusion: Listening as an Architectural Act

The Building Post-Conflict studio revealed sound as a potent, underutilized force in architecture—one capable of shaping memory, mediating conflict, and fostering collective experience. In Belfast, we saw how music and voice could reclaim space, even in the shadow of division. The students’ projects demonstrated that architecture need not be static or silent. It can hum, resonate, and amplify. It can be an instrument, a mediator, a listener.

As the world grapples with escalating conflicts, the lessons of this studio resonate beyond Belfast. If architecture is to contribute to peace, it must learn to listen. Sound, so often ignored, may be one of its most powerful tools. In a post-conflict city—or any divided society—the act of listening is radical. It requires humility, patience, and a willingness to hear what is not being said. The projects emerging from this studio suggest that architecture, when attuned to sound, can do more than house people—it can help heal them.